Prompting

Prompts are generally given by an adult before or as a toddler attempts to use a skill. With prompting procedures, parents, family members, early interventionists, child care providers, or other team member can use different types of prompts systematically to help toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) acquire target skills.

A variety of prompting procedures support the learning and development of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Two types of prompting procedures are covered in this module:

-

Least-to-Most Prompting

-

Graduated Guidance Prompting

Within this learning module, both prompting procedures will be presented with separate implementation steps, resources, and checklists.

Which Prompting Procedure to Use?

Which Prompting Procedure to Use?

Overview

![]()

After reviewing this overview section, you should be able to answer the following questions about this practice:

What is Prompting?

Why Use Prompting?

Where Can Prompting Be Used and by Whom?

What is the Evidenc-base for Prompting?

What is Prompting?

A prompt is a specific form of assistance given by an adult before or as the toddler attempts to use a skill. With these procedures, parents, family members, early interventionists, child care providers, or other team members can use different types of prompts systematically to help toddlers with ASD acquire target skills (Neitzel, J. & Wolery, M, 2009).

Prompts are generally given by an adult before or as a toddler attempts to use a skill. With prompting procedures, parents, family members, early interventionists, child care providers, or other team member can use different types of prompts systematically to help toddlers with ASD acquire target skills (Neitzel, J. & Wolery, M, 2009).

Prompting procedures include any help given to learners that assist them in using a specific skill. Verbal, gestural, or physical assistance is given to learners to assist them in acquiring or engaging in a targeted behavior or skill. Prompting procedures provide a systematic way of providing and removing prompts so that toddlers begin to perform skills independently. These procedures rely on reinforcing correct responses - both those that are prompted and those that are not. In addition to

Prompting procedures provide a way of systematically providing and removing prompts so that toddlers begin to perform skills independently. These procedures rely on reinforcing correct responses, both those that are prompted and those that are not. In addition to reinforcment, prompting procedures are often used in conjunction with other evidence-based practices including time delay and are an integral part of other evidence-based practices such as Pivotal Response Training and Naturalistic Intervention.

Three Components of Prompting

There are three main components in a prompting procedure:

-

the antecedent,

-

the behavior (target behavior or target skill), and

-

the consequence.

These three components are critical to implementing prompting procedures effectively. Each time a team uses these three components during an activity, it is called a trial.

The antecedent includes the target stimulus and the cue. The target stimulus is the “situation” in which we want the learner to perform the target skill. The target stimulus is important because it signals to the toddler that something is expected of him with or without direction from adults, therefore, helping the toddler make this connection and minimizing prompt dependency. The cue is a naturally occurring hint or task direction that tells the toddler the skills or behaviors they should be using.

When using prompting procedures, the cue should be consistent so that toddlers know exactly when they are supposed to do something. Toddlers are more likely to use a skill or behavior accurately when the cue and target stimulus are clear and consistent.

- discrete skills: single skills of a short duration (e.g., requesting objects, labeling pictures, social greetings)

- chained skills: a series of behaviors/ skills that include a number of steps put together to form a complex skill such as (e.g., dressing and undressing, washing hands, cleaning up a play area)

- response classes: groups of responses that have the same function.

Imitating adults or peers: a variety of behaviors could be used when imitating adults or peers, such as clapping, waving, driving a toy car, point to body parts, or imitating actions in simple social games; all of these behaviors make up the response class for the skill.

Initiating social interactions: a variety of behaviors could be used when initiating social interactions with others, such as speaking to a family member or peer, getting closer to a family member or peer, or offering a toy to a family member or peer; all of these behaviors make up the response class for this skill.

The reinforcement and feedback provided after a toddler’s response are critical components for teaching the target skill. When toddlers use skills successfully or respond accurately, feedback should be highly positive and descriptive so that toddlers know exactly what they did that was correct.

Positive feedback (reinforcement) increases the likelihood that the target skill will be used correctly in the future. With prompting procedures, correct responding should be reinforced even when it is prompted.

Feedback for incorrect responding, or incorrect use of target skill, is delivered either by ignoring the incorrect response or by applying a correction procedure (e.g. interrupting the toddler when they begin to respond incorrectly, repeating or stopping the trial, or completing the expected response).

Continue for Types of Prompts

Types of Prompts

|

Type of Prompt |

Description of Prompt Type |

|---|---|

|

A verbal prompt is any verbal assistance given that helps toddlers use target skills correctly such as spoken words, signs, or statements. A verbal prompt includes hints, a clue, or a direction and range in intensity level from least to most restrictive. For example, providing a direction is more restrictive than providing a hint about how to identify the object. |

|

|

A gestural prompt gives toddlers with ASD information about the cue to use a behavior or skill through the use of gestures. Gestural prompts may include pointing or touching an object (e.g. pointing to the car on the “road”). |

|

|

A physical prompt includes physically guiding or touching the toddler to help him/her use the target behavior or skill (e.g. tapping a toddler’s hand which is already on the toy car to cue him to push the car). Physical prompts are used when the toddler does not respond to less restrictive prompts (e.g., modeling, verbal, visual). Physical prompting is useful when teaching motor behaviors (Alberto & Troutman, 1999). |

|

|

The controlling prompt is the prompt that results in the toddler performing the skill correctly. It is the last prompt in a least to most prompt hierarchy. The controlling prompt can be any of the other types of prompts described above and is individualized for the toddler and skill. For graduated guidance, the controlling prompt is typically a physical prompt. |

|

|

A model prompt includes either performing the target skill for the toddler or showing the toddler what to do (e.g., pushing the car on the “road”). When using model prompts, adults demonstrate or model, the target skill. Modeling may be used to prompt discrete or chained skills (Alberto & Troutman, 1999). A model prompt is a component of modeling, another evidence-based practice. A description of model prompts is included here. For more information, please refer to the fact sheet on Modeling. |

|

|

A visual prompt includes pictures, photographs, or objects that provide the toddler with information about how to use the target skill or behavior (e.g., a washcloth or a picture of a washcloth as the cue to pick up the washcloth to wash face). Visual prompts are often incorporated into activities to help toddlers with ASD acquire target skills. For example, adults may show the toddler a photo or drawing with an example of a correctly completed Duplo structure. Visual prompts can be used to teach a wide variety of skills, including play activities and daily routines. When using visual prompts, it is important to identify supports that are developmentally and age appropriate for individual toddlers with ASD. For example, adults would not want to use pictures if the toddler does not yet have the ability to understand that a picture or drawing represents a real object. A visual prompt is a component of visual supports, another evidence-based practice. A description of visual prompts is included here. For more information, please refer to fact sheet on Visual Supports. |

A Note About Prompt Dependence

A Note About Prompt Dependence

If prompts are not used in a systematic manner (i.e. using a clear target stimulus, waiting for a response from the toddler before prompting, using them when they are not needed or not effectively fading the use of the prompts), toddlers can become prompt dependent. In other words, the toddler does not respond until the adult gives the prompt.

Learning to use a prompting procedure as intended should reduce the chance that toddlers become dependent on receiving a prompt before using the target skill or behavior.

Why Use Prompting?

Prompting, sometimes referred to as errorless learning, includes a set of procedures designed to reduce incorrect responding as toddlers acquire new skills. It is an effective way to help toddlers with ASD by maximizing their success and minimize the negative effects toddlers may experience when target skills are not used successfully (Kurt & Tekin-Iftar, 2008; Mueller, Palkovic, & Maynard, 2007; West & Billingsley, 2005).

This is particularly important for toddlers with ASD because they often have difficulty learning new skills through imitation and understanding the most important or relevant details of a task or skill. Prompting can be used effectively with toddlers, regardless of cognitive level and/or expressive communicative abilities.

The evidence-base shows that prompting is an effective intervention for learners with ASD throughout the age span of toddler to adults.

The evidence-base for prompting is covered in this Overview section.

Where Can Prompting Be Used and by Whom?

Any parent, family member, early interventionist, child care provider, or other team member can use prompting. Prompting procedures can be adapted for use in naturalistic settings such as during ongoing routines and activities in the home or in community-based settings.

EXAMPLE

Everyday skills or behaviors that are a part of a toddler’s daily activities and routines and that could be taught using prompting procedures include:

- requesting food during snack or meal times,

- requesting favorite toys or objects during a play routine,

- completing a play sequence, and

- completing a daily routine more independently such as getting dressed, brushing teeth or washing hands.

What Is the Evidence-base for Prompting?

![]()

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (NPDC) initially reviewed the research literature on evidence-based, focused intervention practices in 2008. A second, more comprehensive review was completed by NPDC in 2013.

- A total of 27 EBPs are identified in the current review.

- Of the 27 practices, 10 practices that met criteria had participants in the infant and toddler age group, thus showing effectiveness of the practice with infants and toddlers with ASD.

The practices were identified as evidence-based when at least two high quality group design studies, five single case design, or a combination of one group design and three single case designed studies showed that the practice was effective. The full report is available on the NPDC on ASD website.

Prompting meets the evidence-based practice criteria in all age groups (birth to twenty one) with 1 group design and 32 single case design studies. For the infant and toddler age group, one single-subject design study included toddlers with autism and demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting the development of pretend play behaviors (Barton, E. E. & Wolery, M., 2010). In addition, 14 studies included preschool children. Prompting procedures can be used effectively to address social, communication, behavior, joint attention, play, school-readiness, motor, adaptive, and, for older learners, academic and vocational skills. A complete list of the evidence base for children aged birth to five is included in the resource section.

Refer to the Prompting Fact Sheet from the updated EBP report for further information on the literature for prompting procedures.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What are some key reasons to use prompting?

Question:

What are the three components of a prompting procedure?

Question:

What are some different types of prompts?

Question:

Name and describe two prompting procedures?

Implementation Steps

After reviewing this section, you should be able to recognize the basic steps for this practice.

Least-to-Most Prompting

This prompting procedure is also referred to as the system of least prompts. With this procedure, a prompt hierarchy is used to teach toddlers with ASD new skills.

Levels of Least-to-Most Prompting Hierarchy

- The first level provides the toddler with the opportunity to respond without prompts.

- The remaining levels are sequenced from the least amount to the most amount of help.

- The final prompt is a controlling prompt that ensures that the toddler will complete the behavior or skill.

Least-to-Most Prompting is one of two prompting procedures included in this module. A variety of prompting procedures support the learning and development of toddlers with ASD.

Review information on both prompting procedures covered in this learning module and information on determining which prompting procedure is the most appropriate for an individual toddler and the type of target skills or behaviors you wish to teach.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

Step 1 for implementation of Least-to-Most Prompting involves planning the intervention. In this section, you will review steps for selecting a target behavior, identifying learning opportunities, choosing the cue or task direction for prompting, sequencing and fading prompts, and planning for data collection.

Step 1.1 Select the target behavior or skill

Select and describe the target behavior or target skill.

Beginning with the IFSP, the EI team discusses with the parent the strengths and challenges of the toddler in meeting a priority outcome and then describes the target skill. The IFSP outcome should be observable and measurable in order to be able to clearly describe the expected skill that the toddler will learn and how to determine when the toddler has mastered the skill.

EXAMPLE

Parents discuss with the providers that their toddler, Charlie, has few if any means of communicating his wants and needs. He uses unconventional ways to communicate what he wants such as going to the kitchen, standing in front of the refrigerator, and crying.The IFSP team initially writes the outcome in the following manner:

"Charlie will communicate his wants and needs by using another form of communication instead of crying."

Consider: Is the selected target skill or behavior described in observable and measurable terms?

The IFSP team initially had written Charlie's outcome in the following manner.

Initial outcome:

While this outcome describes the hopes and wishes of the parents, it is not written in an observable and measurable way.

The target skill is described as “communicate” by “not crying”. The activities and routines are not specified. This IFSP outcome can be re-written so that it is observable and measurable. To do this, the team will need to clearly describe the context (WHEN), the target skill the toddler will perform (WHAT) and how will we know Charlie has mastered this skill (HOW).

Re-written outcome:

The new outcome describes routines or activities with target skills that are observable and can be measured.

Step 1.1a Discrete or chained skill?

The next step is to determine if the target skill or behavior is a discrete or chained skill.

A discrete task or skill is a discrete task requires a single response. Discrete skills could be pointing to objects, naming objects, holding out a hand, or a task of putting objects in a container.

EXAMPLES OF DISCRETE TASKS

- pointing to or reaching for an object to request

- requesting an object verbally using the first sound in the word for the object

- pushing a truck on a “road” to a toy garage.

A chained task requires a number of individual behaviors which are chained or sequenced together to form a more complex skill.

EXAMPLES OF CHAINED TASKS

- washing hands

- brushing hair

- completing a sequence of a play scheme

Step 1.1b Decide on the number and sequence of steps

Decide on the number and sequence of steps in a chained task.

If the target behavior is a chained task or skill, decide on the number and sequence of steps in the chain.

You can decide on the number and sequence of steps in a chain in the following ways:

- Observe a typical toddler performing the chain. Write down the steps.

- Ask the parent to help their toddler perform the chain. Write down the steps.

- Perform the chain yourself. Write down the steps.

Use the steps you have identified as the sequence of steps in the chained task to teach the toddler.

EXAMPLE

A chained task for washing hands would include the following steps:

- Toddler climbs step stool to reach sink.

- Toddler opens hands over the sink so adult can pump soap onto hands

- Toddler rubs hands together.

- Adult turns on water and toddler puts hands under running water.

- Toddler gets paper towel.

- Toddler wipes hands on paper towel.

- Toddler throws away paper towel.

Video: Chained Task - Washing Hands

Video: Chained Task - Washing Hands

After each step in the chain has been described, decide:

Will you teach one step at a time?

Will you teach all the steps at the same time?

Step 1.2 Identify learning opportunities

Identify learning opportunities that will be the activities and routines to use with the toddler.

Select the activities and routines within which to teach the target skill. These activities and routines should be the learning opportunities that are naturally built into a toddler’s day.

- Using a toddler’s favorite activities will increase motivation through the use of natural reinforcers for the toddler.

- Using typical routines will allow the toddler to practice the target skills or behaviors frequently throughout the day.

Step 1.3 Identify the target stimulus

The target stimulus is the event or situation that cues the toddler to engage in the target behavior or target skill.

Target stimulus

Naturally occurring event

- If the target behavior is washing hands, then the target stimulus is having dirty hands or telling the toddler, “It is time for snack.”

- If the target behavior is waving "bye-bye," then the target stimulus would be a parent waving "bye-bye" to leave for work.

Completion of one event or activity

- If the target behavior is cleaning up after snack or a meal, then the target stimulus is completing the snack or meal.

External signal

- If the target behavior is coming to the table for a snack, then the target stimulus is opening the refrigerator.

- If the target behavior is getting ready to take a bath, then the target stimulus is turning on the faucet and running the water in the tub.

Step 1.4 Choose the cue or task direction

A cue or task direction is the “bridge” used to help the toddler identify the target stimulus and then engage in the target skill or behavior.

Choosing a Cue or Task Direction

The following types of cues may be selected depending on the skills of the individual toddler:

MATERIAL OR ENVIRONMENTAL MANIPULATION

Material or environmental manipulation can be used as cues or task direction by setting up the materials before the toddler comes to the activity. An example of environmental manipulation is when a EI provider or parent might place a toy on the rug prior to a play routine. Another example could be placing a small amount of a desired food on a plate in front of the toddler while placing a closed container with more of the desired food further away from the toddler.

TASK DIRECTION

A task direction is when you tell the toddler specific or giving the toddler a visual cue. For example, the EI provider or parent might say “All gone” or sign “All done” and then point to an empty bowl.

NATURALLY OCCURING EVENT

An example of a naturally occuring event is when a toddler sees a parent opening the cabinet to get food for snack, and then opening the refrigerator to get juice. Another example would be the parent turning on the faucet to fill up the bathtub.

EXAMPLE

A parent wants their toddler to ask for more cereal at breakfast table.

- The target stimulus is no more cereal in the toddler's bowl.

- The cue is saying, “All gone”

IIdentifying the Activity, Target Stimulus, Cue or Task Direction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Discrete skill: "Use one word utterance to request 3 favorite objects or food" |

|||

Word used: |

Activity (or Routine) |

Target Stimulus |

Cue or Task Direction |

|

“Truck” |

Play on floor |

Preferred toy out of reach (truck) |

“Let’s play.” |

|

“Boat” |

Bath Time |

Preferred toy out of reach (boat) |

“Time to play in tub.” |

|

“Apple” |

Snack |

Favorite snack out of reach (apple) |

“Snack all gone” |

Chained task as an activity: Washing hands prior to meals |

|

|---|---|

|

Target Stimulus: “First wash hands, then eat.” |

|

Chained Task Target Skill |

Cue or Task Direction |

|

Climbs steps of step stool |

Adult walks to the sink and says “Time to wash hands” |

|

Turns palms up |

Adult picks up soap dispenser, shows toddler and says, “Get soap” |

|

Rubs hands together |

Adult puts down soap dispenser and says “Rub hands” |

|

Puts hands under running water |

Adult turns on faucet and says “Rinse hands” |

|

Gets towel and rubs hands on towel to dry |

Adult turns off faucet and says “Dry hands” |

|

Throws towel in trash can |

Adult says “Put in trash” or “All Done” |

Step 1.5 Select reinforcers

Select reinforcers to pair with the target skill or behavior.

- highly motivating,

- naturally reinforcing, and

- tied to the activity or routine within which the target skill or behavior will be used by the toddler.

The goal of reinforcement is to increase the likelihood that the toddler will use the target skill again in the future. Positive reinforcement is generally the strategy that adults use first when trying to teach new skills or behaviors. Positive reinforcement refers to the presentation of a reinforcer after a toddler uses a target skill or behavior, therefore encouraging him/her to perform that behavior again in the future.

The toddler's deprivation state is when the toddler cannot have, or is deprived of, what he or she wants.

Positive reinforcers can be either primary or secondary.

Primary Reinforcers

Primary reinforcers are often naturally reinforcing to toddlers with ASD. These might include verbal praise, highly preferred activities, stickers, toys, or edibles.

Secondary Reinforcers

The value of secondary reinforcers must be learned by pairing primary reinforcers with other types of reinforcement. An example of a secondary reinforcer might be pairing the primary reinforcer using verbal praise, “You did it!” with a chance to play with a favorite toy.

Positive reinforcers include:

- access to a desired or preferred activity/favorite toy (e.g., special job, squishy ball, playing with cars, sand table) or social game (such as peek-a-boo or “so big”).

- specific verbal praise (e.g. “You put the block in!”).

- hugs or physical activity.

- access to the preferred food or drink

When choosing reinforcers, answer the following questions:

-

What has motivated the toddler in the past?

-

What does the toddler want that he/she can't easily get? This is called the toddler's deprivation state.

-

What reinforcer is appropriate for the target skill and routine or activity?

EXAMPLE

A toddler with ASD may continually request crackers that are placed in a cupboard or on a high shelf, however, the EI provider or parent only gives the toddler the crackers once a day.

Because the toddler wants the crackers, but cannot easily get them, this is considered his deprivation state.

The chosen reinforcer should be as natural as possible and it should be related to the activity that is going on. It would be natural for a toddler with ASD to have access to a preferred or desired activity/object after taking part in a challenging, non-preferred activity.

EXAMPLE

If the toddler does not enjoy washing his/her face, then a possible positive reinforcer to receive after completing the routine would be to select a highly desirable toy to give to the toddler once the activity is complete. Another example would be to use food as a reinforcer during routines such as snack or meal times when the target skill is requesting.

For more information on reinforcers, refer to ASD Toddler Initiative module on Reinforcement.

Step 1.6 Select the number of prompt levels

Select the number of prompt levels of the least-to-most hierarchy.

The number of levels of the least-to-most hierarchy depends on:

- the characteristics of the activity,

- the skill being taught, and

- the characteristics of the toddler.

A minimum of three levels is required. Prompts are individually determined, with a maximum of 3 levels. For example, pointing to the target stimulus (gestural prompt) and next modeling an action (model prompt).

There is no limit to how many levels can be used, but generally no more than five levels is practical.

Prompt Level |

Prompt |

Characteristics of the Level |

|---|---|---|

First |

Indpendent |

No prompts Target stimulus and cue are presented |

Intermediate |

Increasing help given and less help than the last level | Prompts are individually determined, with a maximum of 3 levels |

Most |

Controlling prompt | Prompt used is selected to ensure that the toddler will respond and perform the skill or behavior correctly |

Video: Prompting Hierarchy

Video: Prompting Hierarchy

![]() Tips on Determining the Number of Prompt Levels

Tips on Determining the Number of Prompt Levels

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LEARNING TASK OR ACTIVITY

With easy target skills, fewer levels are recommended. With more difficult skills, more levels may be necessary.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TODDLER

The more prompting levels in the hierarchy, the longer the toddler will have to wait to be successful. If the toddler with ASD has difficulty staying engaged in the activity or routine for a long period of time, then less prompting levels will increase attention and reduce the likelihood of disruptive or problem behaviors (e.g. crying, stereotypical or repetitive behaviors). If it is determined that the toddler needs more assistance to complete a target skill successfully, then more levels would be appropriate.

TIME AVAILABLE FOR USING PROMPTING IN THE ACTIVITY OR ROUTINE

In general, the more levels that are included in a prompting hierarchy, the longer the activity and fewer opportunities for working on the target skill.

Review prompt dependence in the EBP Overview.

Step 1.7 Select the type of prompts to be used at each level

Any number of prompts can be used in the hierarchy. EI providers and parents should consider individual characteristics when selecting prompts. For example, if the toddler does not like being touched or seeks touch, then a full physical prompt might not be a good choice. If a toddler can easily imitate, then model prompts might be appropriate; but if the toddler cannot imitate, then model prompts would not be the best choice.

Some common mistakes include:

- Using frequent verbal prompts.

- Too frequent use of physical prompts when less intense and intrusive prompts may be effective.

- Using prompts that are not appropriate for the individual toddler

Using a visual prompt of a lined drawing of an object when the toddler does not understand visual representation

Helpful Questions

Helpful Questions

-

Which types of prompts have been successful in teaching the toddler new skills?

-

Has the toddler been taught how to use this type of target skill before?

-

What types of prompts have been the most successful when teaching the toddler a variety of skills?

-

If this target skill has been successfully taught to others toddlers, what was the least-to-most sequence?

- Does the toddler use the target skill correctly when each prompt is used separately?

View the chart on types of prompts in the EBP Overview section of this module.

View the chart on types of prompts in the EBP Overview section of this module.Step 1.8 Sequence the prompts from least-to-most

When sequencing, determine which prompts provides the toddler with:

- the least amount of assistance,

- more information, and

- the most amount of assistance or enough to perform the skill or behavior correctly.

Sequence prompts from least-to-most, beginning with the independent level (least) and progressing to increased assistance (most) within the hierarchy.

You may want to ask the following questions:

a) Which types of prompts have been successful in teaching the toddler new skills?

b) Has the toddler been taught how to use this type of target skill before?

c) What types of prompts have been the most successful when teaching the toddler a variety of skills?

d) If this target skill has been successfully taught to others toddlers, what was the least-to-most sequence?

e) Does the toddler use the target skill correctly when each prompt is used separately?

(Wolery, Ault, & Doyle, 1992)

Step 1.9 Decide when to give the cue

The cue (or task direction) can be given:

- at the first prompt level.

- at each step of the prompt hierarchy. This is most appropriate when a toddler is first learning the skill.

Review two examples of prompt hierarchy with a given target stiumulus.

Example 1

Prompt Level |

Prompt |

Characteristics of the Level |

|---|---|---|

First |

Indpendent |

No prompts |

Intermediate |

First prompt Second prompt |

Gestural prompt: The adult holds up juice pitcher, shrugs shoulders, and raises eyebrows as if to say, “What do you want?” Verbal prompt: The adult says, “What do you want?” |

Most |

Model prompt | Model prompt: The adult says, “Juice.” Taylor says, “Juice.” Adult pours Taylor more juice. |

Example 2

Prompt Level |

Prompt |

Characteristics of the Level |

|---|---|---|

First |

Indpendent |

No prompts The adult says, "Wipe mouth." |

Intermediate |

First prompt Second prompt |

Gestural prompt: The adult points to the napkin on the table. Model prompt: The adult holds up the napkin and models wiping their mouth. |

Most |

Last prompt | Partial physical prompt: The adult moves the toddler's hand to the napkin and assists with bringing the napkin to his mouth. |

Step 1.10 Select the response interval

A response interval is the length of time to wait for the toddler to perform the skill or behavior before prompting the toddler to use the target skill. You should base the response interval on the individual characteristics of the toddler.

Generally a response interval is between 3 to 5 seconds.

The response interval is important because it builds in a short pause, allowing the toddler to process the cue and respond on their own to the specific prompt prior to the adult giving the toddler another prompt in the hierarchy. You will use this response interval at each prompting level.

Answering the following questions will help determine the length of the response interval for the toddler:

- How long does it take the toddler to complete a similar skill?

- How long does it usually take the toddler to respond when he/she knows how to do the skill? Add a couple of seconds to the usual response time.

- How long does it take another toddler with ASD to use a similar skill?

- What amount of time will the toddler be allowed to begin and complete an activity or routine? This would be important for a chained task or skill such as getting dressed, undressed, washing hands, etc. Some skills in the chain make take longer than the others. In that case, use the longest interval as the response interval.

Step 1.12 Plan a data collection strategy

You should develop your data collection strategy and decide on data collection forms to use prior to implementing least-to-most prompting.

At a minimum, data collected should include collecting information on the following:

unprompted correct responses

Correct response at the independent level of the hierarchy. This is the goal; thus, these responses should be reinforced and counted.

prompted correct responses

Any correct response that occurs after any of the prompt levels of the hierarchy. These responses should be reinforced and counted.

incorrect responses

These can be either unprompted errors - incorrect responses made at the independent level of the hierarchy (before any prompts are delivered), or prompted errors - incorrect responses made after any of the prompt levels of the hierarchy. For any incorrect response, you will be using a correction procedure.

no responses

Toddler does not make any response after the delivery of the last level in the hierarchy.

Step 1.13 Gather baseline data

Gather and record baseline data on the target skill(s). Information should be collected prior to beginning to use least to most prompting on the toddler’s ability to perform the target skill(s) (e.g. the baseline performance data).

A planning worksheet for prompting is available and included in the Module Resources section.

Practice Scenario: Planning Least-to-Most Prompting

The practice scenario will open as a PDF file  in a new browser tab/window.

in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

test prompting video for scenario

Knowledge Check

Question:

Consider the following target skill: Josh will complete a four piece wooden puzzle.

-

Is this a discrete or chained task?

-

Identify the target stimulus and cue.

-

How might you write the target skill so that the description is measurable and observable?

Question:

What are the three levels in a prompt heirarchy? Briefly describe each.

Question:

How do you determine the response interval?

Step 2 Implementing Least-to-Most Prompting

Using this prompting procedure requires following the steps outlined in the prompt hierarchy that was planned.

Step 2.1 Deliver the target stimulus and the cue

Present the target stimulus and the cue (or task direction).

- First get the toddler's attention.

- Then present the target stimulus and the cue.

EXAMPLE

Charlie is learning how to complete a clean-up routine. Charlie’s mom would first move close to Charlie and either stand in front of him at eye level or touching his arm. Then she would focus his attention to "all finished with eating." Charlie's mom would then hand Charlie the place and say, "Time to clean-up."

Charlie's mom secured Charlie's attention by standing in front of him at eye level or touching his arm.

Target stimulus: Charlie is all finished with eating.

Cue: Charlie's mom hands Charlie the plate and says, “time to clean-up.”

Step 2.2 Using the response interval, wait for the toddler to respond

Wait the number of seconds specified in the response interval. This is the time between delivering the cue and the prompt.

Parents can participate even in the early stages of using the prompting procedure by counting the number of seconds after the cue and then by signaling the EI provider to prompt if the toddler has not responded.

Step 2.3 Deliver prompts following the toddler's attempts

If the toddler's response is incorrect, provide positive feedback and the reinforcer to the toddler. This can be accomplished by interrupting the incorrect response, and then deliveriving the next prompt in the hierarchy. Also, deliver the controlling prompt last if toddler does not respond to the other levels of the hierarchy.

Use the response interval prior to delivering another prompt in the hierarchy.

Step 2.4 Fade prompts in the least-to-most hierarchy

As the toddler learns the target skill or behavior, you will need to implement the plan to fade prompts.

Review how to fade prompts in Step 1.11.

Tips for Effective Least-to-Most Prompting

When delivering prompts:

-

Prompts should be as weak as possible.

-

Unplanned prompts should be avoided.

-

Prompts should be faded as quickly as possible.

When fading prompts:

-

Use fewer levels of prompts. If a higher level of prompting is used, toddler may appear to be learning but may be dependent on the prompt not the cue.

-

Fading should be determined by monitoring toddler’s unprompted and prompted correct responses

-

Fade prompts and/or increase the response interval or wait time gradually and systematically.

-

Fade prompts as quickly as it is determined that toddler is responding without the prompts.

-

If prompts are not faded, prompt dependency can develop. Prompt dependency occurs as result of using prompts when not needed.

Practice Scenario: Using Least-to-Most Prompting

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What should you do after getting the toddler’s attention and providing the target stimulus and cue?

Question:

What strategies should you use if the toddler responds incorrectly to a prompt?

Question:

Describe some prompt fading strategies.

Step 3 Monitoring Progress

![]()

To monitor the effectiveness of least-to most-prompting, it is important to gather data and evaluate what types of responses are being made by the toddler.

Step 3.1 Schedule and record data

Schedule and record data on each type of response. Select a schedule for collecting and reviewing data for on-going monitoring. A schedule for collecting and reviewing the data should specify how frequently you will monitor (e.g. at each home visit, during each routine or activity on a daily basis).

Decide whether to record each trial during the activity or routine or to only record the last trial in the activity or routine.

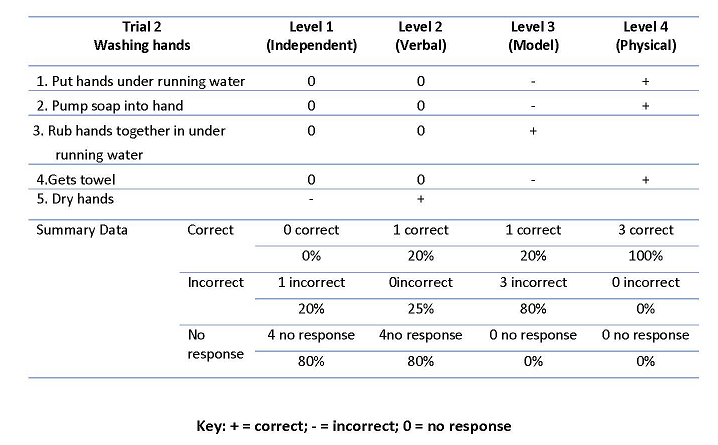

Record each type of response that occurs. A suggested response coding scheme is provided in the images below.

Download the Sample Data Collection Sheet from the Module Resources section.

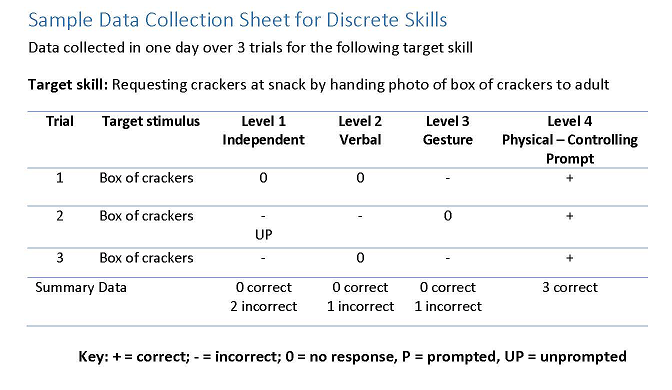

Step 3.1a Record data on four types of potential responses

Toddler responses to the prompts in using the target skills are not always successful. Therefore, the responses of the toddler can be thought of as correct (+) or incorrect (-), either with prompting or without prompting.

If the toddler completes the expected steps of washing hands without prompts, all responses would be coded as unprompted correct (+).

EI providers should track all of these responses because their occurrence provides valuable information about the toddler’s performance and progress. The data sheet should reflect each trial.

Review more about the four types of potential responses:

Step 3.2 Analyze the data

Analyze the data to determine if progress is being made.

Determine whether the unprompted and prompted correct responses total 100% of the toddler’s performance.

First, calculate the percentage of the unprompted correct, the percentage of the prompted correct, and the percentage of the incorrect responses. This should equal 100%.

Determine if the percentage of unprompted correct responses are increasing over time.

Next, review the data, based on your schedule of monitoring, to determine if the percentage of unprompted correct responses is increasing over time. If your target skill/behavior is a chained task, you will need to analyze each step of the chain.

Step 3.3 Use information from data

Use the data to modify, revise, or change the use of least-to-most prompting to enhance acquisition of the target skill or behavior.

Analysis of the data can help pinpoint problems in implementing the prompting procedure correctly or guide decisions about when the prompting procedure needs to be changed. Revisions or modifications to prompting might include:

- changing the type of controlling prompt needed,

- reducing the number of prompts within the hierarchy,

- changing the cue or response interval, and

- when to begin fading the prompts.

Based on the data and using the strategies on how to fade prompts that were discussed in the Step 1.11, remember to fade prompts in the hierarchy.

Common Problems and Solutions When Using Prompting

Problem |

Solution |

|

The toddler consistently makes errors at the final level in the hierarchy. |

Select a new, more controlling prompt |

|

The toddler consistently makes errors at an intermediate level. |

|

|

The toddler consistently waits for a prompt instead of attempting to respond at the independent level. |

Differentially reinforce prompted and unprompted correct responses or eliminate reinforcement for prompted correct responses |

|

The toddler consistently fails to respond at any level, including the final level. |

Find a more powerful reinforcer. |

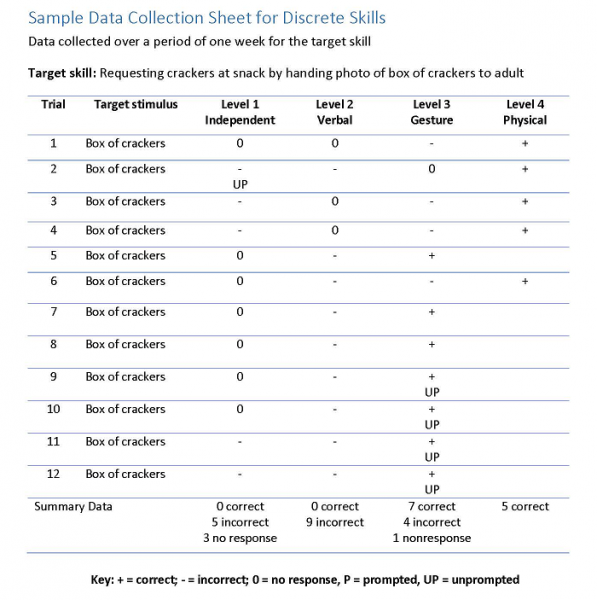

EXAMPLE

The EI provider continues to monitor progress of the toddler asking for crackers. She reviews data collected over a period of one week.

The data in the chart reflects that the controlling prompt has shifted from physical to gestural, given that the toddler is responding correctly at that intermediate prompting level.

A decision would be made to reduce the number of levels in the prompt, now only 3 levels.

Practice Scenario: Monitoring Least-to-Most Prompting

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What are the types of responses that should be collected when monitoring progress?

Question:

What can the data collected tell you about the effectiveness of the least-to-most prompting procedure?

Question:

What are some common mistakes that can occur when using least-to-most-prompting?

Graduated Guidance Prompting Procedure

With graduated guidance, practitioners provide a controlling prompt, a prompt that ensures the toddler will use the skill correctly, and then gradually remove the prompt during a learning activity or routine. This procedure differs from other prompting procedures because it requires practitioners to make judgments during the learning activity or routine about the type and amount of prompting to provide based upon the toddler’s response.

Graduated Guidance is one of two prompting procedures included in this module. A variety of prompting procedures support the learning and development of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Review information on both prompting procedures covered in this learning module and information on determining which prompting procedure is the most appropriate for an individual toddler and the type of target skills or behaviors you wish to teach.

Step 1 Planning

![]()

The first step for Graduated Guidance Prompting involves planning the intervention. Graduated Guidance requires many moment-to-moment decisions about when to apply and fade the prompts. As the toddler begins to acquire or use the skills, the prompts are faded (reduced and gradually withdrawn), but quickly reinstated if toddler regresses or stops using the skills. If the prompts are not faded appropriately, toddlers can become prompt dependent. Thus, using graduated guidance requires considerable skill.

Graduated guidance is used only with chained tasks or skills within an activity or routine that includes a physical component.

A chained task or routine requires a number of individual skills or behaviors which are sequenced together to form a more complex skill. With these types of skills, numerous steps comprise one completed task.

Step 1.1 Select and describe the target skills or behaviors

Select and describe the target skills or behaviors in the chained activity or routine.

a. Define the target skill or behavior in observable and measurable terms

Beginning with the IFSP, the EI team discusses with the parent the strengths and challenges of the toddler in meeting a priority outcome that includes a chained task or behavior. The IFSP outcome should be written in an observable and measurable way in order to be able to clearly describe the expected skill that the toddler will learn and how to determine when the toddler has mastered the skill.

The target skill is described as “complete self-care routines.”

This is not observable without a description of the actual self-care routine and what would be expected of the toddler. Furthermore, the activities and routines are not specified. The team will need to clearly describe WHEN will the target skill be performed, WHAT the actual skill or skills that the toddler will demonstrate, and HOW the EI team will know Charlie has mastered this skill.

The IFSP team re-writes the outcome so that it is observable and measurable using a WHEN, WHAT,and HOW format.

The re-written IFSP outcome: When Charlie has finished eating a meal or snack at the table (WHEN), Charlie will place his plate, cup and spoon on the counter and throw away his napkin to clear his place at the table (WHAT), 3 out of 4 opportunities for 4 out of 5 days (HOW the EI team will know).

The routines or activities are now described. The target skills are observable and can be measured.

b. Identify the number and sequence of steps in target skill or behaviors of the chain

This can be accomplished by using one of the following methods:

- using a sequence of steps from a curriculum;

- observing a typical toddler performing the chain and writing down the steps;

- asking the parent to help their toddler perform the chain and writing down the steps; or

- performing the chain yourself and writing down each step.

Video: Example of a Chained Task

Video: Example of a Chained Task

c. Decide if you will teach one step at a time or teach all the steps at the same time.

In most cases, teaching the chain in the sequence is preferred.

Step 1.2 Identify a specific activity or routine to teach

Since the target skills are always chained skills or behaviors, the selection of the activities, routines, and materials will be integrated into identifying the target skills or behaviors.

The target stimulus should signal the time for using the skill; therefore, teaching should occur when the chain is needed. Using typical routines will allow the toddler to practice the target skills/behaviors frequently throughout the day. The EI team would analyze the day and determine when and where the chained activity is needed. For some chained skills, natural times to teach the chain may be few, so it is important to build in times when the skill may be taught.

The target stimulus should signal the time for using the skill; therefore, teaching should occur when the chain is needed. Using typical routines will allow the toddler to practice the target skills/behaviors frequently throughout the day. The EI team would analyze the day and determine when and where the chained activity is needed. For some chained skills, natural times to teach the chain may be few, so it is important to build in times when the skill may be taught.

EXAMPLE

If you are teaching the toddler to develop a simple play scheme, you would want to identify one or two play opportunities in a day to teach the play skills.

Step 1.3 Identify the target stimulus

Clearly specifying the target stimulus allows the EI team member to be sure that the toddler is attending to the important cues that should, in turn, signal to the toddler that the chained routine or activity is about to begin. This will reduce the toddler’s dependence on an adult’s prompts, usually called prompt dependence.

Categories of target stimuli:

Naturally occurring event

If the target skill is a self-care routine, such as washing hands (because the toddler has been finger painting) then the target stimulus is having dirty hands.

Completing one event or activity

Referencing the example of Charlie completing a clean-up routine (Step 1.1), finishing a meal or snack would be the target stimulus for beginning the clean-up routine.

External signal

An external signal may serve as the target stimulus that could be something that an adult does.

Step 1.4 Select cues or task directions

Identify the event or object that will "cue" the toddler to perform the chained target skill or routine, or use the target behavior.

A cue or task direction is the “bridge” used to help the toddler:

- identify the target stimulus and

- then engage in the target skill or behavior.

The cue or task direction can be verbal or visual.

Material or environmental manipulation:

Materials are set up and ready before toddler begins the chained activity or routine.

If the chained activity is completing a four piece puzzle, the EI provider or parent would place the puzzle on the floor or table with the puzzle pieces placed next to the puzzle. This would signal to the toddler that he is to put the puzzle together.

Naturally occurring event:

These events signal the beginning of the chained skills, behaviors, or routine.

A parent turning on the faucet to fill up the bathtub would signal that it is time to take a bath.

As another example of a naturally occurring event, a child walking through the front door triggers the beginning of the “coming home routine” such as taking off shoes, coat, and washing hands.

Step 1.5 Select reinforcers

Select reinforcers that are appropriate for the individual toddler, the task demands, and the target skill or behaviors.

The goal of reinforcement is to increase the likelihood that the toddler will use the target skill again in the future.

Positive reinforcement refers to the presentation of a reinforcer after a toddler uses a target skill/behavior. Positive reinforcement is generally the strategy that adults use first when trying to teach new skills or behaviors. The reinforcers selected should be highly motivating.

Positive reinforcers can be either primary or secondary.

Primary reinforcers are often naturally reinforcing to toddlers with ASD. Some examples include: food, liquids, and comfort.

However, the value of secondary reinforcers must be learned by pairing primary reinforcers with other types of reinforcement. Some examples of secondary reinforcers include: verbal praise, highly preferred activities, stickers, toys, and edibles. An example of pairing is saying to a toddler, “You did it!” and then the toddler gets a chance to play with a toy. Reinforcers should be highly motivating, naturally reinforcing, and tied to the activity or routine within which the target skill or behavior will be used by the toddler.

With chained skills and the graduated guidance procedure, the completion of the chain is ideally a reinforcer; however, for many learners this is not the case. Thus, additional reinforcers should be used at the end of the chain if this is needed.

Some positive reinforcers include:

- access to a desired or preferred activity/favorite toy (e.g., special job, squishy ball, playing with cars, sand table) or social game (such as peek-a-boo or “so big”)

- specific verbal praise (e.g. “You put the block in!”)

- hugs or physical activity

- access to the preferred food or drink

When choosing reinforcers, the EI team answers the following questions:

- What has motivated the toddler in the past?

- What does the toddler want that he/she can't easily get? This is called the toddler’s deprivation state. For example, a toddler may continually request Goldfish crackers that are placed in a cupboard or on a high shelf; however, the EI provider or parent only gives the toddler the Goldfish crackers once a day. Because the toddler wants the Goldfish crackers, but cannot easily get them, this is considered his deprivation state.

- What reinforcer is appropriate for the target skill and routine or activity? The chosen reinforcer should be as natural as possible and it should be related to the chained routine or activity. For example, it would be natural for a toddler to have access to a preferred or desired activity/object (getting bubbles, listening to a favorite song) after taking part in a challenging activity (learning a play routine).

For more information about how to use positive reinforcement, please refer to the ASD Toddler Initiative module on Positive Reinforcement (ASD Toddler Initiative, 2013).

Step 1.6 Identify the controlling prompt

Identify the controlling prompt or a prompt that ensures that the toddler with ASD performs the target skill or behavior correctly. With the graduated guidance procedure, the controlling prompt is often physical. Controlling prompts should ensure that the toddler

performs the skill or behavior without prompting more than is necessary. Some skills may require more or less restrictive prompting.

For some toddlers the controlling prompt may be as simple as pointing to the faucet to prompt hand washing, while other toddlers may need full hand-over-hand assistance.

Further consideration must be made for toddlers who are not comfortable with touch, light, or heavy touch in particular; or being touched somewhere specific on their body.

EXAMPLE

Continuing with the example of Charlie learning the clean-up routine in Step 1.1A, the EI team decides that the controlling prompt will be hand-over-hand full physical prompt, which will ensure that he picks up the plate to start the clean-up routine.

Step 1.7 Determine the response interval

A response interval is the amount of time to wait after presenting the target stimulus, cue, and task direction before giving the prompt.

With graduated guidance, a short response interval (lasting a couple of seconds) occurs after the delivery of the target stimulus, attending cue, and task direction. As chains are being taught, the response interval is an opportunity for the toddler to start the chain on his/her own. Base the response interval on the individual characteristics of the toddler.

Generally a response interval is between 3 to 5 seconds.

- How long does it take the toddler to complete a similar skill?

- How long does it usually take the toddler to respond when he/she knows how to do the skill? Add a couple of seconds to the usual response time.

- How long does it take another toddler with ASD to use a similar skill?

- What amount of time will the toddler be allowed to begin and complete an activity or routine? This would be important for a chained task or skill such as getting dressed, undressed, washing hands, etc. Some skills in the chain make take longer than the others. In that case, use the longest interval as the response interval.

Step 1.8 Determine how to fade the controlling prompt

Strategies for fading prompts are part of the planning process and, as such, should be discussed prior to implementing the graduated guidance procedures.

As the toddler becomes more proficient at performing the chained skill, prompt fading strategies will be implemented quickly.

As the toddler becomes more proficient at performing the chained skill, prompt fading strategies will be implemented quickly.

Decisions about fading prompts are made during a trial or teaching session and require “thinking on your feet” about how to change the delivery of the controlling prompt. Consider the intensity or location of the prompt.

One error that is often made is using a more intrusive prompt in the moment when a less intrusive prompt would be as effective. For example. a full physical prompt may also be used when a partial physical might be just as effective.

Understanding how to fade prompts as you are using graduated guidance is critical in decreasing the likelihood that the toddler will become dependent. When the toddler needs the prompt before performing the behavior or skill this can result in prompt dependency.

Guidelines for Fading Prompts

- Fade prompts gradually, systematically, and as quickly as it is determined, through collection of data, that the toddler is responding without the prompts. Graduated guidance requires the adult to make decisions as the child is being prompted within the routine. Collecting data at each teaching moment or trial is necessary in order to effectively fade prompts.

- Increase the response interval gradually to determine if the toddler will respond independently.

- Decrease the intensity of the prompt quickly as you determine that the child is beginning to learn the skill or behavior. Intensity refers to the amount of pressure used when delivering the physical prompts. An example would be moving from complete hand-over-hand instruction to just having your hands on the learner while he or she does the chain.

- Provide less assistance by changing the location of the physical prompt. For example, if you have been providing a physical prompt by using a hand over hand, move the prompt further up the arm.

- Move to less intrusive prompts quickly and as soon as the toddler starts using the skill. Less is better.

- Immediately remove the prompt when it is no longer needed.

Step 1.9 Plan a data collection strategy

Develop a data collection strategy and data collection forms prior to implementing graduated guidance.

At a minimum, data collected should include:

- the steps of the chain that are completed without prompts,

- the steps of the chain that are completed correctly with prompts, including the intensity of each prompt, and

- the steps of the chain that are completed with resistance.

Step 1.10 Gather baseline data

Gather and record baseline data on each step in the chain.

Information on the toddler’s ability to perform each step of the chain (e.g. the baseline performance data) should be collected prior to beginning the use of graduated guidance.

A Graduated Guidance Planning Sheet may be used to record decisions made during planning.

Practice Scenario: Planning Graduated Guidance Prompting

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Knowledge Check

Question:

How do you determine the response interval?

Question:

Describe some considerations in identifying the controlling prompt.

Question:

Describe three considerations when fading prompts.

Step 2 Implementing Graduated Guidance Prompting

![]()

The initial steps involved with using or implementing graduated guidance prompting are: get the toddler’s attention; and present the target stimulus, and the cue or task direction.

Step 2.1 Get the toddler’s attention

Once you get the toddler's attention, present the target stimulus, and the cue or task direction.

Step 2.2 Wait for the toddler to respond

After delivering the cue or task direction, pause and wait for the length the response interval for the toddler to begin the chained task or activity or routine on his own. The controlling prompt is not given until the response interval is over. The only exception would be if the toddler makes an incorrect response (see Step 2.4).

EXAMPLE

Charlie’s mom says, “time to clean up” and gives him his plate. She then waits 3 to 5 seconds, the specified response interval, for Charlie to start moving toward the kitchen counter.

The task direction is "time to clean up."

Step 2.3 Provide the controlling prompt to initiate the chained task

If the toddler does not respond after a short response interval, use the controlling prompt. The adult provides the amount and type of prompt needed to get the toddler to start performing the chain. As soon as the toddler begins to do the chain, adults reduce the intensity or amount of the prompt and start to shadow the toddler’s movements.

Shadowing is a term used to describe the action of holding your hands near the toddler’s hands so you can immediately guide the toddler to complete the behavior.

EXAMPLE

For Charlie, the controlling prompt was identified as hand-over-hand from behind so that Charlie would begin the chain by taking his plate and placing on kitchen counter.

Video: Shadowing with a Toddler

Video: Shadowing with a Toddler

Step 2.4 Provide additional assistance if needed

Iif the toddler stops, responds incorrectly, or resists, provide additional assistance.

Review the following common challenges and solutions to graduated guidance:

Problem |

Possible Solution |

|

Toddler stops performing the chained step. |

The adult immediately provides the amount and type of prompt needed to get the movement started. |

|

Toddler begins to use the chained skill or behavior incorrectly. |

The adult immediately blocks that movement and provide the amount and type of prompt needed to get the toddler to do the chain correctly. |

|

Toddler resists the type of physical prompt. |

The adult should stop the movement and hold the toddler’s hands gently in place. When the resistance subsides, the adult assists the movement toward completing the step in chain again by applying the type of physical prompt needed. This may include reducing the intensity or location of the physical prompt. |

|

Toddler resists on the last step of the chain. |

The adult does not reinforce the toddler if there is resistance on the last step of the chain. This is to ensure that the toddler is reinforced for the correct behavior. Instead, the adult stops teaching the target skill/behavior until the toddler is no longer resistant. When the resistance subsides, the adult begins teaching the target skill/behavior from the beginning of the chain. |

|

Toddler consistently resists the prompt. |

Graduated Guidance many not be an appropriate approach for this skill or toddler. |

Step 2.5 Verbally praise and encourage the toddler as steps of the chain are completed

As the toddler correctly completes each step of the chain (prompted or unprompted), provide verbal praise and encouragement. At the end of the chain, provide reinforcement to the toddler for completing the task correctly.

Using Prompts with Graduated Guidance

Prompts should focus the toddler’s attention on the target stimulus, not distract from it.

When delivering prompts with Graduated Guidance:

-

Prompts should be as weak as possible.

-

Unplanned prompts should be avoided.

-

Prompts should be faded as quickly as possible.

-

The following are tips for fading prompts:

-

Fading should be determined by monitoring toddler’s unprompted and prompted correct responses

-

Reduce or fade prompts and/or increase the response interval or wait time gradually and systematically.

-

Reduce or fade prompts as quickly as it is determined that toddler is responding without the prompts.

-

If prompts are not faded, prompt dependency can develop. Prompt dependency occurs as result of using prompts when not needed.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What should adults do when they first begin to implement graduated guidance and teach the chained task?

Question:

Describe the key concepts of effective prompting.

Question:

After waiting for the toddler to respond (response interval) and giving the controlling prompt, the toddler initiates the chained activity, but stops.

How should the adult respond?

Question:

How should you respond when the toddler begins to incorrectly respond, use an incorrect behavior, or resists during the chain?

Practice Scenario: Using Graduated Guidance Prompting

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Practice Scenario files:

Center-based Scenario: Caleb in a Center-based Setting

Video: Graduated Guidance with Caleb

Video: Graduated Guidance with Caleb

Step 3 Monitoring progress

Monitoring progress for graduated guidance prompting involves:

collecting data, reviewing data, and analyzing data to determine if progress is being made.

Step 3.1 Gather and record data

Gather and record data on the types of prompts and the each type of the toddler’s responses. Each type of response could be correct, incorrect, or no response.

Gather and record data on the types of prompts and the each type of the toddler’s responses. Each type of response could be correct, incorrect, or no response.

An important component of graduated guidance is collecting data to monitor toddler outcomes. You will want to determine who collects the data. This could be the EI provider, parents, child care provider, etc.

When using graduated guidance, the EI team and family should measure at a minimum:

- the steps of the chain that are completed without prompts,

- the steps of the chain that are completed correctly with prompts, and

- the steps of the chain that are completed with resistance.

While not ideal, sometimes it is not possible to score each step of the chain. In such cases, the entire chain is scored as independent, prompted, or resistance. If prompts are given on any chain, it is scored as prompted. If resistance and prompts are given, it is scored as resistance. It would be important to record the intensity and location of the physical prompt.

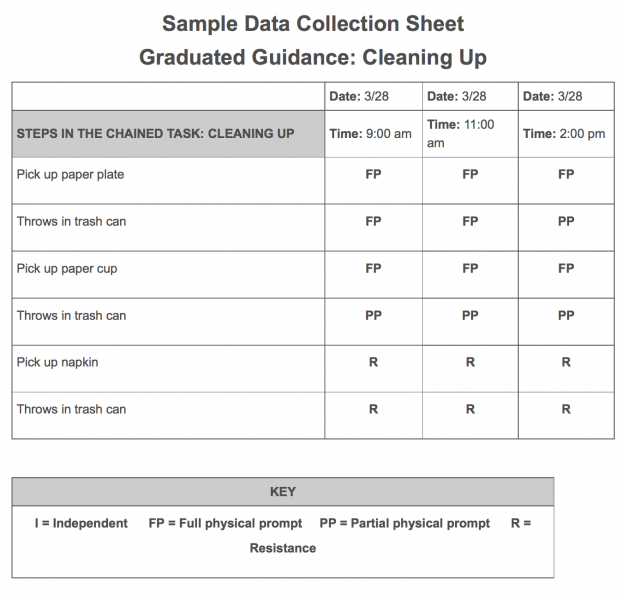

Sample Data Collection Sheet

Graduated Guidance: Cleaning Up

| Date: 3/28 | Date: 3/28 | Date: 3/28 | |||||

| STEPS IN THE CHAINED TASK: CLEANING UP | Time: 9:00 am | Time: 11:00 am | Time: 2:00 pm | ||||

|

Pick up paper plate |

FP |

FP |

FP |

||||

|

Throws in trash can |

FP |

FP |

PP |

||||

|

Pick up paper cup |

FP |

FP |

FP |

||||

|

Throws in trash can |

PP |

PP |

PP |

||||

|

Pick up napkin |

R |

R |

R |

||||

|

Throws in trash can |

R |

R |

R |

| KEY | ||||

|

I = Independent FP = Full physical prompt PP = Partial physical prompt R = Resistance |

||||

Step 3.2 Select a schedule for data review

Select a schedule for data review and on-going monitoring for prompting.

A schedule for reviewing the data collected will help determine how well the toddler is learning the steps of the chain and to make changes in the prompting procedure are made. This schedule could be every three days or once a week.

Determine which steps are still needing prompts. Then identiify the intensity and location of the prompts and determine the steps where the prompts should be systematically faded.

If a child is resisting during a step of the chain, a plan to determine how to deal with the resistance should be developed.

EXAMPLE

Reviewing the data from the data sheet example given for Cleaning Up in Step 3.1, the child is resisting on the last two steps of the chain. Asking questions about the way the prompt was delivered may clarify why this was happening. It would be appropriate to discuss the techniques for using the controlling prompt, whether the toddler needs more or less intensity, and how to handle resistance (e.g. and if resistance occurs, holding the toddler’s hands in place rather than forcing movement). Reviewing the information allows the team to review how to provide physical prompts (e.g. being careful not to force the toddler when physically prompting). If resistance continues, this may indicate that a different type of prompt or prompting procedure is appropriate.

Step 3.3 Analyze the data

Analyze the data to determine if progress is being made.

This includes which steps are completed without prompts and could, therefore, be either shadowed or independent.

Analysis of the data can help pinpoint problems in implementing the prompting procedure correctly or help make decisions about when the prompting procedure needs to be changed.

Modifications or revisions to the prompting procedure may include:

- changing the type of controlling prompt needed,

- changing the cue or response interval, and

- when to begin fading the prompts.

Data analysis can also help determine which steps are completed without prompts.

- Determine whether these steps are being shadowed or are independent.

- Determine which steps are being prompted, and the intensity and location of the prompts.

Based on the data and using the strategies on how to fade prompts that were discussed in the Step 1.8, remember to reduce intensity or location of the controlling prompt and fade the prompt.

Step 3.4 Use information from data to modify the use of prompting

Use information from data collected to modify, revise or change the use of graduated guidance to enhance acquisition of the target skill or behavior.

Analysis of data can be used to determine if the prompting procedure is being implemented correctly. If it is determined that the prompting procedure is not being implemented correclty, review the steps again for implementation in Step 2 Using Graduated Guidance.

- If the toddler is becoming more skilled in a step in the chain, begin to systematically fade the prompt. Information on how to fade prompts is discussed in Step 1.8.

- If a child is resisting during a step of the chain, develop and implement a plan on how to deal with the resistance.

EXAMPLE

The data from the sample data sheet in Step 3.1, Graduated Guidance: Cleaning Up, shows that the toddler is resisting on the last two steps of the chain.

Asking questions about the way the prompt was delivered may clarify why this was happening. It would be appropriate to discuss the techniques for using the controlling prompt, whether the toddler needs more or less intensity, and how to handle resistance.

In this example, if resistance occurs, hold the toddler’s hands in place rather than forcing movement.

Reviewing the information also allows the team to review how to provide physical prompts. This might include being careful not to force the toddler when physically prompting.

If resistance continues, this may indicate that a different type of prompt or prompting procedure is appropriate.

Knowledge Check

Question:

What basic data should be collected when using graduated guidance prompting?

Question:

What are the benefits to on-going monitoring of the graduated guidance prompting procedure?

Practice Scenario: Monitoring Graduated Guidance Prompting

The practice scenario will open in a new browser tab/window.

When you have finished reviewing,

return to the module and take the Knowledge Check.

Practice Scenarios

The practice scenarios provide example cases of using the EBP that follow the same toddler case through each of the implementation steps. After reviewing the practice scenarios, you should be able to answer questions about implementing this practice in home-based and center-based settings.

Practice Scenarios for Planning Prompting

Practice Scenarios for Using Prompting

Practice Scenarios for Monitoring Prompting

* This module contains two sets of Practice Scenarios for each of the prompting procedures covered.

Module Resources

View a description for each of the module resources

Implementation Checklist for Least-to-Most Prompting

Implementation Checklist for Least-to-Most Prompting

Implementation Checklist for Graduated Guidance Prompting

Implementation Checklist for Graduated Guidance Prompting

Parent & Practitioner Guide for Prompting (for both Least-to-Most and Graduated Guidance)

Parent & Practitioner Guide for Prompting (for both Least-to-Most and Graduated Guidance)

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

EBP Fact Sheet (an excerpt from the 2014 EBP Report)

Sample Data Sheets and Charts

Selecting a Prompting Procedure Chart

Selecting a Prompting Procedure Chart

Sample Data Collection Sheet for Discrete Skills

Sample Data Collection Sheet for Discrete Skills

Graduated Guidance Prompting Worksheet

Graduated Guidance Prompting Worksheet

References

Research Articles for the Birth to 3 Year Age Group

Barton, E. E., & Wolery, M. (2010). Training teachers to promote pretend play in young children with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 77(1), 85-106.

Research Articles for the 3 to 5 Year Age Group

Endicott, K., & Higbee, T. S. (2007). Contriving motivating operations to evoke mands for information in preschoolers with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(3), 210-217. doi: 10.1016/rasd.2006.10.003.

Fischer, J. L., Howard, J. S., Sparkman, C. R., & Moore, A. G. (2010). Establishing generalized syntactical responding in young children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(1), 76-88. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.009.

Koegel, R. L., Shirotova, L., & Koegel, L. K. (2009). Brief report: Using individualized orienting cues to facilitate first-word acquisition in non-responders with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 39(11), 1587-1592. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0765-9.

Leaf, J. B., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). Comparison of simultaneous prompting and no‐no prompting in two‐choice discrimination learning with children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(2), 215-228. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-215.

Reichle, J., Dropik, P. L., Alden-Anderson, E., & Haley, T. (2008). Teaching a young child with autism to request assistance conditionally: A preliminary study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 231. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/022).

Taylor, B. A., & Hoch, H. (2008). Teaching children with autism to respond to and initiate bids for joint attention. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(3), 377-391. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-377.

Thomas, B. R., Lafasakis, M., & Sturmey, P. (2010). The effects of prompting, fading, and differential reinforcement on vocal mands in non‐verbal preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Behavioral Interventions, 25(2), 157-168. doi: 10.1002/bin.300.

Twarek, M., Cihon, T., & Eshleman, J. (2010). The effects of fluent levels of Big 6+ 6 skill elements on functional motor skills with children with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 25(4), 275-293. doi: 10.1002/bin.317.

Williams, G., Donley, C. R., & Keller, J. W. (2000). Teaching children with autism to ask questions about hidden objects. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(4), 627-630. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-627.

Groskreutz, N. C., Groskreutz, M. P., & Higbee, T. S. (2011). Effects of varied levels of treatment integrity on appropriate toy manipulation in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1358-1369. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.018.

Ingvarsson, E. T., & Hollobaugh, T. (2011). A comparison of prompting tactics to establish intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(3), 659-664. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-659.

Ostryn, C., & Wolfe, P. S. (2011). Teaching children with autism to ask “what's that?” using a picture communication with vocal results. Infants & Young Children, 24(2), 174-192. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0b013e31820d95ff.

Vedora, J., Meunier, L., & Mackay, H. (2009). Teaching intraverbal behavior to children with autism: A comparison of textual and echoic prompts. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 25(1), 79.

Tarbox, J., Zuckerman, C. K., Bishop, M. R., Olive, M. L., & O'Hora, D. P. (2011). Rule-governed behavior: Teaching a preliminary repertoire of rule-following to children with autism. The Analysis of verbal behavior, 27(1), 125.

Ingvarsson, E. T., & Le, D. D. (2011). Further evaluation of prompting tactics for establishing intraverbal responding in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27(1), 75.