Pivotal Response Treatment

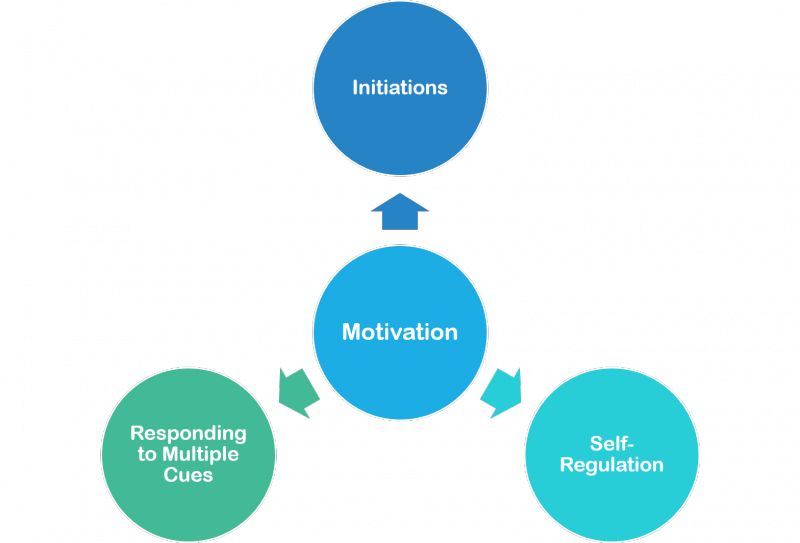

This module describes a naturalistic behavior intervention model called pivotal response treatment (PRT) and takes you through a series of implementation steps for each of the four pivotal learning areas: child motivation, responding to multiple cues/stimuli, child initiations, and self-regulation. PRT has primarily been researched and developed by Drs. Robert and Lynn Koegel at the University of California, Santa Barbara and Dr. Laura Schreibman at the University of California, San Diego. See the module references and resources section for a more complete list of contributors.

EBP Overview

![]()

After reviewing this overview section, you should be able to answer the following questions about this practice:

What is Pivotal Response Treatment?

Why use Pivotal Response Treatment?

Where Can You Use Pivotal Response Treatment?

What is the Evidence-base for Pivotal Response Treatment?

What is Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT)?

![]()

Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) is a naturalistic intervention based on the principles and practices of applied behavior analysis (ABA) and developmental approaches. PRT shares many instructional practices found in other well-researched, naturalistic behavior interventions, such as incidental teaching, enhanced milieu teaching, and naturalistic aspects of applied verbal behavior therapy (Allen & Cowan, 2008).

- PRT focuses on improving children’s motivation during learning and socialization (Koegel et al., 2006).

- PRT improves core behaviors, such as social communication, and is ideal for use with toddlers with ASD.

- PRT is also a child and family-centered intervention and capitalizes on child interests and initiations in everyday environments and within daily routines. It is particularly helpful for improving communication, language, play, and social behaviors.

Motivation may be the central pivotal area. Creating motivational PRT opportunities provides the foundation for implementing the other pivotal areas, as well as improving specific meaningful goals and objectives.

Select a pivotal learning area to read more:

Key Features and Guiding Principles of PRT

Select a link below to read more:

Select a link below to read more:

Naturalistic Teaching

Use naturalistic teaching to improve developmentally appropriate skills.

When the motivational components of PRT are combined, children are taught through social interactions that are as close as possible to more typical learning experiences. Parents and practitioners target pivotal areas and specific developmentally appropriate skills:

- in naturally occurring contexts (e.g., taking turns during play, during daily routines in “everyday settings” at home and in the community)

- with natural stimuli (for example, favorite toys or activities, more typical and varied instructional antecedents, varied learning opportunities or tasks)

- with natural change agents (For example, parents, siblings, respite workers, center-based educators, and practitioners)

- with natural contingencies (For example, loose teaching contingencies based on reinforcing attempts; using natural/direct reinforcers; contingent recasts of child communication, Koegel & Koegel, 2012.)

Skills or behaviors selected are developmentally appropriate and individualized, and developed in collaboration with parents and team members.

What specific behaviors or skills are targeted in PRT for infants and toddlers?

|

|

|

For more information related to naturalistic teaching, see the Naturalistic Intervention learning module and Allen and Cowan’s (2008) chapter on naturalistic teaching procedures.

Target Pivotal Areas

Target pivotal areas, particularly the toddler’s motivation to learn and engage.

Pivotal areas are suspected, through research, to produce a wider range of changes (e.g., collateral effects) compared to teaching many skills in isolation, one right after another. Also referred to as pivotal responses, pivotal behaviors, and/or behavioral cusps, pivotal areas cause a “ripple effect,” whereby a direct improvement in a pivotal area can lead to indirect improvements in many other skills.

Focus on positive child and parent affect

PRT components can improve toddler happiness, interest, enthusiasm, and overall

behavior.

Learning and interaction should be fun! These improvements help make PRT an acceptable and feasible intervention for parents and practitioners to implement. By implementing PRT motivational components, toddlers are learning and they are enjoying social interaction and intervention more often. Likewise, active parent involvement in interventions improves parent affect and confidence, and decreases parent stress (Brookman-Frazee, 2004). Positive affect is “contagious” in that happy and engaged toddlers can lead to happy and engaged parents, which in turn increases and maintains the toddler’s positive affect, and so on. It is important that sessions are conducted in a way that is fun and interactive for both toddlers and parents. PRT motivational components contribute to improving child and parent affect.

Educate, coack, and empower parents, family members, and practitioners or teachers

Significant individuals in the toddler’s life, particularly parents, are the primary

individuals carrying out PRT throughout the toddler’s day in natural, everyday

environments.

Educating and coaching parents is interactive in PRT, and involves a combination of didactic instruction, modeling by the clinician, practice by the parents, and immediate “live” feedback from the parent educator. This means that, during parent education sessions, both parents and practitioners are working together in a collaborative manner with a toddler. Variations of this PRT parent education model exist (Steiner, Koegel, Keogel, & Ence, 2012). For instance, group parent training formats and self-directed DVD parent training programs in PRT can also be used successfully. However, it is essential that parents and practitioners actively practice the techniques while receiving on-going feedback.

Emphasizing collaboration and parent empowerment, PRT parent education sessions incorporate parental expertise in setting up their toddler’s program (e.g., planning the toddler’s goals/objectives) as well as implementing the intervention. For example, parents help to pick out toys or what words to teach to the toddler during play. Many parents can obtain a high degree of confidence, reduced stress, and high levels of treatment fidelity (i.e., they can implement PRT well) through this approach. This parent education model is a cornerstone to PRT, but can apply to various natural change agents, including early childhood educators, practitioners, respite workers, siblings, and relatives.

Why Use PRT?

![]()

The potential advantages of using PRT over more traditional models include:

- increased generalization of acquired skills

- increased spontaneity and independence

- efficiency through collateral effects and “around-the-clock” implementation

- child- and family-friendly techniques that can be feasibly implemented

- improved engagement, behavior, and child affect during intervention

- improved parent affect and decreased parent stress

Koegel & Koegel, 1995; Koegel & Koegel, 2006

Where Can PRT Be Used and By Whom?

![]()

As a naturalistic intervention, parents and practitioners apply PRT in everyday settings, throughout the toddler’s day, during daily routines, and play. PRT has been evaluated in home, clinic, and community settings, with a variety of natural change agents. Teaching in varied everyday environments, by natural intervention agents such as parents, has been demonstrated to promote generalization and maintenance of skills. Emphasis on rapid generalization is an important facet of PRT.

Examples of specific settings at home and in the community:

- Morning routines

- Meal and snack times

- Play at the park

- Going for a walk

- Shopping at the mall

- Eating at a restaurant

- Bath time routines

- Bed time routines

- Play time with siblings

- Transitioning from one activity to the next (e.g., driving around town)

- “Mommy and Me” groups

- Family occasions

- Watching toddler TV programs

- Playing toddler games on the iPad

- Daily chores (e.g., laundry)

What Is the Evidence-base for PRT?

![]()

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC on ASD) initially reviewed the research literature on evidence-based, focused intervention practices in 2008. A second, more comprehensive review was completed by NPDC in 2013.

- A total of 27 EBPs are identified in the current review.

- Of the 27 practices, 10 practices that met criteria had participants in the infant and toddler age group, thus showing effectiveness of the practice with infants and toddlers with ASD.

The practices were identified as evidence-based when at least two high quality group design studies, five single case design, or a combination of one group design and three single case designed studies showed that the practice was effective. The full report is available on the NPDC on ASD website.

PRT meets evidence-based criteria with 1 group design and 7 single-case design studies. For the infant and toddler age group,one group design study included toddlers with autism and demonstrated positive outcomes in training parents in the use of PRT (Nefdt, et al., 2010). PRT can be used effectively to address soail, communication, joinrt attention, and play skills. A complete list of the research evidence-base literature for children aged birth to five is included in the Module Resources section.

Studies have been conducted for individual components of PRT, for the entire multi-component intervention, in multiple contexts, and for multiple ages and target behaviors. However, it is important to note that the development of this infant/toddler module extrapolated from PRT studies on slightly older children, as well as clinical expertise and very recent data on PRT for infants and toddlers. See References for a list of relevant studies, chapters, books, and websites.

Refer to the PRT Fact Sheet from the updated EBP report for further information on the literature for prompting procedures.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What are the four pivotal areas of pivotal response treatment (PRT)?

Question:

What are some advantages of using PRT?

Implementation Steps

After reviewing this section, you should be able to recognize the basic steps for using this practice.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

The planning process for PRT involves identifying objectives for the toddler, collecting baseline data, and preparing materials and activities.

Step 1.1 Develop meaningful objectives

The first step is to develop goal areas and specific objectives. In developing goals and objectives, take into account the toddler’s needs, strengths or interests, and family preferences, values, and context.

a) Identify the toddler's needs through direct observation, interviews, and

assessment

In PRT, the identification of child needs is based on the integration of observational data in everyday environments, interviews and collaboration with parents, and assessments. Generally, goals should address core areas of autism and developmentally meaningful behaviors through improving a toddler’s motivation to acquire and engage in the target behaviors.

There are no prescribed assessments, and it is not necessary to have formal assessments and testing complete in order to start PRT. Assessments might include, but are not limited to:

- Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale,

- Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (one word expressive and receptive)

- Child Development Inventory.

More intensive assessments, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale (ADOS), could also provide important information on specific target behaviors. Behavioral assessments, such as functional behavior assessments (FBA), provide valuable information regarding the child’s functional communication and challenging behavior. Further, assessments should be strength-based (Cosden, Koegel, Koegel, Greenwell, & Klein, 2006). PRT researchers and clinicians suggest that standardized assessments might reflect performance issues related to motivation, rather than ability levels.

Strength-based Planning for Infants and Toddlers provides some examples of the potential for strength-based, naturalistic assessment for toddlers with autism.

Always directly observe the infant or toddler and collect baseline data within natural, everyday environments and during child interactions with both parents and practitioners.

Semi-structured language and play samples (examples provided below), which collect a variety of information on the child’s communication, language, and behavior during play and daily routines, provide important information necessary to develop the toddler’s PRT program related to communication, socialization, and language. Direct observation and collection of baseline data on meaningful target areas, such as social interaction, joint attention, imitation, play, and interfering behaviors should inform your target goals and objectives.

In order to establish pre-intervention levels of a toddler’s motivation to learn and engage in developmentally appropriate behavior, initial and ongoing data collection should be collected by the interventionist to evaluate how responsive the toddler is to the social environment, how often the toddler initiates interactions (and the function of the initiations), and the toddler’s overall affect across contexts.

A Likert Scale can be used to monitor the toddler's affect. Included also are examples of possible meaningful goal areas that can be used when developing a PRT program for a toddler or an infant.

Monitoring Toddler Affect Using a Likert Scale

Monitoring Toddler Affect Using a Likert Scale

Possible Meaningful Goal Areas for Infants and Toddlers

Possible Meaningful Goal Areas for Infants and Toddlers

b) Develop meaningful communication and language objectives

Language or communication samples can help parents and practitioners assess communication in a toddler. The data gathered from language samples are individualized. This type of data would likely have to be scored from a video, or by another person than the person interacting with the toddler. For each opportunity to communicate or each initiated communicative act (numbered 1, 2,3...):

- an antecedent is noted (i.e., what happens before the communicative behavior?),

- what the verbal communication sounded like (and whether it was a new acquisition word, or an easy maintenance word?),

- what the function or purpose of the communication was, and

- where and with whom the communicative act occurred?

Nonverbal (prelinguistic) communicative behavior can be assessed in conjunction with verbal behavior, or by itself if that is an appropriate mode of communication for the infant or toddler. It is also important to note the duration of your sample.

Review an example oortion of an language sample

Review an example oortion of an language sample

Consider the suggested questions to ask about an infant or toddler's social-communicative behaviors. What data can be collected from the language sample?

c) Develop meaningful play, social engagement, imitation, and behavior

objectives

PRT targets social communication and language in the context of play, functional engagement in daily routines, and social activities. The development of social communication within PRT relies on the continued development of other developmentally meaningful areas, including expansion of the toddler’s preferences and play skill repertoire, increased attempts at spontaneous imitation of functional actions, and increased social engagement (including joint attention).

While using PRT, you will monitor challenging behaviors, such as stereotypical behavior and tantrums, but may not initially focus intervention here (unless the behaviors are particularly interfering and dangerous). Instead, the effort is placed on improving motivation during learning opportunities and interaction, and increasing functional communication, so that challenging behavior becomes less relevant to the toddler.

As a toddler’s motivation, functional communication, and functional engagement improves during the initial stages of PRT, many challenging behaviors may indirectly decrease. Still, the initial PRT plan should define the challenging behaviors and implement a functional behavior assessment in order to determine the behaviors’ functions, or the purpose they may serve for the toddler.

PRT continuously and proactively teaches communication that is functionally equivalent to challenging behavior, thereby helping to prevent further development of challenging behavior.

Step 1.2 Incorporate specific toddler and family factors in goal development

Incorporate the toddler's strengths, interests, as well as family preferences and values, into the development of goals and objectives when planning PRT. It is important to identify areas of need as well as the strengths of the toddler. PRT researchers and clinicians recommend a strength-based, naturalistic approach to assessment and intervention. Strengths should be capitalized on when developing goals, objectives, and intervention plans.

Review examples of strength-based assessment and intervention planning for a toddler

Review examples of strength-based assessment and intervention planning for a toddler

EXAMPLE: If a non-verbal toddler sometimes shouts out labels in a favorite TV show, this is where communication or language intervention might begin.

Developing the intervention plan should also focus on the contextual fit of the intervention objectives and the family’s needs. Instead of simply requiring a family to adapt to the intervention procedures and goals, make explicit efforts to adapt the intervention to various family contexts. Families differ in many ways, and goal development should attempt to fit into differing family contexts.

For instance, if a family has a newborn on the way, the play objectives may change to increasing independent, functional play (or play with an older sibling), instead of increasing turn taking during social games with a parent.

Step 1.3 Collect baseline data

Remember to take baseline data on the selected objectives and analyze the data.

Typically, 6-10 meaningful objectives are formally targeted at a time (where data are collected), but multiple other goal areas are still addressed and maintained. PRT implementation is not limited to those specific, formal objectives. You may capitalize on incidental learning opportunities that target different behaviors than the ones established in the formal objectives.

Taking baseline data will help you verify that the objective is necessary. You also will be able to compare intervention data to the baseline data in order to answer whether the intervention was effective. This, in combination with monitoring fidelity of implementation, allows for data based decision-making.

Step 1.4 Plan when opportunities will occur and prepare materials

PRT is intended to eventually become a part of the toddler family’s lifestyle. When this occurs, provide opportunities quite naturally, with minimal formal preparation. This is also the case in home and community settings. At first, you may benefit from some explicit planning and preparation. Even as PRT becomes a more natural occurrence throughout the day, continue to engage in some level of planning and preparation, particularly as new objectives and activities are introduced.

a) Create an inventory of motivators through various reinforcer and preference

assessments

This inventory help you provide more motivating items and activities during intervention and throughout the day. Make sure to follow the toddler’s lead and provide choices between these preferences in the moment. Although you may expect the toddler to engage in the most preferred activity, in the moment they may choose a different activity. You may be surprised at how many items and activities a toddler enjoys!

Planning Considerations:

What are the toddler’s learning strengths and emerging skills?

How can the toddler’s individualized PRT program capitalize on them?

Example ideas of motivators for toddlers:

Example ideas of motivators for toddlers:

- objects, items, and toys

- actions and physical activities

- social activities (where other people are an important part of the activity!)

- sensory activities (including stereotypy; non-functional, repetitive activities)

- snacks, meals, and drinks

- daily routines and actions

- places to go

- topics, themes, shows, characters

b) Continue to have toddler’s learning strengths and emerging skills in mind as

your prepare the materials

If the toddler is great at reciting the ABC’s, then this might indicate a strength and learning preference. If you are going to introduce some puzzles during play, ABC puzzles might be a great place to start. It might mean that the toddler learns well from repeated patterns and/or songs. If you initially select to teach functional, spontaneous verbal communication to a toddler, you might start by using carrier phrases within the alphabet or within a song. It is important to consider the toddler’s developmental level when selecting motivating activities and materials.

A practitioner might start singing, “A, B, C, ___” and then wait a few seconds for the toddler to say “D” before singing and pointing to the letter D. The practitioner could then plan to use other carrier phrases, such as “ready, set, __” and “one, two, three, __.”

c) List out the daily routines

These routines might differ by weekdays versus weekends, winter days versus summer days, etc. Remember to include the mundane!

Parents and practitioners often find that the best learning opportunities occur among the basic day-to-day events or items a toddler desires. These might include opening the door to go outside and play, buckling a seat belt to drive to the park, turning on the bath tub water before a bath, and turning a light on and off upon entering and exiting a room. Daily routines may provide excellent times to present motivating learning opportunities, as long as the toddler indicates that he or she wants these things to occur in the moment.

d) Decide what parts of the routine can be used to target the toddler’s meaningful

objectives and how the toddler’s interests and preferences can be incorporated.

After listing the various daily routines and activities, form an activity matrix of what objectives can be targeted during the different times of the day. Consider whether a particular time of the day should be dedicated to more intense intervention sessions with more frequent opportunities provided.

Prepare materials.

Once you have identified what types of interests and preferences the toddler has, and have planned where opportunities can be provided, the next step is to prepare any materials.

Consider the environmental arrangement.

Can the materials be arranged to gain shared control and establish motivation? For instance, a parent might prepare by putting the different colored ducks up on a shelf, in sight but out of reach in the shower, or put the ducks in a “locked” Tupperware container. Preparing materials is also about preparing to manage the materials.

If you are working on accurately requesting colors and the toddler enjoys playing with ducks in the bath, then prepare multiple colored ducks to have out during bath time. A toddler can even help paint them or select them at the store! In summary, you should use an activity matrix to help you plan when opportunities will occur and then prepare your materials and activities.

Practice Scenarios: Planning PRT

We recommend that you continue with the same Scenario setting throughout the module

Review the Troubleshooting Tips if you are having trouble viewing.

Knowledge Check

Question:

Which of the below is the most complete and accurate sequence of planning PRT for toddlers?

Planning PRT Sequence 1:

Decide on the skills to target based on an established curriculum and standardized assessment protocol, write measurable and observable objectives, collect baseline data, plan when the opportunities will be provided, and prepare any materials.

Planning PRT Sequence 2:

Decide on the skills to target based on direct observation, write measurable and observable objectives, collect baseline data, plan when the opportunities will be provided, and prepare any materials.

Planning PRT Sequence 3:

Decide on the skills to target based on direct observation and collaboration with parents, any assessments that have been completed, developmentally appropriate and meaningful areas (including core ASD characteristics) that are likely to produce immediate a widespread positive changes, strengths and preferences/interests of the toddler, and family preferences/context. This is followed by writing measurable and observable objectives, planning when the opportunities will be provided, and preparing any materials.

Planning PRT Sequence 4:

Decide on the skills to target based on direct observation and collaboration with parents and other practitioners, any assessments that have been completed, developmentally appropriate and meaningful areas (including core ASD characteristics) that may produce immediate a widespread positive changes, strengths and preferences/interests of the toddler, and family preferences/context. This is followed by writing measurable and observable objectives, collecting and analyzing baseline data, planning when the opportunities will be provided (and by whom), and preparing any materials.

Step 2 Implementing PRT

![]()

This step puts together individual PRT components to create a PRT learning opportunity. The steps for using PRT include selecting target behaviors and varying tasks and responses.

Step 2.1 Select target behaviors

Select your targets from the toddler’s individualized goals and objectives.

a. Determine the specific responses to prompt

Vary tasks. While following the toddler’s lead, parents and practitioners should vary tasks, materials, and activities to maintain their toddler’s interest and engagement. Mix up the activities and the tasks within activities. You should be alert to a toddler’s behavioral cues (e.g., lack of attention, attempts to change activities) that signal that they are becoming bored and that it is time to change to a new item or activity, or change the tasks and demands within an activity. It is best to vary the task before the toddler disengages, so that motivation can be sustained.

Target response variation. If appropriate, mix up the skills. Varying the target responses helps maintain a toddler’s level of responding and initiating during learning interactions. Varying targeted responses also helps avoid “drilling” the toddler. If attempting to improve a toddler’s motivation to engage socially and learn, avoid drilling by varying the target responses. Again, be alert to a toddler’s behavioral cues that signal that they are becoming frustrated or bored and that it is time to vary the targeted responses.

Mix up the instructional cues, prompts, and contexts. Increasing the variation in cues and prompts for a task, and other environmental conditions, also helps to link desired responses to a variety of antecedents and contexts that could be present in a toddler’s everyday environments. An example would be: teaching colors on a variety of child preferred stimuli during a variety of games in different rooms of the house. This increase in variation allows for the possibility of greater spontaneity and generalization beyond the initial learning situations and fosters the toddler’s responsiveness to a range of stimuli.

b. Intersperse maintenance and acquisition tasks

You can maximize a toddler’s motivation during learning and interaction by mixing maintenance opportunities with acquisition opportunities. The acquisition trials involve tasks that are new or currently being learned and are often times more difficult trials than previously mastered items in maintenance trials.

Identify

Identify skills that are easy for individual toddlers (i.e., maintenance tasks) and ones that are more difficult (i.e., acquisition tasks).

Mix

Provide a mixture of easy and more difficult tasks so that toddlers can be successful at using a variety of skills.

Build momentum

To facilitate maintenance of previously learned target skills and to build behavioral momentum for good trying on harder tasks, provide a few short requests that are easy and within the toddler’s current repertoire of mastered skills to complete followed by one or two requests that are slightly more difficult for the toddler to complete.

EXAMPLE

A parent might ask a toddler to point to a familiar picture in a favorite book (a maintenance task), then ask them to identify a less familiar picture, or perhaps by asking what is happening in the picture.

This is an acquisition task targeting verbs.

By attending to a toddler’s behavioral cues that signal that adding maintenance tasks prior to the next acquisition task might help optimize the toddler’s motivation to learn and socially engage, the ratio of maintenance and acquisition tasks can be varied.

The toddler's behavioral cues might include: lack of attention, avoidance responding, escape-driven challenging behavior, lack of trying, and indications of frustration.

Step 2.2 Identify learning activities and stimuli

a. Follow the child's lead

Following the toddler’s lead in order to identify child-preferred teaching materials or activities and natural reinforcers is an important component of establishing motivation in PRT. This step allows toddlers to choose play materials, toys, and activities that will be used in the PRT learning opportunity.

- Begin following the child's lead by observing when the toddler has free access to materials and activities to identify their preferences for items, activities, and toys. Entice the toddler with toys and activities and observe how they toddler responds in order to assess if, in that moment, they are interested in playing with the materials or engaging in the activity.

- If the toddler indicates interest in the moment, then the item or activity can be used within the PRT learning opportunity.

A toddler might indicate interest by reaching for the materials, begining and playing with the materials, or by smiling and giviing eye contact during the social activity.

EXAMPLE

A teacher notices that a toddler plays with dinosaurs for most of free play. The teacher follows the toddler’s lead by going over and playing with the dinosaurs together. By following the toddler’s lead and combining it with shared control, the teacher could intersperse PRT learning opportunities as they play with the dinosaurs.

Beginning learners, or younger toddlers, working on developing communicative intent could be prompted to vocalize “dino” or point to the “dino” in order to take a turn playing with the dinosaur. A more advanced learner, or older toddler, working on play skills such as block building could be prompted to build a tower together prior to letting a dinosaur knock over the tower.

b. Embed social interests and preferences

Identifying individualized, socially oriented reinforcers and embedding preferred social interaction within the delivery of natural reinforcement has been shown to improve social engagement and joint attention (Jones, Carr, & Feeley, 2006; Koegel, Vernon, & Koegel, 2009; Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman, & Stolen, 2012).

Why embed social activity interests and preferences?

These strategies may help increase social behaviors such as reciprocal social smiling, eye contact, social orientation toward a parent instead of toward an object, and joint attention. Some researchers suspect that early challenges in social motivation are core to the development of ASD (Dawson, Webb, & McPartland, 2005).

PRT can be used to increase social motivation early in an infant or toddler’s development before secondary symptoms arise (Dawson, 2009; Voos et al., 2013).

Preferred social activities:

- incorporate as activities more frequently in the child’s day.

- embed within natural reinforcers.

- use as an idiosyncratic social reinforcer as a consequence for joint attention.

It is important, especially for infants and young toddlers, that rewarding social activities comprise many of their PRT learning interactions. A rewarding social activity is an activity where another person, such as a parent, is a crucial component of the reward value associated with the activity. In other words, the reinforcer does not exist without the social engagement of the parent or practitioner with the toddler or infant.

Infant and Toddler Social Activities

- Being held and walking around together

- Peek-a-boo games

- Blowing on stomach to make silly noises

- Singing songs/rhymes with sensory actions (i.e., “This Little Piggy,” “Itsy Bitsy Spider,” and “Patty cake”)

- Jumping, bouncing (“Giddie-up horsie” on knee), swinging, spinning, and dancing together

- Going “night, night” games

- Fall down games

- Playing “airplane”

- Silly face games- such as, raspberry lips

- Silly noises/voices games (such as making animal sounds; making silly “sneezes”)

- Chase “I’m gonna get you!” games

- Tickle games

- Splashing water at each other

- Driving/pushing/pulling around in a wagon/sled

- Blowing bubbles

- Blowing up balloons and letting them go

- Juggling balls in the air

It may be the case that an infant or toddler’s involvement in social activities is restricted, minimal, and fleeting. Combining this step with Interspersing Maintenance and Acquisition, as well as the other motivational components, can help increase the duration and quality of engagement in social activities. Researchers and clinicians at the UCSB Koegel Autism Center have developed Five Steps for Building Early Developing Engagement in Social Activities. These are described below:

Five Steps for Building Early Developing Engagement in Social Activities

1. Identify social activities

Follow the infant’s lead and identify a variety of social activities in which s/he will engage – even if briefly! Parents and practitioners may have to do some enticing and “try outs” of the different social activities in different contexts. Be persistent and look for even fleeting moments of eye contact and positive affect, such as brief smiles. Categorize the social routines according to neutral or preferred activities. Parents may have different levels of preferred activities, such as, “sometime preferred” versus “often preferred.” Parents can turn the list into a preference hierarchy of social activities.

2. Incorporate preferred (maintenance) social activities only, and rapidly vary them

Begin with strengths! Start by incorporating the most preferred social activities in which the infant will usually engage. Spend 10 seconds on each preferred social activity before varying the task to the next activity. Do this for approximately 5 minutes or less. Start with smaller amounts of time and increase gradually. End each social activity on “a positive note,” when interest levels are still high. Do not wait until the infant or toddler has indicated lack of interest before varying the social activity.

3. Add a neutral (acquisition) social activity

Within the next few times a parent provides these opportunities, they should attempt to introduce the next social activity on the hierarchy list and add it to the activity repertoire. Intersperse it among the preferred maintenance social activity. For instance, engage in the social activity the infant/toddler is most likely to happily engage in (maintenance), and then vary the task by introducing the neutral acquisition activity while they are still engaged. Make the acquisition social activity very brief at first.

4. Reinforce and take frequent breaks

Reinforce the infant or toddler by quickly going back to the preferred maintenance social activity. Take a break after the designated amount of time for staying socially engaged in social activities (e.g., 5 minutes total). Remember, these simple social interactions could be taxing on an infant or young toddler. Try to choose social breaks, such as being carried around by an adult, but make sure it is a break!

5. Gradually increase

Gradually increase the duration of each social activity, the overall amount of time socially engaged (e.g., from 5 minutes to 7 minutes), as well as the number of social activities added to the infant or toddler’s preferred social activities.

Incorporate into PRT opportunities at a later time. As the infant or toddler develops, embed the preferred social interactions into natural reinforcers for other PRT opportunities. For instance, as the infant or toddler begins to prefer the tickle activity, intersperse prompts to vocalize “tickle” and naturally reinforce attempts by tickling the infant or toddler.

(Koegel, Singh, Koegel, Hollingsworth, & Bradshaw, 2013)

See Natural Reinforcers, for more on embedding social activities in natural reinforcers and using individualized social reinforcers.

EXAMPLE

A mom observes that her 9-month-old rarely socially smiles, however sometimes likes being held and walked around, having her toes nibbled, and having her stomach blown. Her infant, though, will only play peek-a-boo for very fleeting moments and will almost never socially smile during the routine. Mom wants to increase her infant’s social engagement during this peek-a-boo activity. Mom begins the social play routines at a time she has found her infant to most likely respond with eye contact and smiles, which happens to be right after bath time. Mom quickly varies between nibbling on her toes and blowing her stomach, and after a few minutes (before her daughter disengages), mom picks her up and walks around the room together. Mom continues this all week.

After a few days her infant is consistently giving eye contact and socially smiling, and sometimes laughing during these brief social routines. Mom then decides to add peek-a-boo to the routine. After going through the maintenance social activities, mom begins playing peek-a-boo and as soon as her infant responds by looking at her with a smile, mom smiles back enthusiastically and goes back to blowing her stomach. A couple days later, mom mixes in two peek-a-boos because her daughter is spending more time happily and socially engaged during the ten seconds of peek-a-boo. This interaction becomes a part of their bath time routine. Soon her infant is anticipating the peek-a-boo game after her bath. Later in her child’s programming, when she is 13 months and highly prefers peek-a-boo, her mom prompts her to say, “boo,” in order to initiate playing peek-a-boo together.

c. Incorporate interests and preferences

You may also incorporate a toddler’s interests into established or new activities, tasks, and routines. For instance, if the toddler has a perseverative or strong interest in dinosaurs, during the play dough center, the dinosaur cookie cutters could be used to motivate the toddler to play functionally with the play dough. A toddler working on receptive language skills and functional play could be told to either roll the play dough or pat down the play dough. Making dinosaurs with the dinosaur cookie cutters naturally reinforces the toddler’s attempts. During book time, books with dinosaurs could be read together and PRT opportunities could be interspersed during the engagement (e.g., asking the toddler, “What do you see?” and then naturally reinforcing them by turning the page to see more dinosaurs).

EXAMPLE

A mom wants her older toddler to wash her hands, but often refuses and tantrums. Mom decides to incorporate her interests, including bubbles and letters. Mom fills up the sink and makes bubbles and puts plastic letters in the sink. As her toddler begins to accept going to the sink to wash her hands, mom gradually fades out the bubbles and letters.

Arrange the toddler’s environment with child-preferred, developmentally appropriate objects and activities. During free time a parent could lay out an array of art materials for a toddler who enjoys arts and crafts.

d. Provide choices

Incorporate choice-making opportunities into naturally occurring routines, activities, and task demands or instructions throughout the day. Choices enhance engagement, increase rates of learning, and decrease challenging behavior. Choices also provide outstanding communication and language development opportunities.

EXAMPLE

A ball, a clear box of blocks, a shape sorter, and a bottle of bubbles can all be placed on a high shelf, in sight, but out of reach. When the toddler points to the bottle of bubbles and says an approximation of “bubbles,” the parent can say, “blow bubbles!” (a recast) and take them down and start to open them with the child (the natural reinforcer). The toddler had the choice of several different objects, each providing an equal opportunity to practice communicating through requesting items. For an older toddler with more language skills, you might ask, “Do you want to play more ball or go on the slide?”

Choices are also provided within adult-directed instructions, providing a level of shared control (see Shared Control) that improves a toddler’s response to adult direction. A variety of choices can be offered in terms of: what / which (what to do, which one to play), where (to do the task), with whom (to play), how (the action should be done), and when (to do the activity).

EXAMPLE

During a transition away from a preferred activity such as trampoline, a practitioner could ask the toddler if she wants to run inside or walk to the swing, or if she wants to jump five more times or ten more times before going inside for snack. If it is time to work on fine motor skills and scribbling with crayons, the toddler could choose which color crayon or paper to use.

Allow toddlers to select materials, topics, and toys during teaching activities. This may be particularly important when introducing new skills and tasks. Using toys, items, and activities that individual toddlers prefer may increase their motivation to participate and thus may increase the likelihood that they will rapidly acquire target skills and use them spontaneously. For example, when a toddler chooses to use colored Legos instead of wooden blocks, he may be more motivated to complete a tower building task during fine motor center.

Examples of Incorporating Perseverative Interests to Increase Joint Attention |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Perseverative Interest |

Puzzle |

Pretend Figurines |

Books |

|

Numbers |

Number puzzle |

Draw numbers or put number stickers on existing figurines |

Counting and number books |

|

Opening and closing various doors |

Wooden board with different doors and latches to open |

A doll house or barnyard set with various doors |

An interactive book that has flaps hiding pictures and text (flaps that can be open and closed) |

|

Animals |

Zoo animal puzzle |

Barnyard play set, animal figurines |

Zoo books |

|

Vehicles |

Vehicle puzzle |

Miniature vehicles with ramps/garage |

Car books |

Step 2.3 Establish motivation through shared control and turn taking

Creating shared control is an important step in establishing the toddler’s motivation to respond. Shared control also assists in obtaining the toddler’s attention. The concept of shared control generally has to do with both the adult and child playing important roles in the learning interaction. Shared control also helps to set up, or establish, a situation where natural reinforcers can be provided contingent on attempts at target behaviors (see Natural Reinforcers). Sometimes this is called briefly “restricting access” to a child chosen item or activity.

Ways of creating shared control in order to increase a toddler’s attending and establish a toddler’s motivation to interact and try during the learning opportunity:

Take turns

Turn taking is a natural way to set up a contingency and provide appropriate models. Once parents and practitioners have established that the toddler is interested in engaging with a certain item or in a certain activity in the moment, then they are ready to set up shared control. By taking a turn, parents and practitioners are not only teaching the toddler turn taking, but also setting up an opportunity for another learning interaction, whereby the toddler is given another turn contingent on an attempted response (see Natural Reinforcers). Appropriate models (e.g., play actions and comments on play) are also provided on the parent or practitioner’s turn.

Manage materials and "in-sight and out-of-reach"

Have child-preferred materials in a container or kept in-sight of the toddler, but out of their reach. The chosen materials are brought out one at a time and piece by piece. This allows for shared control of the materials. The adult controls the flow and delivery of the toddler chosen items and activities contingent on desired response attempts by the toddler. This environmental arrangement helps establish motivation throughout play or a daily routine.

Create (or wait for) opportunities where the child needs adult assistance

Parents and practitioners are good at knowing when a toddler needs assistance and may complete the assistance without expecting a response from the toddler. Instead, in PRT they create shared control and use these times as learning opportunities!

Interrupt a routine

Interrupt a routine and complete the routine contingent on a desired response by the toddler is another way to establish motivation through shared control. Instead of the toddler having full control over the routine, a practitioner and toddler share control of it. If possible, interruption should be natural and playful, versus abrupt and overly contrived.

Break up natural reinforcers and provide “bit-by-bit”

Break up learning stimuli and natural reinforcers, and provide just a bit at a time, thus allowing for more opportunities to create those motivational shared control situations

Provide choices in selecting an activity and which parts of a task the toddler

might complete

Shared control learning interactions also involves providing choices in activities and tasks. For instance, although at first the toddler’s interests will be followed, they will likely be followed within appropriate boundaries set by the parent of practitioner. As seen in prior examples, the parent or practitioner also chooses what responses are expected of the toddler during PRT learning opportunities. Further, as an older toddler progresses, it may be the case that the parent or practicioner and the toddler take turns in choosing among preferred and neutral activities. Within a given task demand, there also may be shared control over which parts of the task or routine will be completed by the toddler versus the parent or practitioner, or how the task will be completed.

Step 2.4 Get the toddler's attention

Parents and practitioners should establish the toddler’s attention before providing cues, prompts, questions, instructions, and/or choices (see Prompting Strategies). Strategies for gaining attention include: saying the toddler’s name, tapping on their shoulder, making an enthusiastic sound or phrase, giving a quick tickle, making eye contact, and/or arranging the environment to support shared control (see Shared Control). Strategies for gaining a toddler’s attention should also be varied over time.

Individualization: Orienting cues and nonverbal toddlers

Some toddlers who are nonverbal may have difficulty orienting and attending to the relevant cues in the learning interaction, such as, a verbal model of a word. In this case, effective and individualized strategies for gaining child attention/orienting should be tried (Koegel, Shirotova, & Koegel, 2009).

Using individualized orienting cues just prior to providing the verbal model prompt could improve the beginning learner’s response to the verbal model prompt, that is, imitation of the verbal model.

EXAMPLE

A three-year-old nonverbal toddler who had difficulty developing first words, oriented to and imitated the verbal model immediately after being asked to give a high-five.

High-fives were found to consistently produce an orienting response from the three-year-old. The researchers thought that the high-five functioned to orient the child to the relevant information: the adult’s verbal model of the word.

Step 2.5 Use clear, natural, and varied prompts

Once the toddler is attending, parents and practitioners use brief and clear instructions. These instructional antecedents should mirror naturally occurring cues and prompts as much as possible.

EXAMPLE

When a toddler indicates he wants to turn the water on at the sink, a parent or practitioner can teach the toddler to request to turn it on (when the toddler has not yet acquired the word “water”) by prompting the toddler simply with the verbal model, “water.” There is no need to prompt with, “Say water.” Likewise, saying a long phrase, such as, “Okay, Logan, just say water!” is not an appropriate instructional antecedent for teaching first words with PRT.

The most commonly used PRT prompting strategies, or instructional antecedents, from most assistance to least assistance, and from least independent to most independent, are:

- model prompts

- chioces

- open-ended questions or statements and

- time delays.

Model Prompts

The full model is used to prompt the child to respond with an imitation of the model. In order to increase rapid independence, partial prompts can be used to fade full models.

Choices

Providing choices is another motivational procedure (see Step 2.2 for more on choices) and is an important prompting strategy. Choices contain two models for the toddler to choose between and can prompt the toddler to imitate one of them (and not the other) and/or engage in one of the response choices (and not the other). Careful and systematic teaching of choices is also useful for reducing immediate echolalia and indiscriminate choice making (e.g., the toddler simply repeats the last part of the choice). See Koegel and Lazebnik (2004, pp. 56 - 59) for simple solutions for reducing immediate echolalia and increasing accurate choice making in verbal children with autism.

Open-ended questions or statements

Open-ended questions, such as Wh- questions can be immediately faded into prompting strategies as the toddler acquires various words or communicative acts. If a toddler already asks to go outside by approximating the word “outside,” a model prompt is not necessary. A choice, question, or time delay will help a toddler become more spontaneous with their communication. Example questions could be, “What do you want?” or “Where should we go?” or “What would you like to do?”

Be careful providing too many close-ended questions that result in yes or no answers, unless this is a specific objective. These yes or no questions limit the toddler’s chances of practicing more meaningful and varied verbal skills. You can also make open-ended statements that would prompt a different but similar statement or a question from the child. For instance, upon taking the letter puzzle piece “A” from a container, you say, “I got A!,” which provides a verbal cue for the toddler to say, “I got [ the letter the toddler picked ]!” when they take a letter on their turn. Similarly, you can take a letter and hide it in their hands, and say, “I got a letter!” as an opportunity for the child to ask, “What letter?”

Time delays

Time delay prompts involve minimal immediate actions on the part of the parent or practitioner. Time delays involve waiting for a brief period (e.g., 3-5 seconds) prior to providing more assistance. For instance, if the toddler wants his father to roll the ball back to her, and the father has been providing the model “ball” to prompt the request, the father might instead pause and wait expectantly for a few seconds. If his toddler says “ball” independently during that pause, the father should roll the ball back as he recasts, “roll ball!” If his toddler does not respond, then the father can provide more assistance by: modeling the word, asking if he should “roll ball or roll car,” (while showing each option) or simply asking her what he should roll, “What should I roll?”

Step 2.6 Immediately reinforce the toddler's attempts

a) Reinforce the toddler's attempts at responding that are clear, unambiguous, and goal-directed.

Reinforcement of response attempts is a consequence PRT component brecause it happens after the toddler provides a response. Reinforce the toddler's attempts that are purposeful approximations of the targeted response. By reinforcing attempts, in addition to correct responses, you increase the likelihood that children will engage in future attempts as they experience more success and positive reinforcement for appropriate trying. Learning to talk, play, and socialize can be hard work, and reinforcing attempts may keep toddlers willing to engage in the “hard work.”

EXAMPLE

A nonverbal 18-month old who is starting to make erbal communicative intent, reaches for a book and says, “Ooo!”

Although this is not the targeted response, such as, “book”, the parent immediately reinforces the attempt by saying “book!” while handing the book to the toddler.

Doing so naturally reinforces the attempted vocalization and re-models (recasts) the target response.

b) Provide direct reinforcement immediately after a goal-directed attempt

Provide direct reinforcement immediately after and contingent on a goal-directed attempt. Pay careful attention to providing reinforcement only after a correct response or attempt by the toddler.

EXAMPLE

A practitioner immediately continues tickles (the natural reinforcement) for an infant who attempts social engagement by giving brief eye contact and socially smiling.

Step 2.7 Use direct or natural reinforcers and then transition to the next opportunity

A natural reinforcer is defined as a reinforcer that has a direct relationship to the child’s behavior and the task. The reinforcer, a consequence, is logically related to a chain of antecedents and responses.

EXAMPLE

A toddler may indicate interest in blowing bubbles. When he blows the bubbles, the bubbles created are the natural reinforcer for this behavior (i.e., blowing the bubbles). Likewise, if the toddler requests the bubbles to be blown by vocalizing, ”bah,” the natural reinforcer would be for the parent to open the bubbles and blow them (or help the child blow them).

a) Identify materials and activities that can be used to address a toddler’s

objective during a teaching opportunity

This is done in conjunction with following the toddler’s lead, providing choices, and establishing motivation through shared control. The delivery of the natural reinforcer is directly tied to these PRT components.

For example, a parent or practitioner presents a child with a clear jar with a lid that contains raisins. The toddler will most likely try to open the jar and then look to the practitioner for help. After the toddler attempts to use a target phrase either independently or through clear prompting, such as “help!” or “open raisins", the practitioner immediately provides access to the natural reinforcer inside the jar.

In contrast to PRT opportunities that employ natural reinforcers, the parent could have prompted the toddler to say “open” in reference to an empty jar, then provide a raisin sitting on a plate on the table.

b) Parents and practitioners implement a learning activity that is functionally

and directly related to the toddler’s objectives

If a toddler’s target behavior is to ask for a break instead of escaping demands by screaming, when the toddler initiates a request for a break by saying, “break” or pointing to a “break card,” the practitioner immediately responds by allowing the toddler to have a minute of neutral free time while staying in the same area. However, if the teacher instructed the toddler to complete another task before reinforcing her initiated response, “break,” then this would not be an example of a directly related, functional reinforcer.

Note: Although not a natural reinforcer, this would be an appropriate strategy for thinning reinforcement in order to increase desired task engagement over time.

c) Embed social interaction into natural reinforcers

Follow the infant and toddler’s lead in order to identify reinforcing social activities that can be increasingly incorporated into routines for infants and toddlers. Research has also identified that embedding preferred social activity into the delivery of the reinforcer is effective in improving synchronous toddler and parent engagement, eye contact, and improved toddler and parent affect (Vernon et al., 2012).

Potential Ways to Embed Motivating Social Activity into Delivery of Natural Reinforcers |

||

|---|---|---|

| Activity & child response (prompted or spontaneous) | Natural reinforcers without social activity | Natural reinforcers with embedded social activity |

| Jumping on trampoline Toddler requests, “jump” | Toddler gets to jump on trampoline | Adult jumps with the toddler |

| Splashing in the bath Toddler requests, “splash” | Toddler gets to splash water | Adult splashes the toddler, toddler splashes the adult |

|

Playing cars

Toddler says, “crash cars” |

Toddler is given two cars to crash into each other | Adult crashes a toy car into the toddler’s toy car |

| Sliding on slide Toddler says, “slide” | Toddler gets to go down the slide | Adult and the toddler go down the slide together |

| Music Toddler requests a song | Toddler listens to the song on the computer | Adult sings the songs to the toddler |

| Playing with dinosaurs Toddler communicates “dino” | Toddler is given a toy dinosaur | Adult “roars” the dinosaur and makes it “stomp” or “fly” over to the toddler |

d) Reinforce joint attention and social comments with individualized social

reinforcers

Joint attention is a triadic social experience between a child, item or event, and an adult. Infants as young as 8-months old engage in joint attention in order to share with parents their affect (interest, happiness, enthusiasm) associated with an event or item. The natural reinforcers for joint attention acts should be distinct from the natural reinforcers associated with requesting items and events, as well as other behavior regulation functions (Jones, Carr, & Feeley, 2006). Provide the enjoyable social reinforcers right after joint attention, such as pointing at a picture or saying a comment.

These reinforcers are:

(1) individually identified (and often unique) for each toddler and

(2) they are social.

They are social because the rewarding aspect of the activity centers around interaction with the adult.

Review examples below of potential ways to use social reinforcers when directly targeting joint attention in infants and toddlers. In the examples, the toddler’s social reinforcers include tickles, exaggerated noises or voices, and jumping with an adult.

Using Social Reinforcers as Natural Reinforcers forTargeting Socially Motivated Joint Attention Behaviors |

||

|---|---|---|

| Activity & child response (prompted or spontaneous) |

Example non-social reinforcers for: joint attention used for requesting objects |

Example of Idiosyncratic natural social reinforcers for: joint attention used for socially sharing affect |

|

Walking at the zoo Toddler points at a monkey and looks back at mom |

TToddler allowed to go look at the monkey |

Mom says, “Yes, a monkey!” gives the toddler “monkey tickles;” mom and child make monkey noises together |

|

Reading a book Toddler brings the train book over to mom, gives eye contact, and says, “trains!” |

Mom gives the train book and/or reads the book to the toddler |

Mom exclaims, “Choo! Choo!” and pretends to be a train while making train sounds |

|

Playing Pop Up Pirate™ Toddler points at the pirate, looks at mom, and comments, “it popped!” |

Mom gives the toddler more pirate swords to continue playing the game | Mom says, “The pirate popped!” and has the toddler on her lap, and bounces him as if to make him “pop up” |

|

Doing a letter puzzle Toddler finds the letter “V,” picks it up, holds it out to show Dad, and smiles at him. |

Mom gives the puzzle board to the toddler so they may put in the letter “V” |

Dad tickles the child while making a “Vvv” sound and says, “You found V!” |

|

Playing Cariboo™ Toddler opens a door with the key, points down, looks up at the practitioner, smiles, and exclaims, “pink ball!” |

Toddler may take out the pink ball and continue with the chosen game |

The practitioner juggles the ball while making silly noises, and says, “the pink ball!” |

Step 2.8 Target pivotal area of initiations

Using Child-Initiated Strategies: Teaching Question Asking

Toddlers with ASD can successfully be motivated and taught to ask a variety of Wh- questions (Koegel, Bradshaw, Ashbaugh, & Koegel, 2013). Question asking is particularly relevant to initiations because it shifts the initiation of the learning interaction from the adult to the child. Often times, adults ask all the questions and start most of the learning interactions. By asking questions independently, toddlers initiate interactions that facilitate information gathering and further learning. Teaching question asking also expands the purposes for which children might use communication.

The questions described in this section are in developmental sequence.

Step 2.9 Target the toddler's responses to multiple cues

Increase the toddler's responses to multiple cues

Using PRT motivational opportunities, teach and motivate older toddlers and preschoolers with ASD to respond to multiple cues. Cues, also called properties or attributes, are taught incrementally until toddlers respond to more complex tasks. Teaching multiple cues may not be appropriate for younger toddlers and are associated with advancing language and conceptual skills.

Identify multiple cues and gather materials with multiple cues. Parents and practitioners identify a variety of cues (properties or attributes) that are associated with the stimulus (e.g., toy) or activity and that can be used during a PRT learning opportunity.

Add another cue. As the older toddler advances, parents and practitioners provide at least two cues (e.g., overemphasizing feature of object, color, size, type of object, location of object) so that their toddler will begin to use the target skill in response to more than one cue.

Increase complexity. Parents and practitioners gradually increase the number of cues associated with a particular object, material, or toy so that the learner can respond to a variety of stimuli

Schedule reinforcement

Parents and practitioners also use different schedules of reinforcement to teach an older toddler with ASD to respond to multiple cues.

Identify natural reinforcers. Numerous natural reinforcers that can be used to increase a toddler’s motivation to use the target skill of responding to multiple cues. For example, a practitioner might notice that the toddler enjoys playing games on the iPad, including a balloon popping game.

Begin with fixed ratio, continuous schedule (i.e., FR1). Provide reinforcement for every attempt to use the target skill successfully (continuous schedule). As an example, a toddler is allowed to “pop a balloon” (natural reinforcer) on an iPad screen every time she answers what color or shape the balloon is.

Progress to variable ratio, intermittent schedule (e.g., VR2). It is important to progress to intermittent reinforcement schedules throughout an older toddler’s PRT programming. In a continuous schedule of reinforcement, you would allow the toddler to pop the balloons on the iPad game every time she responds to a question about the color or shape of the balloons she wants to pop. With a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement, VR2, the toddler responds with good attempts for an average of 2 questions prior to popping the balloons in the game.

Step 2.10 Target self-regulation

Use PRT motivational opportunities to teach and motivate children with ASD to engage in appropriate behaviors that foster early developing self-regulation skills. Implement self-management differently for older children. Refer to the National Professional Development Center on ASD for more information on Self-Management.

Below are strategies that are integral aspects of early PRT programs and designed to teach the toddler to regulate his/her behavior through appropriate communication rather than challenging behaviors.

Teaching “all done” and “break” to terminate activity and transition

-

Parents and practitioners teach the toddler to terminate an activity and transition by prompting them to communicate, “all done” prior to leaving an activity or areas. This can replace challenging behavior related to frustration and boredom that results in the toddler escaping the task. Or it may replace a toddler’s fleeting engagement as they bounce around from one activity to another.

-

When the toddler communicates “all done,” naturally reinforce the toddler by allowing them to leave the area/activity.

-

As the toddler learns to communicate “all done,” parents and practitioners add a clean up component that is brief at first and then gradually more involved. Clean-up occurs prior to allowing the toddler to leave the child-chosen activity.

-

When toddlers are happy to clean up, parents and practitioners target various skills during clean up and it may be the case that the toddler re-engages in the activity during clean up. Often this leads to increasing a toddler’s duration engaged in the same child-chosen activity.

-

As the toddler progresses, toddlers learn to terminate the activity by initiating “all done,” cleaning up, and then initiating play with a new activity with an adult (e.g., “come play…!”), prior to engaging in the new child-chosen activity.

-

Asking for a “break” is taught in a similar fashion, however breaks are limited to a brief termination in the activity followed by re-engagement in the same activity.

Teaching "help" to request assistance

Teaching children to request help can decrease challenging behaviors associated with frustration, avoidance of tasks, and escaping tasks. It is important to be careful of reinforcing challenging behavior by helping a toddler after they just engaged in a tantrum or similar challenging behavior. Prior to providing assistance, parents and practitioners prompt the toddler to communicate, “help,” using an appropriate mode of communication. This teaches the toddler to regulate his/her behavior through appropriate communication.

Replace challenging behavior with Functional Commuication Training (FCT)

PRT can be used to teach appropriate, functionally equivalent (but more efficient) communicative replacement behaviors. During PRT interactions, proactively replace challenging behavior by prompting and differentially reinforcing appropriate communication while placing challenging behavior on extinction (i.e., withdrawing the maintaining consequences when challenging behavior is exhibited.

PRT components also serve as antecedent (preventative) procedures by maintaining a toddler’s motivation and making challenging behaviors less relevant or necessary to the toddler.

Replace challenging behaviors that serve the following functions:

- obtain items or activities

- obtain attention

- avoid or escape task demands and attention

This strategy relies on the adult correctly identifying the function of the challenging behavior, and so the parent or practitioner may need to take data through a functional behavior assessment (FBA). However, clear functions can be actively replaced in the moment across multiple situations. Teaching the toddler to communicate to get his/her needs met is an important early developing self-regulation skill that can be fostered in toddlers. Differentially reinforcing functional communication at a young age could play an important role in the prevention of more serious challenging behavior from developing later in childhood. Combining FCT with the motivational components of PRT is an effective way to decrease interfering challenging behavior and keep children happy and learning during intervention and interaction.

Improve tolerance for delays to reinforcement. For functional communicative acts, it is also important to teacher older toddlers and more advanced learners to tolerate delays to reinforcement. The amount of time before receiving reinforcement for maintenance requests by the toddler can be gradually increased and the reinforcer can be provided contingent on appropriate waiting during the delay (e.g., absence of challenging behavior). Parents and practitioners introduce reinforcement schedule thinning by intermittently reinforcing maintenance behaviors.

Note: There are many positive behavior supports that should be integrated into a toddler’s intervention as needed. Other important techniques for addressing challenging behaviors in toddlers might include systematic desensitization, various antecedent manipulations, differential reinforcement of other behavior, additional applications of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior, and instructions based on the Premack principle.

Using Visual Activity Schedules and Systems

Teaching toddlers to use a visual schedule or activity system is another way to foster early developing self-regulation skills.

Practice Scenarios: Implementing PRT

Knowledge Check

Question:

Which of these represents a motivational opportunity for a nonverbal 17-month old toddler?

Select one of the following:

- A nonverbal child reaches for the light switch to turn on and off the light. A practitioner stops the child and redirects the child to vocalize for a ball he is holding. The child does not respond or attempt to obtain the ball and instead goes back over to the light and turns it off.

- When a mom sees her nonverbal child playing with a ball ramp game, she puts down the book she was going to read to him and goes over to the ball ramp toy. Mom repeatedly says the word “ball” while trying to get her son’s attention as her son continues to put the balls down the ramp.

- Dad notices his two-year-old nonverbal son keeps going inside the laundry basket and is avoiding playing cars with him. Dad goes over to the basket and picks it up and puts it down with his son inside. His son smiles and nonverbally indicates he wants more. Before picking it up, Dad gets his son’s attention and models “up,” and picks it up and puts it back down a couple of times in a row. The child still indicates he wants to go up again, but this time dad models, “up” and waits for the child to attempt to vocalize “up” before he lifts him up. After 3 seconds, the child finally says, “aah,” and dad immediately and enthusiastically lifts up the laundry basket while clearly and enthusiastically recasting, “Up!”

- A practitioner selects multiple flashcards of items she knows the three-year-old toddler prefers. She sits with her on the carpet in the playroom (the natural environment) and then provides ten trials in a row asking the child, “What’s this?” for each card. The child gets to briefly play with either a squishy ball or spin toy (determined through a brief reinforcer assessment) for correct responses.

PIVOTAL AREA: SELF-INITIATIONS

Question:

What are some potential collateral effects of self-initiations?

Question:

Which intervention uses an appropriate natural reinforcer for teaching question-asking?

Select one of the following:

- When the toddler asks where an item is, you go get the item and give it to the toddler

- When a toddler asks “Whose is it?” referring to a toy, you say “Mine!” and take the toy

- When the toddler asks where an item is, you tell the toddler the location of the item and assist/prompt to make sure they can obtain the item from the location quickly

- When a toddler asks, “What’s that?” about an item on the table, you praise the question and provide an M&M and then say, “You know what that is! What is it?”

PIVOTAL AREA: RESPONDING TO MULTIPLE CUES

Question:

An older toddler enjoys playing with wooden puzzles. Which of these examples of learning materials provide an ideal situation for teaching multiple cues?

Choose one of the following:

- flashcards with all the different combinations of colors, shapes, and sizes

- a puzzle that has one blue square, one yellow triangle, and one red circle

- a puzzle with one blue square, one red square, one blue circle, and one red circle

- any of the above

Is this statement True or False?

Teaching multiple cues is a beginning level PRT intervention target for nonverbal toddlers with autism.

Step 3 Monitoring Progress

![]()

Monitoring progress of PRT is done by selecting appropriate data to collect and using the data to make decisions. This step also involves collecting and analyzing on-going data on a toddler’s behavior during intervention for each meaningful objective.

Step 3.1 Determine whether or not PRT has been effective

Determine whether or not PRT has been effective for each meaningful

objective and for the toddler’s overall progress.

As much as possible, the difference between baseline and intervention data should be the effect of the intervention. Otherwise, parents and practitioners may be less confident about whether the intervention was actually effective.

Progress monitoring will result in either proceeding with the next goal of a successful intervention, or making a modification to a less successful intervention. If the intervention is implemented with low fidelity, that is, not as the intervention was intended, modifications or re-training are implemented.

Specific Considerations for Monitoring PRT

Much of PRT’s data collection is based on the procedures commonly used in applied behavior analysis (ABA) interventions. Select the type of data to collect based on:

- the type of target behavior,

- the intention of the intervention (e.g., to decrease or increase behavior), and

- the feasibility associated with collecting the different types of data.

Typical types of data include: frequency or event-recording (e.g., rate and percent occurrence/correct), partial and whole interval, duration, and latency recording. However, there are some additional considerations specific to PRT.

-

Data collected from language samples during play and daily routines can easily be converted into a variety of behavior data. See Planning PRT for a more in-depth look at communication samples and the types of data that can be extracted. PRT may make more frequent use of language or communication samples.

-

Data are collected within everyday environments, rather than special purpose assessment contexts.

-

Monitor whether settings and antecedents are being varied. Given that initiated, spontaneous, and generalized behaviors are key in PRT, it is important to track the varied types of prompts and instructions provided, as well as the varied settings and learning situations. These data on instructional variation assess the association between parent or practitioner instructional behaviors and child behavior and progress.

Sample Questions to Ask When Monitoring Pivotal Response Treatment

Sample Questions to Ask When Monitoring Pivotal Response Treatment

Are parents and practitioners providing enough opportunities for spontaneous or initiated child behavior, or instead are they directly initiating most of the interactions through model prompts, choices, and questions? If most of the opportunities were model prompts, this might explain lower levels of a toddler’s spontaneous use of target behaviors.

Are the acquired skills generalizing to diverse situations and are diverse situations being provided? Answering “no” suggests the need to consider teaching with more diverse stimuli, with additional people, and in multiple contexts.

Can the toddler appropriately respond to a variety of relevant antecedents and are you varying stimuli and tasks, such as cues and questions, at appropriate levels? If the toddler cannot respond appropriately, you will need to improve the implementation of PRT.

4. Vary target behaviors in trial-by-trial (opportunity-by-opportunity) data. When collecting percent correct through trial-by-trial data recording, do not provide too many of the same trial or opportunity consecutively. When collecting data on toddler performance during 10 total opportunities, those 10 opportunities are rarely provided all in a row. Avoid “drilling” target behaviors. Data collection systems can support this by providing data recording options for multiple objectives on a single form.