Naturalistic Intervention

Naturalistic Intervention involves a sequence of strategies designed to identify the contexts for intervention, provide training to the early intervention team members including providers and parents, arrange the environment to elicit the target behavior, and then elicit the target behavior to engage the toddler with Austim Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in communication and social interactions. This learning module describes a process for engaging toddlers with ASD in social and communication interactions.

Overview of Naturalistic Intervention

![]()

After reviewing this overview section, you should be able to answer the following questions about this practice:

What is Naturalistic Intervention?

Why use Naturalistic Intervention?

Where Can You Use Naturalistic Intervention?

What is the Evidence-base for Naturalistic Intervention?

What is Naturalistic Intervention?

![]()

Naturalistic Intervention is a collection of practices including environmental arrangement, interaction techniques, and strategies based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) principles, such as modeling and time delay. These practices are designed to help toddlers develop skills in the areas of communication (both prelinguistic and linguistic) and social development by responding to the toddler in ways that are naturally reinforcing, appropriate to the interaction, and build up to more elaborate behaviors. By definition, naturalistic intervention is used across settings and within routines and activities that occur throughout the day by anyone trained in the intervention processes.

Interventionists may be:

- teachers

- educational assistants

- therapists

- child care providers

- parents

- other family (e.g., grandparents, older siblings)

- community members (e.g., librarians)

Embedding the intervention into a toddler’s natural environment and daily activities encourages generalization of skills and allows the adult to use their insights about a toddler’s interests and expand upon them to reach target behaviors. Naturalistic intervention has demonstrated effectiveness with toddlers with ASD and is appropriate for toddlers of any cognitive level.

A naturalistic intervention is guided by assessment information as well as the daily routines and activities in which the toddler participates. The assessment may include toddler activities that occur at home (e.g., dressing, eating, bathing and bedtime), at a family child care provider’s home (e.g., play time, snack, nap), or at a child care center (e.g., art project, movement time). These activities provide baseline data on the toddler’s behaviors and skills. This module will provide examples of assessment tools and strategies for identifying family routines and activities, including toddlers’ interests. Conversations and structured interviews with families and other team members will help the intervention team identify appropriate activities and routines into which naturalistic intervention can be embedded. Naturalistic interventions also rely upon understanding and building upon a toddler’s interests, which will need to be assessed.

Next, assessment information is used to set target behaviors and identify the environments and interactional contexts in which the target behavior may be elicited. The first approach is to set up the environment with high interest activities to naturally engage the child in social and communication interactions. Data analysis may indicate that ABA strategies are needed to add more structure to the naturalistic context of daily routines and activities. In this instance, the intervention team modifies their naturalistic intervention to include one of these ABA strategies: modeling, mand-model, time delay and incidental teaching.

Data are collected and used on an ongoing basis to determine the success of the naturalistic intervention and/or to modify the intervention. This may include increasing the complexity of the target behavior when it has been successfully met or more intentionally using ABA strategies to strengthen the naturalistic intervention.

Why Use Naturalistic Intervention?

![]()

Motivating a toddler with ASD to initiate communication and engage in social interactions can be very challenging. Identifying and building upon a toddler’s interests and working within daily routines and activities offer opportunities to increase meaningful engagement. Naturalistic intervention provides a way for just about anyone in a toddler’s life to learn strategies for interacting with the toddler in any setting where the child spends time. The intervention starts with the toddler’s interests, is planned around baseline data, and provides strategies to meet targeted behaviors.

Naturalistic interventions also provide guidance in structuring environments to elicit targeted behaviors.

Where Can a Naturalistic Intervention System be Used and By Whom?

![]()

Naturalistic intervention can be implemented in any setting where a toddler spends time, by parents and a variety of other appropriately trained adults, to support the acquisition of target behaviors in the areas of communication (prelinguisitic and linguistic) and social development. Parents, other family members (such as siblings, grandparents), early interventionists (such as teachers and therapists), child care providers, and community members (e.g. clergy, librarians) who have received training in the toddler’s naturalistic intervention may all be appropriate team members.

It is important to have a designated lead that will include all of the identified adults in planning and provide training in the specifics of a toddler’s naturalistic intervention. All participants will require some training in how to elicit the target behavior and collect data; some may need frequent training and ongoing coaching. At times, it may be appropriate to include siblings or other children in a naturalistic intervention. When that is the case, clear adult guidance and support is needed.

How are some ways naturalistic intervention can enhance communication and social skills that occur within everyday toddler activities and routines?

How are some ways naturalistic intervention can enhance communication and social skills that occur within everyday toddler activities and routines?

-

Initiating communication with a sibling during play time at home.

-

Engaging in two way communication during play time in a center-based program.

-

Using words to request “more” during snack or meal times.

-

Making a choice for a preferred bedtime story.

By using naturalistic interventions for target behaviors within specific routines such as those described above, responses can be strategically elicited and expanded upon to generalize skills to other routines and activities.

EXAMPLE

If a child is successful in learning to use the word, “more” to request more snack, the toddler is encouraged with similar strategies to use “more” to request more food in a restaurant or to request “more” of a preferred activity.

What is the Evidence-Base for Naturalistic Intervention?

![]()

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC) reviewed and updated the literature on evidence-based, focused intervention practices previously conducted by NPDC.

- A total of 27 EBPs are identified in the current review.

- A total of 10 of these practices meet the criteria and have been shown effective with infants and toddlers with ASD.

The practices were identified as evidence-based when at least two high quality group design studies, five single case design, or a combination of one group design and three single case designed studies showed that the practice was effective. The full report is available on the NPDC on ASD website.

Naturalistic intervention meets the evidence-based practice criteria in the birth to elementary age groups with 10 single case design studies. For the infant and toddler age group, one single-subject design study included toddlers with autism and demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting the development of communication (Ingersoll, et al., 2005). Naturalistic intervention has been used effectively to address social, communication, behavior, joint attention, play, and academic skills. A complete list of the research evidence-base literature for children aged birth to five is included in the Module Resources section.

Refer to the Naturalistic Intervention Fact Sheet from the updated EBP report for further information on the literature for naturalistic interventions.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What are some key advantages of using naturalistic intervention?

Question:

What are some example of target behaviors that may be appropriately addressed through a naturalistic intervention?

Implementation Steps

After reviewing this section, you should be able to recognize the basic steps for using this practice.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

Step 1 for implementation of Naturalistic Intervention involves planning the intervention. In this step, you will review steps for identifying a target behavior, collecting baseline data, identifying contexts for the intervention, providing training to the early intervention team, and preparing the environment for the intervention.

Step 1.1 Identify a Target Behavior

First, it is important to identify specific, measurable skills for the target behaviors of a naturalistic intervention. These skills need to be more specific than a general goal or outcome and include behaviors that can be observed.

a) Select a specific target behavior to be the focus of the intervention in these areas:

- pre-linguistic or linguistic communication and/or

- social skills

The target behavior should represent team consensus and come from outcomes on the toddler’s Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) or other individualized plan.

General Outcome or Goal |

Target Behavior |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Home-based Example: Tony will play with his parents. |

Tony will share attention around a preferred toy with his parents for 3 minutes during five routines within his day, five days a week. |

||

|

Center-based Example: Kate will initiate communicaiton with peers. |

Katie will ask one question of a peer during a 15 minute play period, six times throughout her day. | ||

b) Confirm that target behaviors are derived from outcomes in the toddler’s IFSP or other individualized plan

The target behaviors identified for naturalistic intervention are generated from the IFSP developed by the toddler’s IFSP team. The IFSP team, which includes early interventionists and parents, meets to determine appropriate outcomes and target behaviors for the toddler.

Early interventionists (EI) may include the following:

Early interventionists (EI) may include the following:

- service coordinators

- special education teachers

- general education teachers

- speech-language pathologists

- occupational therapists

- physical therapists

- psychologists

- child care providers

When focusing on toddlers with ASD, it is important to recognize and understand the value of prelinguistic communication in setting target behaviors. For example, a target behavior may be pointing to an object to establish shared attention, engaging in shared attention, or vocal turn-taking. Although none of these target behaviors demonstrates actual language use, these skills provide the foundation for language development.

For video clips demonstrating shared attention and other pre-linguistic behaviors, see the ASD Video Glossary found on the Autism Speaks website.

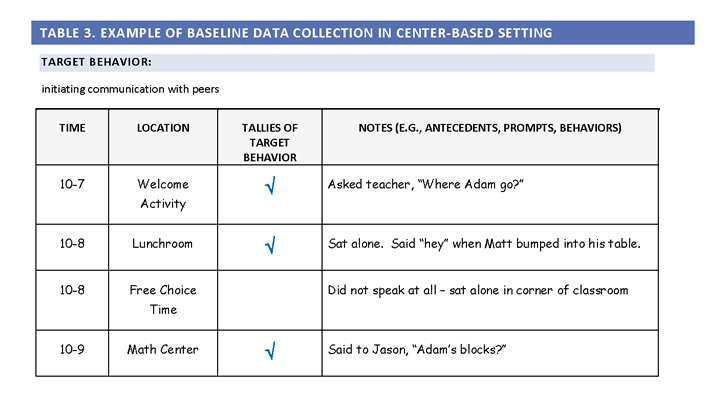

Step 1.2 Collect baseline data

It is important to have a clear understanding of the toddler's baseline skills before beginning a naturalistic intervention.

Take data on the target skill or behavior a minimum of three times in more than one environment on more than one day.

A frequency log of how often these behaviors occur in a variety of settings may be useful when collecting data. These baseline data will be critical for assessing whether or not the intervention is effective.

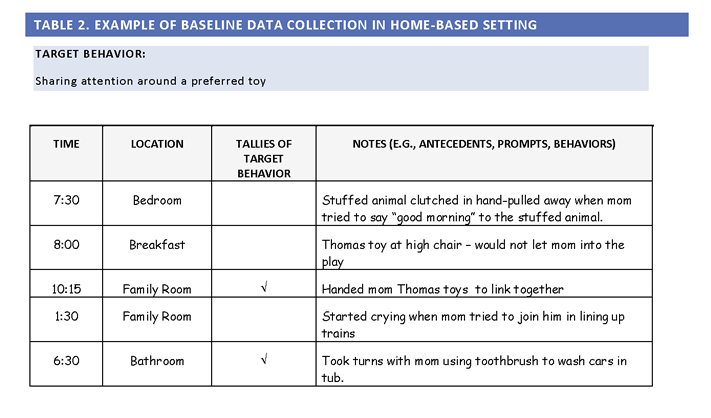

Example of Baseline Data Collection in a Home-based Setting

Example of Baseline Data Collection in a Center-based Setting

With information from a log like these, you can identify how frequently toddlers currently use the target behavior. In the notes column, you might indicate prompts that were used, environmental cues, or other antecedents to the demonstration of the target behavior.

Language sampling can provide useful information about toddlers who are using words or phrases regularly. A language sample will provide information on the current length and content of utterances as well as antecedents to their production. A speech/language pathologist (SLP) on the toddler’s team should be able to take and analyze a language sample.

Step 1.3 Identify the contexts for intervention

Naturalistic intervention takes place throughout the day in the context of daily routines and activities. Being intentional about implementing interventions within the context of a toddler’s regular routines and activities is critical for successfully implementing naturalistic intervention.

a) Determine the toddler’s schedule of typical routines and activities

This includes activities in home, center, and other community settings. The schedule is often done on a weekly basis. Consider that all families have activities, but they may or may not occur in the same order or sequence each day or week. Therefore, it is important to use the schedule to guide planning for a naturalistic intervention, and to recognize that schedules may change as child and family circumstances change.

b) Identify activities that are of interest and highly reinforcing for the toddler

An important part of discovering the context for a toddler is to learn about a toddler’s interests and the activities that are highly reinforcing. There are several useful tools and strategies for obtaining this information.

The Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklists includes the Early Preschool Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist for infants and toddlers functioning below 15-18 months of age and the Middle Preschool Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklists for use with children functioning between 15 - 36 months of age. Both checklists help identify a toddler’s interests and potential learning opportunities within everyday routines and activities. (Swanson, Raab, Roper & Dunst, 2006)

Another tool is Getting to Know Your Child, from the Family-Guided Routines-Based Intervention Model (Woods, 2013). This tool provides open-ended space for writing in a toddler’s favorite and least favorite activities in a number of categories to help identify interests and opportunities for working on a target behavior. These resources are applicable to both home and center-based settings.

c) EI team members and the family identify contexts in which to embed naturalistic

intervention

Toddler-directed Activities

In these activities, toddlers select what they want to do within a specific environment. These preferred activities are then used to elicit the target behavior. Knowing these activities ahead of time by completing one of the strategies or tools described in Step 1.2 contributes to a toddler-directed intervention.

Home-based Example: Tom’s family wants him to engage in more interactions with Tom. They developed a target behavior related to turn taking. Tom’s mom, Norah is finishing up lunch dishes. Tom opens the cabinet and pulls out pots and pans. He starts to bang on one with a wooden spoon. Tom’s mom crouches down with him and extends a hand, nonverbally asking for a turn with the spoon. They trade the spoon back and forth.

Center-based Example: Betsy has a target behavior of labeling animals. Different animal toys are offered during free-choice time, and Betsy decides that she wants to work on an animal puzzle after math center time. To support Betsy’s use of the target behavior, the team member may encourage Betsy to request each piece that represents a different animal.

Routines and Activities

Routines and activities that take place on a regular basis (e.g., bath time, getting into the car seat, breakfast, snack and playtime, going to the grocery store) offer natural opportunities for learning and practicing target behaviors. Choice making should be built into these routines and activities, thus allowing toddlers to direct the interactions.

Home-based Example: Deone has a target behavior of pointing to request. During bathtime, his mother periodically holds up two different bath toys so that Deone can point to the toy he wants to play with.

Center-based Example: Devin has a target behavior of using words to request, “more.” Each day during snack, his teacher presents several tasty options (pretzels, apple slices, cheese cubes, and pudding). She keeps these out of reach and gives very small portions to the students upon their request. These small portions provide the children, including Devin, with numerous opportunities to request, “more.” Having multiple snack options allows Devin to make choices and direct the interaction.

Strategies for conducting routines-based assessments with families are available from the following national resources. These sites include resources and strategies for identifying home and center-based routines and activities as well as a guidance for mapping community resources to inform opportunities for addressing target behaviors.

-

Project TaCTICS, Florida State University (Juliann Woods)

-

Early Intervention in Natural Environments, Siskin Institute, Chattanooga, TN (Robin McWilliam)

Many of the Siskin Institute resources are published in this book: McWilliam, R.A (2010). Routines-based Early Intervention: Supporting Young Children and Their Families. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company

-

The Donovan Family Case Study: Guidance and Coaching on Evidence-based Practices for Infants and Toddlers with ASD (National Professionals Development Center on ASD, 2013) includes additional resources for identifying the contexts for developing a naturalistic intervention.

Planned Activities

Planned activities are set-up in advance to provide opportunities for individual toddlers to practice target behaviors such as choice-making, labeling objects, or initiating a verbal communication.

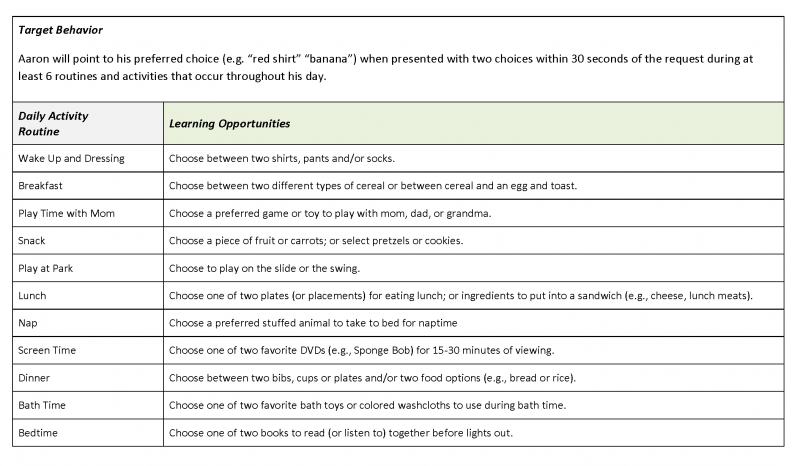

View Examples of Learning Opportunities Within Daily Routines and Activities to Practice Targeted Behaviors

Naturalistic interventions can be embedded within learning opportunities that may occur throughout a toddler’s day at home. The examples illustrate the range and diversity of naturally occurring learning opportunities that occur within daily routines and activities for increasing achievement of target behaviors.

The learning opportunities create the learning context for arranging the environment to elicit the target behavior(s) and establishing how the adult responds to reinforce the toddler’s response or uses intentional evidence-base strategies to expand upon the toddler’s responses. See Step 2 for a description of these processes.

Visit the Autism Internet Modules (AIM) website on the Naturalistic Intervention module for a similar example for a toddler who spends the majority of his time in an early childhood classroom.

Step 1.4 Identify and provide training to the early intervention team

Since naturalistic interventions occur throughout the day, several adults may need to be taught how to elicit the target behavior.

a) Decide who will teach the skill

Identify the early interventionist(s), family members, and other adults who will facilitate the interactions to elicit target behaviors. These adults may include parents and other family members, teachers, caregivers, therapists, paraprofessionals, other community members and volunteers. Having multiple adults interact with the toddler encourages generalization. Adults who naturally interact with toddlers should be prepared to use naturalistic intervention strategies.

b) Provide adequate training to adult team members involved in the intervention before initiating naturalistic intervention

Adults who will be interacting with learners must understand:

- the target behavior including how it will be observed and measured,

- strategies used to elicit and reinforce that skill, and

- data collection strategies used to assess baseline and monitor progress toward achieving target behaviors.

Depending on the situation, different levels of training may be necessary. For example, in a center-based setting, the teacher may need to arrange the environment and model the strategies used to elicit the skill for assistants and volunteers. An early intervention home visitor might teach strategies to parents and older siblings.

All learning facilitators must understand the entire process to successfully use naturalistic strategies at appropriate times throughout the day. Coaching and ongoing support with a team lead and/or professional development consultant may be required to achieve consistency and success in implementing naturalistic intervention throughout the day when multiple adults and settings are involved.

c) Develop a training plan

It is useful to develop a plan that identifies the full team of people who are involved in a naturalistic intervention and what type of training, support, and ongoing coaching each member will receive based on their needs and roles. The plan should also include the team leader and how the training will be carried out.

Although some naturalistic practices, such as milieu teaching, have traditionally been implemented by teachers and therapists, research also has demonstrated the effectiveness of training parents, caregivers, and/or other professionals to implement the teaching. Parents are often taught specific parts of the practice, such as reciprocal interaction techniques, while the toddler also participates in sessions that involve behavioral techniques such as modeling to elicit responses (within an environment adapted for the toddler’s own interests). Parents also can be taught to implement all aspects of the intervention in home and community settings. Parent involvement may be especially important for infants and toddlers, for whom multiple therapy sessions per week in a clinic or other out-of-home settings may not be appropriate. In these situations, parents are often the most appropriate and most effective intervention partners.

Refer to the AIM module on Parent Implemented Interventions for more information on this topic.

The training of team members is essential to ensure all identified interventionists understand the step-by-step directions for eliciting the target behavior.

Scripts provide a way to ensure that step-by step directions are available to all team members.

Sample scripts can be found in Step 2.2a.

Video Segment: Naturalistic Intervention Requesting Snack

Video Segment: Naturalistic Intervention Requesting Snack

This video demonstrates training strategies that may be effective in preparing parents and other early intervention team members to implement a naturalistic intervention. Parents are shown in a session with their toddlers while an interventionist demonstrates and describes various aspects of using naturalistic interventions focused on target behaviors related to, "making requests for a snack."

Step 1.5 Arrange the environment to elicit the target behavior

Use information from Step 1.3 Identify the contexts for intervention and materials or resources within the home, center, and other community environments to capture a toddler’s attention and motivate him/her to produce target behaviors.

a) Choose motivating materials and activities to engage the toddler and

promote the use of targeted skills.

A key feature of naturalistic intervention is using materials and toys that will motivate the child to engage in the target behavior and that will promote generalization of skills. This is the place in the process to refer back to the information gathered about the toddler’s interests to help select highly motivating toys and activities. For a toddler’s safety, choose age appropriate toys that are designed to be mouthed, have smooth surfaces, can be easily grasped, and are washable.

Toys and activities that can be particularly useful in facilitating communication and social play include those that require fine motor and eye-hand coordination, adult assistance, and turn-taking.toys that have multiple parts requiring fine motor skills and eye hand coordination.

EXAMPLES OF TOYS AND ACTIVITIES THAT CAN BE USED WITH NATURALISTIC INTERVENTION

Toys:

- DuplosTM blocks

- a shape sorter

- Mr. Potato HeadTM

Items that can be added onto another activity:

- adding Little PeopleTM into play with blocks

- using puppets to act out a story

- hiding items under nesting cups

Activities that require adult assistance:

- opening a kitchen cabinet to obtain a snack

- having lid on bottle of bubbles so tight that learner must request help

- holding puzzle pieces until the child requests them

Activities that ecourage turn-taking:

- throwing a ball

-

placing puzzle pieces

- sending toy cars down a ramp

- blowing bubbles

Social routines:

- finger plays or songs

- peek-a-boo game

- tickling games between a parent and child

For additional ideas on choosing toys for toddlers, visit the Zero to Three website: Tips for Choosing Toys for Toddlers.

b) Manage and distribute materials in a way that encourages a toddler to

communicate

Within interactions and contexts for intervention, materials are managed by the lead interventionist (e.g., parent, educator).This means that the interventionist and/or parent is “the keeper of the goods” and distributes the materials in a manner that encourages communication. For example, communication can often be elicited by giving toddlers only a few of the DuplosTM at once, forgetting to open a food package for snack, or putting a doll’s hat on her feet as if by accident. Such “mistakes” are likely to elicit a request or comment from the toddler.

c) Arrange the intervention context and prepare the environment

Arrange the environment to encourage the use of the target behavior or skill and maintain the toddler's interests.

Home-based Example: Mica’s team has identified his target behavior to be pointing to request (a pre-linguistic communication skill). Her mother knows that he loves to put shapes in her shape sorter.

She takes Mica’s shape sorter out of the toy box and puts it on the couch out of Mica’s reach, but within her view. The intention is for Mica to point to the shape sorter to request it.

Center-based Example: Gus’s team has identified his target behavior to be requesting a snack from his peers. His favorite foods are placed in bowls out of his reach and near his peers. The interventionist announces that Gus’s favorite snack is in the bowl. The intention is for Gus to request the snack from his peers and to stay with the session long enough to also respond to his peer’s request for Gus to pass the snack to them.

Practice Scenarios: Planning Naturalistic Intervention

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) that follow a toddler case through each of the implementation steps, following the Knowledge Check. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips.

Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist completed for Noah

Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist completed for Noah

Baseline Data Chart: Record baseline data for Noah on the priority target behavior

Baseline Data Chart: Record baseline data for Noah on the priority target behavior

Knowledge Check

Question:

Why is it important to provide training to all of the people who will be implementing a naturalistic intervention?

Question:

Identify and describe at least three types of assessments that will identify the contexts for a naturalistic intervention with Anna.

Step 2 Implementing Naturalistic Intervention

![]()

This section describes how to implement naturalistic intervention. To begin using naturalistic intervention, elicit the target behavior using interaction techniques and, if necessary, behavioral strategies like prompting and modeling. It is most common for interaction and behavioral techniques to be used in combination with one another, thereby providing both the foundation of the interaction and the specifics on how the adult interacts with the toddler. In some cases, interaction techniques will be sufficient to elicit the target behavior, and further prompting will not be necessary.

Step 2.1 Engage the toddler in an interaction

Engage the toddler in language-rich and child-directed interactions, making sure you are highly attuned and responsive to the communicative attempts of the toddler. You should also aim to use a toddler’s interests and provide language models that are at a slightly higher level than the toddler’s own language to elicit a target behavior.

Following are some strategies that can be used to maintain a toddler’s interests and provide language models that are at a slightly higher level than the toddler’s own language use. For some toddlers, these techniques will facilitate their use of the target behavior.

Techniques Used to Engage Toddlers

Team members engage the toddler in a language-rich, child-directed, and reciprocal interaction that involves a variety of techniques. The following examples are described in more detail.

a. Following the toddler's lead

b. Being at the toddler's level

c. Responding to the toddler's verbal and nonverbal initiations

d. Providing the toddler with meaningful verbal feedback

e. Expanding the toddler’s utterances

Continue to review details of each technique.

Step 2a. Following the toddler’s lead

Following the toddler’s lead involves allowing the child to direct the interaction and the activity. Rather than the interventionist having a set plan (e.g., to play in the toy house), she waits and sees what the toddler wants to do. If the toddler goes to the toy house, she engages him there; and, if the child goes to the block area, she engages him with the blocks. Remember that the environment has already been arranged to elicit specific targets, so either activity should lead to the desired target.

For some toddlers, the interventionists must be especially observant and patient in order to follow the toddler’s lead. If a toddler has a more passive temperament, it may be difficult to entice the toddler to seek out his or her interests. When this occurs, the interventionist may be tempted to become more directive. For example, an interventionis might say to a toddler, “Here’s a puzzle! Let’s do it!”

However, the interventionist is encouraged to be patient, watch for nonverbal indications of interest (such as the toddler reaching for the puzzle), and match the toddler’s activity level. An example of this might be if the toddler is pouring sand over and over, the interventionist might join the toddler in this activity rather than encouraging her to make a sandcastle.

Step 2b. Being at the toddler’s level

With toddlers, being at their level often means that the interventions may have to lie or sit on the floor while the child is on the floor or couch to share face-to-face interactions. This kind of positioning facilitates shared attention, which is crucial to the interactions.

For toddlers who avoid eye contact, it may be necessary for the interventionist to maneuver her own body to interrupt the toddler’s eye gaze. That is, if the child is looking toward the clock while playing with a koosh ball, the interventionist may need to put her own face in the line of the clock to encourage eye contact and establish shared attention. However, if a toddler finds eye contact unpleasant and is actively avoiding eye contact, it may be best to engage the toddler in an interaction without insisting upon eye contact.

Step 2c. Responding to the toddler’s verbal and nonverbal initiations

When joining toddlers in play, interventionists must be vigilant in watching for toddlers’ communicative cues. A child who wants a snack that is out of reach may glance toward it and vocalize. An attuned interventionist recognizes this as a communicative attempt and responds. Being aware of even the most subtle communicative attempts and responding to these attempts teaches the toddler that communication is powerful. Catching these subtle attempts reduces missed opportunities for engagement, a common error in learning to respond to a toddler’s initiations, especially for toddlers with less apparent or infrequent communication and social behaviors.

Step 2d. Engaging toddler with verbal and motor imitation

This imitation can encourage turn-taking and facilitate the back-and-forth dance of social communication.

EXAMPLE

If a child holds a puzzle piece up to her face and says, “ga,” the interventionist can hold a puzzle piece up to his own mouth and say, “ga.”

Interrupting a routine with a pause or doing something novel that the toddler finds funny or interesting can keep a toddler engaged in an interaction.

EXAMPLE

Make a funny face as you reveal yourself after a few rounds of peek-a-boo or pause at the end of a line of a song, “The itsy bitsy spider went up the water...”

Step 2e. Providing the toddler with meaningful verbal feedback

Responding to a toddler’s communicative attempts with words, or meaningful verbal feedback, gives the child a model while they are sharing attention with the interventionist.

EXAMPLE

A minimally verbal toddler may be trying to place a puzzle piece and say,

“Ta!”

The interventionist, available and engaged, can respond,

“Stuck! That piece is stuck! Let’s turn it.”

Step 2f. Expanding the toddler’s utterances

When a toddler is verbal, especially at the one- to three-word phrase level, the interventionist can build on what the toddler says, thereby demonstrating more linguistically sophisticated options, as in this script:

Toddler (with toy cars): “Car.”

Interventionist (pushes car): “Car. Go, car!”

Toddler: “Go, car!”

Interventionist: “Go, car! Fast!”

Step 2 Video example of naturalistic strategies used in a play session

For most children with ASD, it will be necessary to provide additional supports and strategies for learners to demonstrate the target behaviors.

Video: Naturalistic Intervention Strategies as Additional Supports

This video segment gives a brief snapshot of how a play session on the floor may be conducive to eliciting target behaviors by using the strategies described.

Step 2.2 Use strategies based on applied behavior analysis to elicit target behaviors

Use modeling, mand-models, time delay, and/or incidental teaching techniques to elicit the target behavior within intervention contexts and arranged environments that were identified in Step 1.3.

Sometimes, engaging the toddler in a language-rich and responsive interaction within an arranged environment will result in the learner demonstrating the target behavior. However, if the toddler does not demonstrate the target behavior, applied behavior analysis (ABA) techniques can be used to elicit the target behaviors. This should still be within the context of an arranged environment and with an interventionist who is using responsive interaction techniques.

These strategies can be used with pre-linguistic toddlers, with some modifications. Instead of expanding on a verbal response, the communication partner would map language onto the target behavior, such as pointing.

Applied Behavior Analysis Interventions

- Modeling,

- Mand-modeling,

- Modified time delay

- Incidental teaching

Review more about each ABA intervention.

Modeling

Modeling is a verbal or visual demonstration of the correct response requested of a toddler.

Team members implement modeling by:

- establishing shared attention,

- presenting a verbal or physical model,

- expanding the response and providing the requested material (if the toddler responds to the model correctly),

- providing another model (if the toddler does not respond or is inaccurate),

- expanding the response and providing the requested material (if the toddler responds to the model correctly), and

- stating the correct response and providing the material (if the toddler does not respond or does not repeat the model correctly).

Mand-Modeling

Mand-model procedures incorporate a question, choice, or direction (mand) into the activity prior to initiating a modeling procedure.

Team members implement mand-modeling by:

- establishing shared attention;

- presenting a verbal direction (mand) or question;

- expanding the response and providing the requested material (if the toddler responds correctly);

- giving another direction or model (depending on the toddler’s needs for support), if the toddler does not respond or does not respond with a target;

- expanding on the response and providing the requested material (if the toddler gives the target response); and

- saying the target response and providing the material (if toddler still does not give the target response or repeat the model exactly).

Modified Time Delay

Time delay is a practice that focuses on fading the use of prompts during activities. With this procedure, a brief delay is provided between the initial requests/questions and any additional instructions or prompts. The use of modified time delay, or waiting, before providing a verbal prompt allows toddlers to initiate the verbalization and encourages them to become aware of nonverbal cues.

Interventionists implement modified time delay by:

- establishing shared attention;

- waiting 3-5 seconds for the toddler to make a request/comment;

- expanding on the request/comment and providing the requested material/activity (if the toddler initiates at the target level);

- providing a mand or model, depending on the toddler’s need for support (if the toddler does not initiate at the target level;

- expanding on the response and providing the material (if the toddler responds correctly);

- saying the target response and providing the material (if the toddler still does not give the target response or repeat the model exactly).

Incidental Teaching

Incidental teaching can be used to help toddlers elaborate on requests they have made. The interventionist encourages the learner to initiate interactions and manipulates the environment to elicit a request, and then uses a question to encourage an elaboration from the toddler.

Team members implement incidental teaching by:

- setting up the environment to encourage learners to request assistance or materials,

- waiting for learners to initiate the request,

- responding with a request for elaboration (if the learner does not initiate with the target response),

- continuing to prompt for elaboration until the learner responds appropriately, and

- using model, mand-model, or modified time delay procedures, depending on the needs of the learner (if the learner does not initiate a request).

(Adapted from Hancock & Kaiser, 2006)

Practice Scenario: Implementing Naturalistic Intervention

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Knowledge Check

Question:

When may it be necessary to use applied behavior analysis (ABA) strategies in a naturalistic intervention?

Question:

Name the four applied behavior analysis interventions that are used to elicit target behaviors within naturalistic contexts.

Step 3 Monitoring Progress

![]()

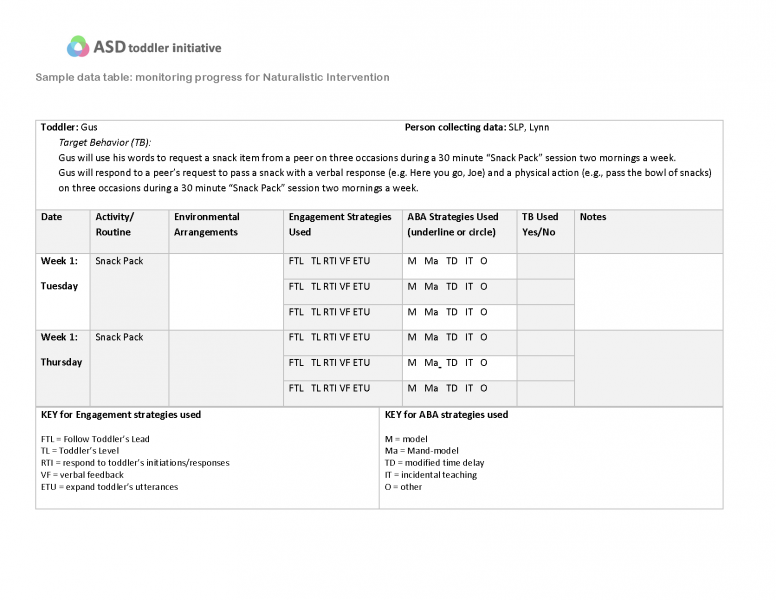

During the monitoring step, you will gather data throughout naturalistic interventions to determine the success of the intervention and guide future decision-making.

Step 3.1 Gather and record data

Develop a system to monitor the effectiveness of the intervention that outlines where, when, by whom, and how data are collected.

Monitor the frequency and duration of the interfering behavior and the

replacement behavior

Collect data to monitor the toddler's progress. Data will be collected at planned time periods by taking language samples and/or other data (for example, frequency counts) on strategies that were used to elicit the targeDt behavior. Because naturalistic intervention involves having the conversational partner engaged with the toddler, it can be helpful to either:

- video record the session and collect data off the video at a later point in time or

- have an observer take the data.

However, this may not always be possible, especially in home-based settings where real-time data collection is the most feasible. Then, the interventionist or parent would want to use data collection measures and procedures that are easily accessible during intervention and efficient. This may involve making marks on a piece of masking tape applied to a hand or selecting off tallies on a tablet or smart phone.

Gus will use his words to request a snack item from a peer on three occasions during a 30 minute “Snack Pack” session two mornings a week.

Gus will respond to a peer’s request to pass a snack with a verbal response (e.g. Here you go, Joe) and a physical action (e.g., pass the bowl of snacks) on three occasions during a 30 minute “Snack Pack” session two mornings a week.

Example of data collection procedures that may be used real time in home and center-based settings:

-

Wrapping paper or masking tape around one’s wrist on which data can be tallied.

-

Placing data collection sheets near the location of the activity.

-

Gathering data from multiple toddlers in a center-based group on address labels that can later be peeled off and put on individual toddlers’ data sheets.

-

Using technology such as tablet or smart phone to click off data.

Step 3.2 Analyze data to determine next steps

Compare intervention data and baseline data to determine the effectiveness of the

intervention

Review and analyze the data on a periodic and agreed upon basis. This helps to determine what the data indicates about progress toward meeting a toddler’s target behavior. Use the data to assess whether the naturalistic intervention is achieving the desired results or if it may need to be modified. Through data analysis, you may discover that the target behavior has been met and that the goal needs to be ramped up to a more complex response.

Summarize the data to make decistions about future planning

For a naturalistic intervention, there are important decision-making points between engagement and use of ABA strategies when the early intervention team has to decide if the engagement strategies are sufficient for eliciting and reinforcing the target behavior. Careful consideration of the data helps the intervention team identify which ABA strategy may work the best to elicit a target behavior. Also, data will be useful in determining if other environmental arrangements are needed or if additional training may be required by members of the intervention team.

Together with the team, you may decide that additional data is needed to gain a better understanding of how to modify a naturalistic intervention.

Practice Scenario: Monitoring Naturalistic Intervention

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Knowledge Check

Question:

Which of these elements provide useful data for analyzing the effectiveness of a naturalistic intervention?

A. quantitative data (frequency and duration)

B. observational notes

C. environmental arrangements

D. specific routine or activity

Question:

What are some reasons why is it important to identify the activity or routine and the environmental arrangement when collecting data on a naturalistic intervention?

Module Resources

View a description for each of the module resources

![]() Implementation Checklist for Naturalistic Intervention

Implementation Checklist for Naturalistic Intervention

Parent & Practioner Practice Guide for for Naturalistic Intervention

Parent & Practioner Practice Guide for for Naturalistic Intervention

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

Sample Data Sheets

Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist completed for Noah

Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist completed for Noah

Baseline Data Chart: Record baseline data for Noah on the priority target behavior

Baseline Data Chart: Record baseline data for Noah on the priority target behavior

Sample Section of Naturalistic Intervention Training Plan for Noah

Sample Section of Naturalistic Intervention Training Plan for Noah

Supplemental Resources for Naturalistic Intervention

Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklists (Swanson, Raab, Roper & Dunst, 2006). From the Family, Infant, and Preschool Program (FIPP). This includes the Early Preschool Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist) for infants and toddlers functioning below 15-18 months of age, and the Middle Preschool Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklists for use with children functioning between 15 and 36 months of age. Both checklists help identify a toddler’s interests and potential learning opportunities within everyday routines and activities.

Getting to Know Your Child, from the Family-Guided Routines-Based Intervention Model (Woods, 2013).

Coaching: The Donovan Family Case Study: Guidance and Coaching on Evidence-based Practices for Infants and Toddlers with ASD ( National Professionals Development Center on ASD, 2013) includes additional resources for identifying the contexts for developing a naturalistic intervention.

Early Start Denver Model: Rogers, S.J., Dawson, G. (2010). Early Start Denver Model for Young Children with Autism: Promoting Language, Learning, and Engagement. New York: Guilford Press.

Language Sample Analysis: Heilmann, J.J. (2010 ). Myths and realities of language sample analysis. ASHA Journal: Perspectives.

Bowen, C. (2013). Structural Analysis of Language Sample.

Routines Based Assessments: Strategies for conducting routines-based assessments with families are available from the following national resources. These sites include resources and strategies for identifying home and center-based routines and activities as well as a guidance for mapping community resources to inform opportunities for addressing target behaviors. Project TaCTICS, Florida State University (Juliann Woods).

Early Intervention in Natural Environments, Siskin Institute, Chattanooga, TN (Robin McWilliam)

References

Research Articles for the Birth to 3 Year Age Group

Ingersoll, B., Dvortcsak, A., Whalen, C., & Sikora, D. (2005). The effects of a developmental, social—Pragmatic language intervention on rate of expressive language production in young children with autistic spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(4), 213-222. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200040301.

Research Articles for the 3 to 5 Year Age Group

|

Hancock, T. B., & Kaiser, A. P. (2002). The effects of trainer-implemented enhanced milieu teaching on the social communication of children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(1), 39-54. doi: 10.1177/027112140202200104 |

|

Ingersoll, B., Dvortcsak, A., Whalen, C., & Sikora, D. (2005). The effects of a developmental, social—Pragmatic language intervention on rate of expressive language production in young children with autistic spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(4), 213-222. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200040301 |

|

Koegel, R. L., Koegel, L. K., & Surratt, A. (1992). Language intervention and disruptive behavior in preschool children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 22(2), 141-153. doi: 10.1007/BF01058147 |

|

Koegel, R. L., Camarata, S., Koegel, L. K., Ben-Tall, A., & Smith, A. E. (1998). Increasing speech intelligibility in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(3), 241-251. doi: 10.1023/A:1026073522897 |

|

Koegel, L. K., Carter, C. M., & Koegel, R. L. (2003). Teaching children with autism self-initiations as a pivotal response. Topics in Language Disorders, 23(2), 134-145. doi: 10.1097/00011363-200304000-00006 |

|

Kohler, F. W., Anthony, L. J., Steighner, S. A., & Hoyson, M. (2001). Teaching social interaction skills in the integrated preschool an examination of naturalistic tactics. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 21(2), 93-103. doi: 10.1177/027112140102100203 |

|

McGee, G. G., & Daly, T. (2007). Incidental teaching of age-appropriate social phrases to children with autism. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32(2), 112-123. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.2.112 |

|

Olive, M. L., De la Cruz, B., Davis, T.N., Chan, J.M., Lang, R.B., O'Reilly, M.F., & Dickson, S.M. (2007). The effects of enhanced milieu teaching and a voice output communication aid on the requesting of three children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1505-1513. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0243-6 Seiverling, L., Pantelides, M., Ruiz, H. H., & Sturmey, P. (2010). The effect of behavioral skills training with general‐case training on staff chaining of child vocalizations within natural language paradigm. Behavioral Interventions, 25(1), 53-75. doi: 10.1002/bin.293 |

|

Whalen, C., & Schreibman, L. (2003). Joint attention training for children with autism using behavior modification procedures. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(3), 456-468. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00135 |

All Other Ages Research

Naturalistic Intervention Fact Sheet

Other Resources

Autism Internet Modules. http://www.autisminternetmodules.org

Hancock, T. B. & Kaiser, A. P. (2006). Enhanced milieu teaching. In R.J. McCauley, & M.E. Fey, (Eds.), Treatment of language disorders in children (pp. 203-229). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Hwang, B., & Hughes, C. (2000). The effects of social interactive training on early social communicative skills of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(4), 331-343.

Ingenmey, R., & Van Houten, R. (1991). Using time delay to promote spontaneous speech in an autistic child. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(3), 591-596.

Kaiser, A., Hancock, T., & Nietfeld, J. (2000). The effects of parent-implemented enhanced milieu intervention on the social communication of children who have autism. Early Education and Development, 11(4), 423-446.

Koegel, R., O’Dell, M., & Koegel, L. (1987). A natural language intervention paradigm for nonverbal autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 17(2), 187-200.

Matson, J., Sevin, J., Box, M., & Francis, K. (1993). An evaluation of two methods for increasing self-initiated verbalizations in autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(3), 389-398.

Miller, J. F., Long, S., McKinley, N., Thormann, S., Jones, M., & Nockerts,A. (2005). Language sample analysis II: The Wisconsin guide. Madison,WI: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Neef, N., Walters, J., & Egel, A. (1984). Establishing generative yes/no response in developmentally disabled children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 17(4), 453-460.

Pretti-Frontczak, K., & Bricker, D. (2007). An activity-based approach to early intervention. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Sussman, F. (1999). More than words: Helping parents promote communication and social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Toronto, ON: The Hanen Centre.

Wong, C., Kasari, C., Freeman, S., & Paparella, T. (2007).The acquisition and generalization of joint attention and symbolic play skills in young children with autism. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32(2), 101-109.

Glossary

Module Evaluation Survey

Please take a moment to provide valuable feedback for this learning module. Use the "Take the Module Evaluation Survey" link below to begin the evaulation.