Reinforcement

Reinforcement is an evidence-based practice used to teach target skills and increase desired behavior. Reinforcement is a foundational practice underpinning most other evidence-based practices (e.g., prompting, pivotal response training, activity systems) for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Reinforcement describes the relationship between the toddler’s behavior/use of a skill and the consequence of that skill/behavior. The relationship between behavior/use of skill and consequence is only reinforcing if that consequence increases the likelihood that the toddler performs the skill or behavior. For example, a toddler being taught to request objects such as toys will only request if the toy is one that he desires.

Reinforcement can be positive (giving something the toddler wants) or negative (taking away something the toddler doesn’t want).

Both types of reinforcement are covered in this module:

-

Positive Reinforcement

-

Negative Reinforcement

Within this learning module, both will be presented with separate implementation steps, resources, and checklists.

Overview of Reinforcement

After reviewing this overview section, you should be able to answer the following questions about this practice:

What is Reinforcement?

Why use Reinforcement?

Where Can You Use Reinforcement?

What is the Evidence-base for Reinforcement?

What is Reinforcement?

![]()

- an evidence-based practice used to teach target skills and increase desired behavior.

- a foundational practice underpinning most other evidence-based practices (e.g., prompting, pivotal response training, activity systems) for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

- the relationship between the toddler’s behavior or use of a skill and the consequence of that skill or behavior. The relationship between behavior or use of skill and consequence is only reinforcing if that consequence increases the likelihood that the toddler performs the skill or behavior. An example would be a toddler being taught to request objects such as toys will only request if the toy is one that he desires.

There are two types of reinforcement:

Positive Reinforcement

Negative Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement (giving something the toddler wants) is the delivery of a reinforcer (primary such as food and comfort or secondary such as verbal praise, toys, or preferred activities) after the toddler does the target skill or behavior.

Negative reinforcement (taking away something the toddler doesn’t want) is the removal of an object or activity that the toddler does not like (e.g., staying at the table at dinner) when the toddler does the identified behavior or skill.

Why Use Reinforcement?

![]()

Reinforcement is an effective, foundational evidence based practice for teaching toddlers skills and increasing desirable behaviors. Effective implementation of reinforcement may also reduce challenging behaviors. As a toddler finds a positive behavior reinforcing he may decrease his use of the converse behavior.

For example, if the toddler is reinforced for saying “help” by receiving help and positive attention he is likely to decrease the screaming that brought him help in the past.

Reinforcement is a component of most other evidence-based practices. It is an essential practice because it directly connects the skill or behavior with a desirable consequence for the toddler, thus better ensuring success for the toddler. While skill acquisition may be intrinsically reinforcing to many toddlers, some toddlers who have autism spectrum disorder benefit from pairing the natural consequences of the skill or behavior with additional reinforcers. These additional reinforcers are faded over time to promote generalization and maintenances of the skill or behavior.

Reinforcement is most effective when it is individualized for the learner.

Where Can Reinforcement Be Used and By Whom?

![]()

Reinforcement can be used in any setting to support toddlers with ASD. Any parent, family member, early interventionist, child care provider, or other team member can utilize reinforcement. More than likely, these people are already reinforcing the toddler. This module describes how reinforcement should be implemented to maximize the toddler’s success by individualizing its application.

Reinforcement should be utilized throughout daily routines and activities. In particular, effective implementation of reinforcement is critical during routines and activities that are problematic for the toddler.

What is the Evidence-base for Reinforcement?

![]()

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (NPDC) initially reviewed the research literature on evidence-based, focused intervention practices in 2008. A second, more comprehensive review was completed by NPDC in 2013.

- A total of 27 EBPs are identified in the current review.

- Of the 27 practices, 10 practices that met criteria had participants in the infant and toddler age group, thus showing effectiveness of the practice with infants and toddlers with ASD.

The practices were identified as evidence-based when at least two high quality group design studies, five single case design, or a combination of one group design and three single case designed studies showed that the practice was effective. The full report is available on the NPDC on ASD website.

Reinforcement meets the evidence-based practice criteria in all age groups (birth to 21) with 43 single case design studies. For the infant and toddler age group (0 - 2), 2 single-subject design studies included toddlers with autism and demonstrated positive outcomes. In addition, 14 studies included preschool children (3 - 5). Reinforcement can be used effectively to address social, communication, behavior, joint attention, play, school readiness, motor, adaptive, and, for older learners, academic and vocational skills. A complete list of the evidence base for children aged birth to five is included in the References.

Refer to the Reinforcement Fact Sheet from the updated EBP report for further information on the literature for prompting procedures.

Knowledge Check

Question:

Why is reinforcement a particularly important evidence-based practice (EBP) to understand?

Question:

What may be the reason when a reinforcer doesn’t seem to be effecting the toddler’s behavior?

Implementation Steps

Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is at work when consequences that follow a skill or behavior result in an increase in that skill or behavior by the toddler. For example, when dumping shapes in a shape sorter results in well-loved tickles the toddler is even more likely to continue using the shape sorter. Another toddler may be reinforced to allow his shoes to be put on by mom if this activity is directly followed by outside play.

-

Reinforcement must be meaningful to the toddler. If the reinforcer chosen holds no value to the child it is very unlikely to affect her behavior. For example, while many toddlers are reinforced by social attention and physical affection, some children with autism spectrum disorders may find these aversive. For these toddlers, social praise and physical affection is unlikely to elicit increases in skill or behavior. Conducting a reinforcement sampling better ensures that reinforcers are individualized.

-

As possible, reinforcers should be natural and related to the skill or behavior. Natural reinforcers are those that would have occurred anyway if the toddler engaged in the skill/behavior. When teaching a toddler to request, the toddler’s requests should, as possible, be immediately followed by a related response to each request.

-

Multiple reinforcers are more effective than a single reinforcer (Alberto & Troutman, 2008). Pairing reinforcers helps to increase value for the toddler. A toddler, who enjoys mom’s attention, will be more likely to consistently sign for “help” by getting help from mom along with her smile and a cheerful “yay.”

-

Recognize and plan for the potential of satiation. When the reinforcer is overused it may lose value for the toddler. A toddler may not be interested in learning to put pieces in a puzzle if after every piece placed in the puzzle he gets a fuzzy ball to play with before returning to the puzzle. He may enjoy the activity and be more likely to place the pieces if the reinforcer is provided after the entire puzzle is completed. Additionally, a toddler may not find value in completing a cleanup routine if he is being reinforced by crackers just after his lunch. More information on the importance of schedules for reinforcement follows.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

The following steps describe the process by which to identify the toddler’s skill or behavior that will be targeted for the Positive Reinforcement intervention. The planning steps also describe how to identify and select reinforcers. Finally, this planning section describes schedules for reinforcement.

Step 1.1 Select and describe the target skill or behavior in observable and measurable terms

Beginning with the IFSP, the EI team discusses with the parent the strengths and challenges of the toddler in meeting a priority outcome and then describes the target skill. The IFSP outcome should be observable and measurable in order to be able to clearly describe the expected skill that the toddler will learn and how to determine when the toddler has mastered the skill.

EXAMPLE

Parents discussed with the providers that their toddler, Jonathan, doesn’t interact with them or his 5 year old sister at home.

The IFSP team initially wrote the outcome as: “Jonathan will play with his sister after day care.”

While the outcome describes the family’s hope, it is not observable and measurable and thus difficult to observe progress on over time. Different people would have different ideas of what “play” means and what it would mean for Jonathan to do it successfully. This IFSP outcome was re-written so that it was observable and measurable. To do this, the team clearly described the context (WHEN), the target skill the toddler will perform (WHAT) and how will we know Jonathan has mastered this skill (HOW).

New outcome: After daycare and before dinner, Jonathan will send at least 5 minutes interacting with his toys within 3 feet of his sister for 4 out of 5 days.

Step 1.2 Identify the activities and routines within which to teach the target behavior (or skill)

Once target behaviors are described, the EI team and parents identify everyday activities and routines within which to use positive reinforcement to increase the toddler’s behavior. Using favorite activities and routines will further increase motivation through the use of natural reinforcers for the toddler. Using family activities and routines will also support the family and other caregivers in implementing reinforcement on their own.

EXAMPLE

The team and family might decide to use reinforcement of the toddler’s requesting behaviors (signing “more” and reaching, saying “I want ___”) during highly preferred routines such as bath or snack.

For Jonathan, described in example for Step 1.1, the team might identify all the times when Jonathan and his sister have opportunities to play at the same time.

Step 1.3 Determine implementation of other evidence-based practices

Reinforcement is usually implemented in conjunction with other evidence-based practices (e.g., prompting, activity-systems, naturalistic interventions, discrete trial training).

If another evidence-based practice is being implemented review the module for that practice from the Autism Internet Modules or review the EBP Brief at the NPDC on ASD website.

Step 1.4 Collect baseline data

Once the behavior (or skill) and activities and routines are identified, the team and family collect data on that behavior within those activities or routines. This will determine how often the toddler uses the target behavior, if at all.

If an accurate baseline is not established the EI team is unlikely to develop appropriate goals and criteria by which to measure progress. Further, the EI team is unlikely to be able to make the right adjustments to the implementation of reinforcement and other evidence-based practice necessary to support the toddler and family’s success.

a) The EI team, with the family, measure the toddler’s use of the skill or behavior

Review the criteria written into the IFSP outcome to identify what type of data to collect. These types of data might include the following:

Frequency Data. Frequency data measure how often the toddler engages in the skill/behavior. Data are collected through time sampling or event sampling.

When using time sampling, data are collected after a certain amount of time has passed (e.g. every 5 minutes). For example, if collecting data on frequency of screaming behavior a parent or provider would mark if the behavior happened every 5 minutes. This technique is useful for behaviors the toddler engages in frequently such as for engagement and parallel play. For Jonathan, the team could take data every 3 minutes on whether he was engaging in play within the target distance from his sister.

Event sampling is used by marking every time that the toddler engages in the skill/behavior. This technique is used for low frequency behaviors or skills such as requesting help, playing specifically with a toy, helping put on clothes, and so on. For Jonathan, the team could mark down every time he engaged directly with his sister during play.

Data: How frequently Jack requests for more snack during snack time by signing “more”, pointing to the food, or approximating the food (“cracker”)

|

Date |

# of Requests |

Total |

|---|---|---|

|

9/17/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/18/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/19/2012 |

XXX |

3 |

|

9/20/2012 |

XXXX |

4 |

Duration data. Duration data are used to record the length of time that the toddler engages in the skill/behavior. For example, a parent or provider might collect data on how long a toddler sits at the table during dinner before demanding to be let down. A parent or provider might collect data on how long the toddler spends playing with one open-ended toy before moving on to something else. For Jonathan, the team could take data on how long he engages in parallel play with his sister.

Data Table: Length of time Caroline spends in bath before demanding to be taken out

|

Date |

Start Time |

End Time |

Total Time |

Which Bathroom Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7/4/12 |

7:18 |

7:21 |

3 |

Guest |

|

7/5/12 |

6:55 |

6:59 |

4 |

Guest |

|

7/7/12 |

7:02 |

7:07 |

5 |

Master |

|

7/8/12 |

7:22 |

7:24 |

2 |

Guest |

b) EI team members collect baseline data for a minimum of four days or until a trend is clear and stable before beginning implementation of reinforcement.

If the baseline is not stable, the team will not know whether it was the implementation of reinforcement that produced a change in the toddler’s behavior or use of a skill. A stable baseline helps the team know whether their use of reinforcement is impacting the toddler’s behavior.

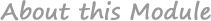

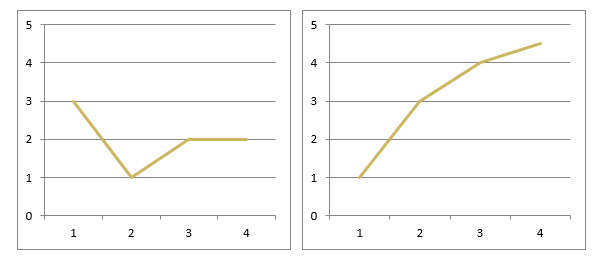

Baseline data should be graphed in order to best determine if a trend is stable such as in the following graphs. In both of the graphs below a stable trend can be identified. While the graph on the left is more erratic, it is clear that the frequency or duration of the behavior is at the level of a 2 and that the level is overall flat. The graph on the right clearly slows an increasing trend. Generally, at least 3 data points are needed to begin to identify a trend.

Step 1.5 Establish goals and criteria

Now that the team and family have identified skills/behaviors and routines, they determine the criteria that will be used to evaluate whether their use of positive reinforcement is effective. First, the team and family double check that the outcome is still appropriate given the baseline data collected. If it is not, the outcome is revised as described in the first step.

EXAMPLE

After daycare and before dinner, Jonathan will send at least 5 minutes interacting with his toys within 3 feet of his sister for 4 out of 5 days.

In Jonathan’s outcome there are multiple, clear criteria by which to measure success:

- duration of interaction with toys

- proximity to his sister

- across specific number of days

Each of these are important to track to identify when Jonathan is having trouble or making progress.

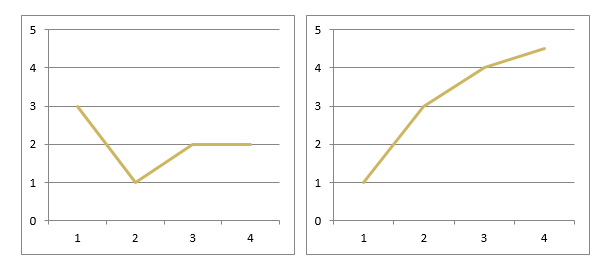

A data sheet for Jonathan’s IFSP outcome would include the following:

Step 1.6 Select positive reinforcers

The goal of reinforcement is to increase the likelihood that the toddler with ASD will use the target skill again in the future. Therefore, selected reinforcers should be highly motivating to the toddler with ASD, naturally reinforcing, and tied to the activity or routine within which the target skill or behavior will be most likely used by the toddler.

When choosing reinforcers for toddlers with ASD, the EI team identifies:

- What has motivated the toddler in the past?

- What does the toddler want that is not easily accessible by her?

For example, a toddler may continually request Goldfish crackers that are placed on a high shelf; however, the EI provider or parent only gives the toddler the Goldfish crackers a few times a day.

EI providers, parents, and/or caregivers identify a reinforcer that is appropriate for the target skill and routine or activity.

Primary reinforcers satisfy a physical need by making the toddler feel good (e.g., food, liquids, sleep).

Secondary reinforcers are objects or activities that the toddler has grown to like, but does not need biologically (e.g., tickles, stickers, ball play).

Potential Reinforcers

- Activity reinforcers include tickles with dad, going outside, time to play games on iPad, access to a bubble blower.

- Social reinforcers include verbal praise (e.g., “You did it! You put the ball in!”), “high fives”, and general body language indicating approval. Social reinforcers should be paired with other reinforcers, especially natural. Social reinforcers should also be varied and specific to the skill/behavior. A string of “good jobs” quickly become meaningless and do not tell the toddler what he did well. It is important to remember that while social reinforcers are motivating for many children, they may be less or not at all motivating for toddlers with ASD. In this case, a social reinforcer may get in the way or frustrate the toddler.

- Tangible reinforcers include objects that the toddler with ASD acquires after displaying the skill/behavior. Examples include stickers, toys, crackers, and popcorn.

- Sensory reinforcers are often motivating for toddlers with ASD. The use of these can be considered if the caregiver can control access to them, are deemed appropriate by the family, and other reinforcers have not been identified. Sensory reinforcers may include sitting in a rocking chair, getting lotion applied to hands, or playing with a favorite spinning top, to name a few.

- Natural reinforcers as those that would occur normally as a result of the child’s skill/behavior. Examples include receiving a toy after asking for it, the cow popping out of the toy after the button is pushed, or receiving a turn on the swing after requesting “swing.”

The chosen reinforcer should be as natural as possible. That is, it should be related to the activity that is going on. For example, it would be natural for a toddler with ASD to get free time or have access to a preferred activity/object after taking part in a challenging, non-preferred learning activity. Another example would be to use food as a reinforcer during food-related activities such as snack time or lunch when the target skill is requesting.

Activities Used to Identify Effective Reinforcers for a Toddler

-

Use an Interest Inventory

The family and other caregivers are likely to give valuable information about the toddler’s preferences. The Early Preschool Interest-Based Everyday Activity Checklist [ PDF file ] is one example of a checklist to use to gather information from the toddler’s family about preferred activities. This checklist provides information on activities that are reinforcing as well as the frequency of these activities within family routines and can be found at the Family, Infant, and Preschool Program Center for the Advanced Study of Excellence (CASE) website: www.fipp.org

- Observe the toddler in natural settings and identify activities, objects, foods, interactions, and so on that she chooses or seems to enjoy.

- Ask the toddler, if appropriate, what he would prefer to work for by providing the toddler with choices. For example, show the toddler two options of snack, wait for toddler to point to one he would like (if this skill is developed). Later, put the snack out of reach and instruct the toddler on how to request the snack. Reinforce with the chosen snack when toddler requests.

-

Conduct a Reinforcer Sampling

In order to decide which reinforcers, among many, are most likely to be effective conduct a reinforcement sampling. There are a number of options for completing reinforcer sampling; however, for toddlers who may have limited communication skills, the following steps are suggested:

- Gather a selection of items that may be favorable to the toddler. These items can be identified by asking caregivers and observing the toddler.

- Present the toddler with pairs of choices, being sure to match each item at least once with the other items being sampled. This is to determine relative preference. Also, vary left and right presentation throughout to minimize the possibility that the toddler is choosing one object from a particular side (e.g. side preference).

- Document the items chosen most often, least often, or that produce a notable response (e.g., the toddler throws the item after choosing it). Toddler Activities, Reinforcer Sampling, or Preference Assessment Menu (Fisher et al., 1992)

|

Date |

Reinforcer 1 |

(+) or (-) |

Reinforcer 2 |

(+) or (-) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5/01/12 |

Bubbles |

+ |

Coloring/drawing |

- |

|

|

5/01/12 |

Bubbles |

+ |

Squishy ball |

- |

|

|

5/01/12 |

Play Doh |

- |

Squishy ball |

+ |

|

|

5/01/12 |

Squishy ball |

+ |

Favorite book |

- |

|

|

5/01/12 |

Favorite book |

+ |

Play doh |

- |

|

|

5/02/12 |

Favorite book |

- |

Duplo Blocks |

+ |

|

|

5/02/12 |

Duplo Blocks |

+ |

Play doh |

- |

|

|

5/02/12 |

Duplo Block |

+ |

Coloring/drawing |

- |

|

|

5/02/12 |

Playdoh |

+ |

Coloring/drawing |

- |

|

|

5/02/12 |

Swinging |

+ |

Sitting in rocking chair |

- |

Super excited |

|

5/02/12 |

Swinging |

+ |

Trampoline |

- |

About swing! |

The following video demonstrates a provider using the reinforcement sampling technique to identify which object is most or least motivating to the child. The provider introduces the toddler to two objects and watches which object the child explores or plays with more enthusiastically or for a longer period of time.

Video: Reinforcer Sampling

Video: Reinforcer Sampling

Through the above steps, the team develops a list of reinforcers and reinforcing activities.

Step 1.7 Select a schedule of reinforcement

The schedule for reinforcement refers to the timing and frequency of the delivery of reinforcement after the toddler performs the skill/behavior. Reinforcement is delivered either continuously or intermittently.

Generally, continuous reinforcement means the reinforcement is delivered each time the toddler uses the skill/behavior until the skill/behavior is learned. Continuous reinforcement helps the toddler learn new skills quickly, but can lead to satiation. Once the toddler learns the behavior, as evidenced by them meeting a pre-established criterion, the reinforcement may be delivered intermittently. Intermittent reinforcement helps to maintain the skill/behavior over time, and should be used after the toddler learns the new skill/behavior.

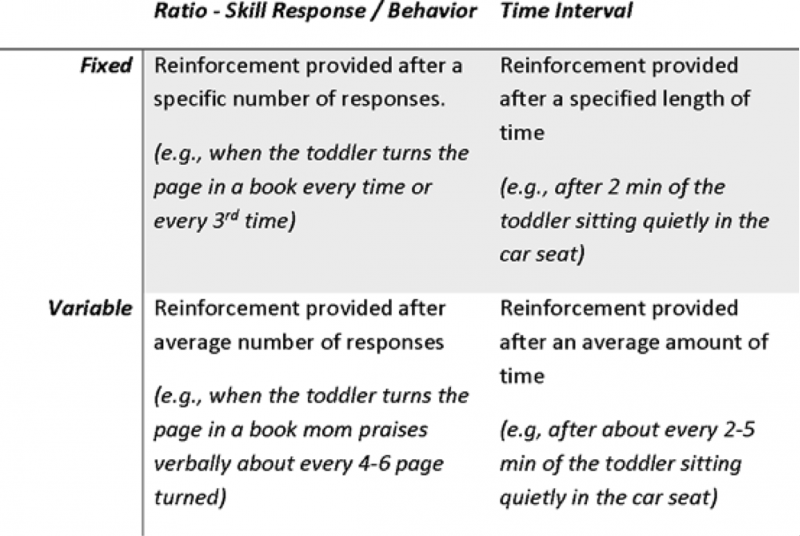

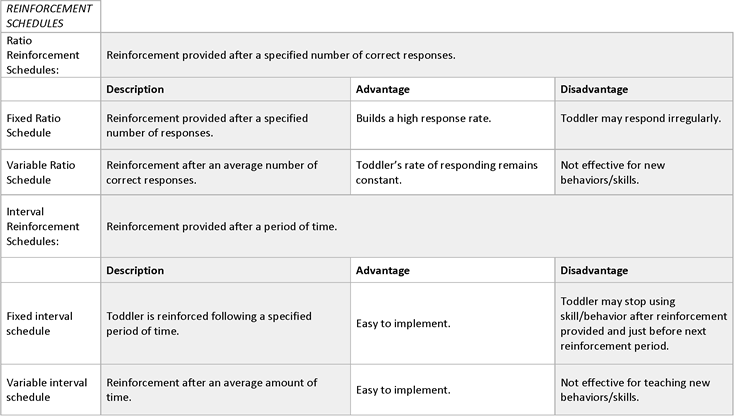

Moving from a continuous to an intermittent schedule of reinforcement is an example of reinforcement fading. Fading of reinforcement is an important step to helping the toddler learn to use the skill without the need of secondary reinforcers so that he or she can better generalize the target skill/behavior to other people, places, and activities. Intermittent reinforcement schedules can be either ratio or interval. Ratio schedules deliver reinforcement after the toddler does the skill/behavior. Interval schedule reinforcement is provided after a certain amount of time has passed.

Both ratio and interval schedules can be fixed or variable. Once the toddler learns the skill better, using these schedules ensures higher rate of success since the toddler isn’t aware of when reinforcement will be provided. Providers and families generally use a variable schedule as they provide reinforcement. At home, mom and dad have their attention pulled in various directions and will find it more challenging to provide reinforcement for every occurrence of the toddler’s skill/behavior. The following chart describes in more detail the differences between these reinforcement schedules.

The following video shows an example of fixed ratio reinforcement and variable ratio reinforcement.

Video: Fixed and Variable Ratio Reinforcement

Video: Fixed and Variable Ratio Reinforcement

In determining the best schedule for providing reinforcement to the toddler remember the following:

- General continuous reinforcement is best as the toddler learns a new skill.

- Fixed schedules are more effective for shaping behavior.

- Variable schedules are useful for helping a toddler maintain a skill.

The following table summarizes the different reinforcement schedules:

Planning Scenarios: Positive Reinforcement

The practice scenarios for using the evidence-based practice (EBP) follows a toddler example through each of the implementation steps. The practice scenarios are followed by a Knowledge Check for each step. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips

Knowledge Check

Question:

What type of reinforcement schedule is best for maintaining a skill or behavior that the toddler has already learned?

Question:

When teaching a new skill, which reinforcement schedule is most effective to start with?

Consider the following question:

What are at least three types of reinforcers?

Step 2 Implementing the EBP

![]()

The following steps describe the process of using Positive Reinforcement through implementation of continuous reinforcement and preventing satiation.

Step 2.1 Implement continuous reinforcement

When first learning a behavior (or skill), a toddler needs to know when she is doing the behavior and doing it correctly.

Reinforcement needs to occur, as possible, after every occurrence of the behavior.

- Provide reinforcement immediately after the toddler performs the behavior (or skill). Ensuring immediacy helps the toddler to make the connection between their performance of the behavior and getting the reinforcer.

- As the reinforcer is provided name the behavior. Example, after the toddler requests juice by pointing and saying “ju”, give the toddler the juice (reinforcer) while saying “You want juice!”

- Only provide the reinforcer when the toddler is performing the behavior. For example, a dad uses goldfish crackers plus verbal praise to reinforce his son’s asking for “fish” during snack, but then leaves the goldfish out for the rest day for his son to access whenever he wants. His son may be less likely to use his new skill of requesting verbally or he may lose interest in the reinforcer all together.

- Provide small amounts of the reinforcer to maintain the toddler’s interest in it. Again, if dad gives his son 2 goldfish over 20 goldfish crackers his son is less likely to lose interest and will have many more opportunities to learn to request.

- When the use of primary reinforcers cannot be avoided, pair primary reinforcers with secondary reinforcers (e.g., food, drink paired with an activity, or tangible/sensory reinforcers). When the toddler requests “juice” say “Juice! You want juice!” to help the toddler associate the specific behavior to reinforcer AND to support the toddler in understanding the value of secondary reinforcers.

- Pair reinforcers with social reinforcement. Ensure that social reinforcement is specific to the behavior and is varied. Observe to make sure that the social praise is not aversive to the toddler (e.g., too loud, too big, too intense). Pairing other reinforcers with social reinforcers helps toddlers understand the value of social praise. Toddlers with ASD are less likely to appreciate the value of social praise as much as their typically developing peers. As the toddler becomes more motivated by the social reinforcer, begin to fade the reinforcer (activity, edible, sensory, tangible).

Step 2.2 Prevent satiation

Reinforcement works because the toddler is motivated to do the skill or behavior in order to get something he desires. Thus it is important to plan for how to keep the desired item, food, activity, or thing motivating to the toddler and to prevent satiation.

Remember that as with anyone, what is motivating today may not be as motivating tomorrow.

![]()

Tips for Preventing Satiation |

|

|---|---|

|

To Avoid Satiation: |

Examples: |

|

After conducing reinforcer sampling, observation, and/or interest inventory keep on hand a number of the reinforcers identified. |

|

If the toddler very much enjoys tickles and silly faces, alternate tickles or silly faces when providing reinforcement for a skill/behavior. If the same toddler also enjoys pretzels, consider keeping pretzels as reinforcer for snack time and tickles are reinforcers for playtime. |

|

Several short sessions helps to ensure that the toddler won’t tire of the reinforcer before he has enough opportunities to practice the skill/behavior. |

|

Edibles (a primary reinforcer) should be used only when other reinforcers have not been identified or if the edible is a natural reinforcer (e.g., the toddler requests juice then juice is provided). If used, various types should be used and they should be paired with other types of reinforcement. |

|

Since toddlers with ASD are less likely than their typically developing peers to value secondary reinforcers, pair these with more valued reinforcers from the beginning. As the toddler becomes more motivated by secondary reinforcer, fade the primary reinforcer. |

|

If the toddler stops using the skill or behavior after mastering it or shows disinterest in reinforcer, change it. An inventory or reinforcer sampling may need to be repeated if no other reinforcers are immediately apparent. |

The following video clip shows the ways in which a reinforcer is provided in small segments throughout a task to maintain interest on the task and avoid satiation.

Video: Using Reinforcement to Avoid Satiation

Video: Using Reinforcement to Avoid Satiation

Practice Scenarios: Implementing Positive Reinforcement

The practice scenarios provide examples of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) and follow a toddler situation through each of the implementation steps. A knowledge check follows the practice scenarios.. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips

Knowledge Check

Question:

An almost three year old has learned to take turns with his brother during short games. All of a sudden, he does not want to take turns anymore, which distresses his brother.

What issues related to reinforcement might be at work?

Question:

When implementing reinforcement providing large amounts of the reinforcer should be avoided. Why?

Question:

When implementing reinforcement it may be necessary to pair reinforcers (such as social reinforcers with primary reinforcers). Why?

Step 3 Monitoring Progress

![]()

The following steps describe how the implementation of Positive Reinforcement is monitored and how to adjust the implementation plan based on the data.

Step 3.1 Use progress monitoring data to determine the toddler’s mastery of the skill or behavior

Data must be taken and monitored in order to determine if the planned intervention is working and when reinforcement can be gradually faded. Fading reinforcement is very important to promote generalization and maintenance of the toddler’s use of the skill or behavior.

Data should be taken on the data sheets developed for the baseline data, unless through the course of intervention it is determined by the team and family that other information will be most useful. By using the same data collection sheets, the team and family can track the toddler’s performance before reinforcement was implemented and after it was implemented. Therefore, the team and family will be better able to see if the toddler shows an increase in using the target skill/behavior after they implemented reinforcement. If not, changes will need to be made to the intervention plan such as using different reinforcers, reinforcing more consistently, saving reinforcers for teaching times only, and so on.

Data on how frequently Jack requests for snack during snack time by pointing to the food or approximating the food “cracker.”

|

Date |

# of Requests |

Total |

|---|---|---|

|

9/18/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/18/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/19/2012 |

XXX |

3 |

|

9/20/2012 |

XXXX |

4 |

|

9/22/2012 |

XXXX |

4 |

|

9/22/2012 |

XXXXXXX |

7 |

|

9/23/2012 |

XXXXXX |

6 |

|

9/24/2012 |

XXXXXXX |

7 |

|

9/25/2012 |

XXXXXXXX |

8 |

Data on the length of time Caroline spends in bath before demanding to be taken out.

|

Date |

Start Time |

End Time |

Total Time |

Bathroom Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7/4/12 |

7:18 |

7:21 |

3 |

Guest |

|

7/5/12 |

6:55 |

6:59 |

4 |

Guest |

|

7/7/12 |

7:02 |

7:07 |

5 |

Master |

|

7/8/12 |

7:22 |

7:24 |

2 |

Guest |

|

7/10/12 |

6:45 |

6:47 |

2 |

Guest |

|

7/11/12 |

7:00 |

7:07 |

7 |

Guest |

|

7/12/12 |

7:05 |

7:14 |

9 |

Master |

|

7/14/12 |

7:05 |

7:17 |

12 |

Master |

Step 3.2 Move from continuous to intermittent reinforcement

As the toddler moves towards meeting the outcome criterion, the team and family begin to fade or move from a continuous schedule of reinforcement to an intermittent schedule of reinforcement. Return to Step 1.6 for a review of intermittent schedules of reinforcement.

Fading reinforcement from a continuous schedule (every time the toddler performs the skill or behavior) to intermittent schedule helps the toddler learn to use the skill or behavior more frequently, to maintain the behavior over longer periods of time, and reinforces the behavior with more available reinforcers (e.g., praise, natural consequences).

Data are taken throughout this process to make sure that fading in reinforcement is not causing a decrease in the use of the skill or behavior.

EXAMPLE

After daycare and before dinner, Jonathan will send at least 5 minutes interacting with his toys within 3 feet of his sister for 4 out of 5 days.

Reinforcement for acquisition: While learning the skill, the EI provider and mom reinforce Jonathan with praise and access to a preferred toy every 30 seconds that he plays within 3 feet of his sister.

Reinforcement for maintenance: Once Jonathan is consistently playing with his preferred toys within 3 feet of his sister, the EI provider and mom provide less preferred toys until he again reaches criterion. After that criterion is reached social praise is provided every 2 minutes.

Step 3.3 Use data to adjust reinforcement strategies if the skill or behavior is not increasing

Data collection and review provides visual evidence of the effectiveness of the reinforcement strategy being used. If the skill or behavior is not increasing, the EI team and family must try to identify the reason why.

Questions that can help identify the reason why the target skill or behavior is not increasing:

- Is the skill or behavior well defined? Is it measurable and observable?

- Are the reinforcers motivating to the toddler?

- Are there too few different reinforcers? Are there too many?

- Is everyone using the reinforcers consistently?

- Are the reinforcers provided at a level necessary to maintain behavior? Should they be provided continuously?

Practice Scenarios: Monitoring Positive Reinforcement

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) that follow a toddler case through each of the implementation steps, following the Knowledge Check. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips.

Knowledge Check

Fill in the blank:

Collecting implementation data on the same data sheets as baseline data is helpful in order to __________________.

Question:

What are the benefits to moving from a continuous to an intermittent reinforcement schedule?

Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is the removal of an unpleasant event when the toddler engages in the behavior or skill. Like positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement leads to an increase in the toddler’s use of the skill or behavior.

-

Negative reinforcement is NOT punishment. Punishment is meant to decrease behavior while negative reinforcement is meant to increase behavior by taking away the aversive or unpleasant event.

-

Negative reinforcement is generally used to teach a target skill/behavior to take the place of an interfering behavior. For example, when the toddler says “help” instead of screaming he is given the item he wanted which was being held by his mom.

-

Negative reinforcement is generally used when using positive reinforcement has been ineffective in teaching the toddler a replacement skill or behavior.

-

Since negative reinforcement is generally used to teach a replacement skill, negative reinforcement may lead to an increase in the challenging behavior. This may happen if the negative reinforcer chosen is not of value for the toddler or if the toddler does not make the connection between the aversive being removed due to his use of the replacement behavior or skill.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

The following planning steps describe the process by which to identify the toddler’s skill or behavior that will be targeted for the Negative Reinforcement intervention. The steps also describe how to identify and select potential negative reinforcers.

Step 1.1 Select and describe the target skill or behavior in observable and measurable terms

Beginning with the IFSP, the EI team discusses with the parent the toddler's strengths and challenges in order to develop a priority outcome and then describe a target skill. The IFSP outcome should be observable and measurable in order to be able to clearly describe the expected skill that the toddler will learn and how to determine when the toddler has mastered the skill.

EXAMPLE

Parents discussed with the providers that their toddler, Aiden, preferred to graze rather than sit for meals. The team assessed whether this behavior was very different from the grazing behavior of most toddlers. Based on their observations, the team agreed that sitting for mealtime was something that Aiden disliked. The team helped the family to craft an observable and measurable outcome, which clearly described the context (WHEN), the target skill the toddler will perform (WHAT) and how will we know Aiden has mastered this skill (HOW).

Outcome: During dinner, Aiden will sit in his seat for at least 5minutes and finish at least 5 bites of food before leaving the table for 4/5 consecutive weekday dinners.

Creating an observable, measurable outcome ensures that the family and team can keep information on the behavior that tells them if the toddler is clearly progressing or if a change in the intervention needs to occur. The team considers how progress on sitting and progress on eating would need to be assessed separately.

They decide to look at both:

- During dinner, Aiden will sit in his seat eating or playing for at least 5 minutes before leaving the table for 4/5 consecutive weekday dinners.

- During dinner, Aiden will finish at least 5 bites of food (i.e. teaspoon size) before leaving the table for 4/5 consecutive weekday dinners.

Step 1.2 Identify the activities and routines within which to teach the target behavior (or skill)

Once target behaviors are described, the EI team and parents identify everyday activities and routines within which to use negative reinforcement to increase the toddler’s behavior. Negative reinforcement is effective when used in routines and activities that are mildy aversive to the toddler.

It is important to note, that mildly aversive activities, events, or items occur naturally in a young child’s environment and do not cause harm to toddlers with ASD.

Toddlers may be bothered by taking a bath, sitting for dinner, having the light off in the room at bedtime, and so on.

Step 1.3 Determine implementation of other evidence-based practices

Negative reinforcement is usually implemented in conjunction with other evidence-based practices (e.g., prompting, activity systems, naturalistic interventions, and discrete trial training). If another evidence-based practice is being implemented review the module for that practice.

Step 1.4 Collect baseline data

Once the skill or behavior and activities or routines are identified, the team and family collect data on that skill or behavior within those activities or routines to determine how often the toddler uses the target skill or behavior if at all. Conducting a baseline clearly illustrates the toddler’s current performance level. If an accurate baseline is not established the EI team is unlikely to develop appropriate goals and criteria by which to measure progress. And further, the EI team is unlikely to be able to make the right adjustments to their and the family’s implementation of reinforcement and other evidence-based practice necessary to support the toddler and family’s success.

a) The EI team, with the family, measure the toddler’s use of the skill or

behavior by collecting the following data:

Frequency data

Frequency data measures how often the toddler engages in the skill/behavior. Data are collected through time sampling or event sampling.

Sampling: When using time sampling, data are collected after a certain amount of time has passed (e.g. every 5 minutes). For example, if collecting data on frequency of screaming behavior a parent or provider would mark if the behavior happened every 5 minutes. This technique is useful for behaviors the toddler engages in frequently such as for engagement and parallel play.

Event sampling: Event sampling is used by marking every time that the toddler engages in the behavior. This technique is used for low frequency behaviors or skills such as requesting help, playing specifically with a toy, helping put on clothes, and so on.

For Aiden, the team could take frequency data on the number of bites that he eats during a sitting.

Data: How frequently Jack requests for more snack during snack time by signing “more”, pointing to the food, or approximating the food (“cracker”).

The event sampling data shows that his use of requests increased across the four days that data was collected:

|

Date |

# of Requests |

Total |

|---|---|---|

|

9/18/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/18/2012 |

X |

1 |

|

9/19/2012 |

XXX |

3 |

|

9/20/2012 |

XXXX |

4 |

Duration data

Duration data are used to record the length of time that the toddler engages in the skill/behavior. For example, a parent or provider might collect data on how long a toddler sits at the table during dinner before demanding to be let down. A parent or provider might collect data on how long the toddler spends playing with one open-ended toy before moving on to something else.

Data: The length of time that Aiden sits at a table eating or playing

|

Date |

Start Time |

End Time |

Total Time |

Playing or Eating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

5/9 |

5:55 |

5:57 |

3 |

Playing with blocks |

|

5/10 |

5:55 |

5:59 |

4 |

Eating/playing with blocks |

|

5/11 |

5:43 |

5:45 |

2 |

Eating/playing with cars |

|

5/12 |

5:40 |

5:43 |

3 |

Playing with blocks |

Data: The length of time that a toddler spends in each bathroom's tub before demanding to be taken out.

Although the time in bath increased it’s not clear whether that is due to time or whether Caroline prefers the master bathroom.

|

Date |

Start Time |

End Time |

Total Time |

Bathroom Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

7/4/12 |

7:18 |

7:21 |

3 |

Guest |

|

7/5/12 |

6:55 |

6:59 |

4 |

Guest |

|

7/7/12 |

7:02 |

7:07 |

5 |

Master |

|

7/8/12 |

7:22 |

7:24 |

6 |

Master |

b) EI team members collect baseline data for a minimum of four days or until a

trend is clear and stable before beginning implementation of reinforcement

A stable baseline helps the team know whether their use of reinforcement is impacting the toddler’s behavior. If the baseline is not stable, the team will not know whether it was their and the family’s implementation of negative reinforcement that produced a change in the toddler’s behavior or use of a skill.

Baseline data should be graphed in order to best determine if a trend is stable such as in the following graphs. The graph below illustrates the number of times a day a toddler urinated in a potty across 4 days. In both of the graphs below a stable trend can be identified. While the graph on the left is more erratic, it is clear that the frequency or duration of the behavior is at the level of a 2 and that the level is overall flat. The graph on the right clearly slows an increasing trend. Generally, at least 3 data points are needed to begin to identify a trend.

Step 1.5 Establish goals and criteria

Now that the team and family have identified skills or behaviors and routines, they determine the criteria that will be used to evaluate whether their use of negative reinforcement is effective.

First, the team and family double check that the outcome is still appropriate given the baseline data collected. If it is not, the outcome is revised as described in the first step.

EXAMPLE

During the span of dinner, Aiden will sit in his seat for at least 5 minutes and finish at least 5 bites of food before leaving the table for 4 out of 5 consecutive weekday dinners.

In Aiden’s outcome there are multiple, clear criteria by which to measure success:

- duration of sitting at the table

- number of bites taken

- across specific number of days

Step 1.6 Select negative reinforcers

The goal of both positive and negative reinforcement is to increase the likelihood that the toddler with ASD will use the target skill again in the future.

As mentioned earlier, negative reinforcement is effective when used in routines and activities that are mildy aversive to the toddler. When using negative reinforcement, identification of mildly aversive, non-preferred activities and tangible items is critical to ensure that the toddler is motivated to use the target behavior to avoid or get rid of the aversive activity or item. As with positive reinforcement, team members and families begin with an assessment of preferred and non-preferred items or activities.

Team members conduct a negative reinforcement assessment that identifies preferred or nonpreferred activities, events, and items that produce positive and negative reactions in the toddler with ASD.

The EI team and family come together to:

- Make a list of preferred and nonpreferred activities, events, and items

The EI team give examples to the family to help them begin to consider activities and events if needed. These may include washing hands, turning on water faucet, sitting for extended periods of time, waiting for materials to be available, certain food, certain toys, certain textures and so on.

- Observe the toddler

During the observation they direct the toddler to engage in various activities and with various toys and other items. They look for the toddler’s response (e.g., positive, negative, disinterested). If the toddler makes evasive movement or negative vocalizations (e.g., turning away, physically resisting, crying, screaming, dropping to the floor, yelling), or engages in interfering behaviors (e.g., self-injury, aggression, disruption, trying to leave) they allow the toddler to leave the activity or offer another object. Observe if the behavior decreases when the aversive event, activity, or object is removed.

The following table can be used to document the toddler’s reactions to presented activities, events, and items and the toddler’s reactions when aversive activities, events, and items are removed. Sitting in seat is clearly an aversive for Aiden. From the observation, the team also has a list of potential reinforcers to support intervention – Elmo, water play, etc.

|

Time / Activity / Place |

Reinforcers |

Aversive |

Toddler’s Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

|

11 am before lunch exploring |

|

|

|

|

Lunch in the dining room |

|

NOT tomatoes |

|

Step 1.7 Identify a reinforcer that is appropriate for the target skill and routine or activity

The team considers the list of reinforcers and mild aversives identified through interviews with family members and observations of the toddler. They identify those that are appropriate for the target skill within the identified routines or activities.

Examples of negative reinforcers used during common toddler routines or activities:

|

Target Behavior or Skill within Activity or Routine |

Aversive Aspect |

Target Behavior |

Reinforcing Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|

|

During dinner, Aiden will finish at least 5 bites of food (i.e. teaspoon size) before leaving the table for 4 out of 5 consecutive weekday dinners. |

Sitting at the table |

Eats 5+ bites |

Mom or dad removes the expectation that Aiden sits at the table by allowing Aiden to leave |

|

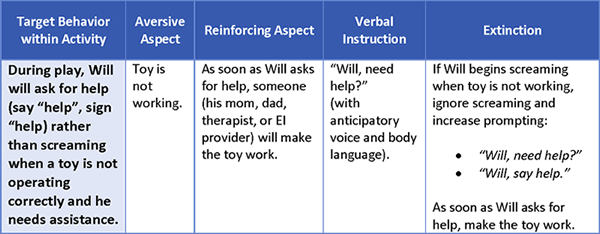

During play, William will ask for help (say “help”, sign “help) rather than screaming when a toy is not operating correctly and he needs assistance. |

Toy not working |

Ask for help |

Make the toy work |

|

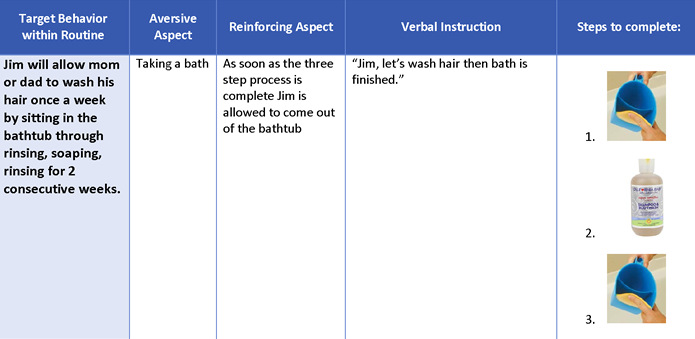

Jim will allow Mom or Dad to wash his hair once a week by sitting in the bathtub through rinsing, soaping, rinsing. |

Taking a bath |

Allowing 3 step bath process |

Expectation to stay in bathtub ends |

Step 1.8 Select a method for instruction

When using negative reinforcement it is important to plan for the method of instruction. This is so the toddler is clear what behavior or skill is expected for him to escape the aversive situation. Instructions should be determined based on:

- the individual toddler’s preferences,

- developmental level,

- the behavior or skill, and

- activity or routine.

Instructions are most often verbal, visual, or a combination of the two.

Please review the Prompting Module for more information on prompts which work well for some toddlers and how to implement these systematically.

a) Verbal instructions should be brief, clear, and consistent with the toddler’s

ability to understand receptively.

Early intervention providers and family members should determine what verbal instructions will be used so that they are consistent in the delivery of these instructions.

|

Target Behavior or Skill within the Activity or Routine |

Aversive Aspect |

Reinforcing Aspect |

Verbal Instruction |

|---|---|---|---|

|

During dinner, Aiden will finish at least 5 bites of food (i.e. teaspoon size) before leaving the table for 4/5 consecutive weekday dinners. |

Having to eat |

As soon as Aiden eats at least 5 bites he can leave the table |

Aiden, first eat, then leave table. |

|

During play, William will ask for help (say “help”, sign “help) rather than screaming when a toy is not operating correctly and he needs assistance. |

Toy not working |

As soon as Will asks for help someone (e.g., mom, dad, therapist, provider) will make the toy work |

Will, need help? (with anticipatory voice and body language) |

|

Jim will allow mom or dad to wash his hair once a week by sitting in the bathtub through rinsing, soaping, rinsing. |

Taking a bath |

As soon as the three step process is complete Jim is allowed to come out of the bathtub |

Jim, let’s wash hair then bath is finished. |

b) When incorporating visual supports it is important to ensure that they are

consistent with the developmental level of the toddler.

Many toddlers with autism react well to visual supports. Some toddlers may not be able to make the necessary connection between an abstract black/white drawing of a toy and a toy itself, but they may make the connection given a photograph of the toy. Other toddlers may need to see the actual object to understand the instruction. Early intervention providers should talk with the toddler’s family, observe the toddler, and take data on the toddler’s reaction to various visuals to determine the type and format of visuals that are most likely to be understood by the child.

Please refer to the Visual Supports Module for more information.

Examples of visual instruction:

|

Target Skill or Behavior within Activity/Routine |

Aversive Aspect |

Reinforcing Aspect |

Verbal Instruction |

Visual Instruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

During dinner, Aiden will finish at least 5 bites of food (i.e. teaspoon size) before leaving the table for 4 - 5 consecutive weekday dinners.

|

Having to eat |

As soon as Aiden eats at least 5 bites he can leave the table |

Aiden, first eat, then leave table |

|

|

During play, Will will ask for help (say “help”, sign “help) rather than screaming when a toy is not operating correctly and he needs assistance for 4 - 5 opportunities across 2 days. |

Toy not working |

As soon as Will asks for help someone (e.g., mom or therapist, provider) will make the toy work |

Will, need help? (with anticipatory voice and body language) |

Help Mom! |

|

Jim will allow mom or dad to wash his hair once a week by sitting in the bathtub through rinsing, soaping, rinsing for 2 consecutive weeks. |

Taking a bath |

As soon as the three step process is complete Jim is allowed to come out of the bathtub |

Jim, let’s wash hair then bath is finished. |

|

|

Arianna will sit on her bottom or knees in the pew at church on Sunday for at least 5 minutes before leaving for the church garden 2 - 3 consecutive Sundays. |

Sitting at church |

As soon as she finishes sitting for 5 minutes Arianna can leave |

___ more minutes sitting Arianna then garden |

|

c) A combination of verbal (or other prompt) and visual instruction can be

used.

The EI team and family members should determine that the toddler responds well to multiple forms of instruction and is not likely to be overwhelmed by these. The team should clearly outline how these instructions will be given so that all members are delivering them consistently. The toddler will learn best when expectations appear to be the same across EI team members and family members.

Planning Scenarios: Negative Reinforcement

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) that follow a toddler case through each of the implementation steps, following the Knowledge Check. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips.

Knowledge Check

Is this statement True or False?

Toddlers are developmentally ready for visual supports to be used in conjunction with negative reinforcement by 24 months.

Select an answer:

As mentioned earlier, negative reinforcement is effective when used in routines and activities that are __________________ to the toddler.

- highly motivating

- mildly aversive

- new

Question:

When measuring how often the toddler engages in a skill or behavior, what type of data should be collected?

Question:

An EI provider would like to collect data on what happens during car rides, since mom is concerned about the amount of screaming and frustration her son exhibits during car rides.

-

What type of data should she collect?

-

Why this type?

Step 2 Implementing Negative Reinforcement

![]()

The following steps describe the process of using Negative Reinforcement through implementation of continuous reinforcement and preventing satiation.

Step 2.1 Cue the toddler to use the skill or behavior

Use the methods of instruction selected in Step 1.7 to cue the toddler to use the skill or behavior.

Do not remove the negative reinforcer (the mildly aversive situation) until the toddler uses the skill or behavior.

Example of an Implementation Plan for Negative Reinforcement

In the following implementation plan for negative reinforcement with a toddler, the parent and the EI provider would cue the child, Jim, to take a bath and cue him through the steps until they are complete. Only when complete will Jim be able to leave the tub.

Step 2.2 Respond to the toddler based on the toddler's use of the skill or behavior

Respond using one of the following choices depending on the toddler's use of the skill or behavior:

a. If the toddler uses the skill/behavior, remove the negative reinforcer immediately.

b. If the toddler does not engage in the skill/behavior repeat your planned instruction.

If the toddler continues to not respond, reconsider your planned instruction. Instruction should include a control prompt. A control prompt is the most intrusive prompt, which will guarantee that the toddler engages in the skill/behavior If the toddler doesn’t engage in the skill or behavior, the chosen control prompt needs to be changed to one that will ensure the toddler’s response.

Video: Using Negative Reinforcement

Video: Using Negative Reinforcement

In this video, the provider uses the mild aversive of holding her hand over the popup toy as a negative reinforcer. As soon as the child asks for her to move her hand by saying “please,” the aversive is removed.

c. Negative reinforcement is often used to teach the toddler skills or behaviors to replace interfering behavior.

Extinction is an evidence-based practice often used during the implementation of negative reinforcement when the toddler engages in interfering behavior.

When using extinction, ignore the interfering behavior while prompting the toddler to use the target skill/behavior. Extinction should not be used if the challenging behavior is dangerous to the toddler or others.

Practice Scenarios: Implementing Negative Reinforcement

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) that follow a toddler case through each of the implementation steps, following the Knowledge Check. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips.

Knowledge Check

Select an answer:

When implementing negative reinforcement, you should ensure which of the following?

- You remove the aversive immediately upon when the toddler uses the target behavior.

- The aversive is actually aversive and that you can remove its presence quickly.

- Your corresponding prompting hierarchy includes a controlling prompt if the toddler needs prompting to get to the use of the target behavior.

- All of the above

Is this statement True or False?

Extinction is often used when the toddler engages in the challenging behavior during implementation of reinforcement.

Fill in the blank:

When should extinction not be used?

Step 3 Monitoring Progress

The following steps describe how the implementation of Negative Reinforcement is monitored and how to adjust the implementation plan based on the data.

3.1 Use progress monitoring data to determine the toddler’s mastery of the skill or behavior

Data must be taken and monitored in order to determine if the planned intervention is working.

Data should be taken on the data sheets developed for the baseline data, unless through the course of intervention it is determined by the team and family that other information will be most useful. By using the same data collection sheets, the team and family can track the toddler’s performance before negative reinforcement was implemented and after it was implemented. Therefore, the team and family will be more able to see if progress increased after they used negative reinforcement. If not, changes will need to be made to the intervention plan.

EXAMPLE

During structured playtime, Peter will request a break from the activity by giving “all done” card, instead of screaming, for 4 of 5 opportunities during 30 minutes of play across 3 days.

|

Date |

# break cards |

# of screams |

Before, during, or after implementation of negative reinforcement |

|---|---|---|---|

|

9/18 |

|

XXXXXXXX |

before |

|

9/18 |

|

XXXXXXX |

before |

|

9/19 |

|

XXXXXXXXXXX |

before |

|

9/20 |

|

XXXXXXXX |

before |

|

9/22 |

XX |

XXXXXXX |

during |

|

9/22 |

XXXX |

XXX |

during |

|

9/23 |

XXXXXX |

XX |

during |

|

9/24 |

XXXXXXX |

|

during |

|

9/25 |

XXXXXXXX |

X |

during |

As is clear from the data, as the visual and negative reinforcement intervention was implemented, Peter replaced the screaming behavior with asking for a break as instructed.

3.2 Adjust negative reinforcement strategies if the target skill or behavior is not increasing

Data collection and review provides visual evidence of the effectiveness of the negative reinforcement strategy being used. If the skill/behavior is not increasing, the EI team and family must try to identify the reason why.

The following questions can help identify the issue if the target behavior is not increasing:

The following questions can help identify the issue if the target behavior is not increasing:

- Is the skill or behavior well defined? Is it measurable and observable?

- Is the negative reinforcer actually aversive to the toddler?

- Is the toddler able to access the removal of the negative reinforcer without using the target skill or behavior?

- Is everyone using the negative reinforcers consistently?

- Is the negative reinforcer being removed immediately as soon as the toddler uses the target skill or behavior?

Practice Scenarios: Monitoring Negative Reinforcement

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the evidence-based practice (EBP) that follow a toddler case through each of the implementation steps, following the Knowledge Check. We recommend that you select and follow the same setting (home or center-based) throughout the module steps.

If you have trouble viewing, review the Troubleshooting Tips

Sample Data Sheet: Monitoring Progress of Negative Reinforcement (Caitlyn's Data)

Sample Data Sheet: Monitoring Progress of Negative Reinforcement (Caitlyn's Data)

Sample Data Sheet: Monitoring Progress of Negative Reinforcement (Desmond's Data)

Sample Data Sheet: Monitoring Progress of Negative Reinforcement (Desmond's Data)

Knowledge Check

Question:

How is collecting implementation data on the same data sheets as baseline data helpful?

Question:

If the toddler is not progressing in their use of the target skill, what questions might the team ask about their use of negative reinforcement.

Module Resources

View a description for each of the module resources

Implementation Checklist for Positive Reinforcement

Implementation Checklist for Positive Reinforcement

Implementation Checklist for Negative Reinforcement

Implementation Checklist for Negative Reinforcement

Parent & Practitioner Guide to Reinforcement (Positive and Negative)

Parent & Practitioner Guide to Reinforcement (Positive and Negative)

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

References

Research Articles for the Birth to 3 Year Age Group

Esch, B. E., Carr, J. E., & Grow, L. L. (2009). Evaluation of an enhanced stimulus‐stimulus pairing procedure to increase early vocalizations of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(2), 225-241. Doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009. 42-225.

Young, J. M., Krantz, P. J., McClannahan, L. E., & Poulson, C. L. (1994). Generalized imitation and response‐class formation in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(4), 685-697. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994. 27-685.

Research Articles for the 3 to 5 Year Age Group

Groskreutz, M. P., Groskreutz, N. C., & Higbee, T. S. (2011). Response competition and stimulus preference in the treatment of automatically reinforced behavior: A comparison. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(1), 211-215. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-211

Hagopian, L. P., Fisher, W. W., & Legacy, S. M. (1994). Schedule effects of noncontingent reinforcement on attention‐maintained destructive behavior in identical quadruplets. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 317-325. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317

Higbee, T. S., Carr, J. E., & Patel, M. R. (2002). The effects of interpolated reinforcement on resistance to extinction in children diagnosed with autism: A preliminary investigation. Research in developmental disabilities, 23(1), 61-78. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00092-0

Koegel, L. K., Camarata, S. M., Valdez-Menchaca, M., & Koegel, R. L. (1997). Setting generalization of question-asking by children with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 102(4), 346-357. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1998)102<0346:SGOQBC>2.0.CO;2

Kohler, F. W., Strain, P. S., Maretsky, S., & DeCesare, L. (1990). Promoting positive and supportive interactions between preschoolers: An analysis of group-oriented contingencies. Journal of Early Intervention, 14(4), 327-341. doi: 10.1177/105381519001400404

LeBlanc, L. A., Carr, J. E., Crossett, S. E., Bennett, C. M., & Detweiler, D. D. (2005). Intensive outpatient behavioral treatment of primary urinary incontinence of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(2), 98-105. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200020601

Levin, L., & Carr, E. G. (2001). Food selectivity and problem behavior in children with developmental disabilities analysis and intervention. Behavior Modification, 25(3), 443-470. doi: 10.1177/0145445501253004

Normand, M. P., & Beaulieu, L. (2011). Further evaluation of response‐independent delivery of preferred stimuli and child compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(3), 665-669. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-665

Nuzzolo-Gomez, R., Leonard, M. A., Ortiz, E., Rivera, C. M., & Greer, R. D. (2002). Teaching children with autism to prefer books or toys over stereotypy or passivity. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4(2), 80-87. doi: 10.1177/109830070200400203

Reichle, J., Johnson, L., Monn, E., & Harris, M. (2010). Task engagement and escape maintained challenging behavior: differential effects of general and explicit cues when implementing a signaled delay in the delivery of reinforcement. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(6), 709-720. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0946-6

Sidener, T. M., Shabani, D. B., Carr, J. E., & Roland, J. P. (2006). An evaluation of strategies to maintain mands at practical levels. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27(6), 632-644. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2005.08.002

Tarbox, R. S., Ghezzi, P. M., & Wilson, G. (2006). The effects of token reinforcement on attending in a young child with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 21(3), 155-164. doi: 10.1002/bin.213

Tsiouri, I., & Greer, R. D. (2007). The role of different social reinforcement contingencies in inducing echoic tacts through motor imitation responding in children with severe language delays. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 4(4), 629-647

Volkert, V. M., Vaz, P., Piazza, C. C., Frese, J., & Barnett, L. (2011). Using a flipped spoon to decrease packing in children with feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(3), 617-621. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-617

All Other Ages Research

Other Resources

Autism Internet Modules. http://www.autisminternetmodules.org

Glossary

Module Evaluation Survey

Please take a moment to provide valuable feedback for this learning module. Use the "Take the Module Evaluation Survey" link below to begin the evaulation.